A copy of the Stele was placed right next to the "Christian Pagoda" of Daquin. And it is suggestive that in recent years hundreds of vocations of Catholic priests and nuns have flourished in the cities and mountain villages of the diocese of Zhouzhi, places linked to the arrival and beginnings of Christianity in China. The stele, built in 781 , represents (as stated in its heading -- the "Memorial of the Propagation of the Luminous Religion of Da Qin in China". In Chinese, the term Da Qin originally indicated only the Roman Empire. Then the expression was used to refer precisely to the communities of the Syriac Church that had permanently settled in China.

More than a thousand years later, scholars and academics from mainland China keep the spotlight on those beginnings of the Christian story in Chinese soil often forgotten, removed and unknown in Western academies. This was seen at the 2024 Xi'an International Jingjiao Forum, the 2024 international conference on the Syriac Church of the East (Jingjiao in Chinese) held from 5 to 7 July at the Shaanxi Hotel in Xi'an. A conference on Christian studiesThe 2024 Jingjiao Forum, entitled "New Orientations, New Historical Materials and New Discoveries", was organized by the Institute of Silk Road Studies of North West China University, and brought together more than 20 speakers from institutions in Mainland China, Macau and Italy. Priests from various Chinese dioceses (Xi'an, Shanghai, Beijing) also took part in the conference. Some reports took stock of the recent acquisitions of the archaeological campaigns carried out in the places where important garrisons of the Eastern Church stood on Chinese soil.

Related

Research that allows us to reconstruct the rhythms and practices of the daily life of those Christian communities gathered around the monasteries. The discovery in the sites of objects belonging to different eras -- underlined Liu Wensuo of Sun Yatsen University in his report dedicated to the excavations in the archaeological site of Turfan -- attests that the presence of seats and communities of the ancient Eastern Church in China has continued for hundreds of years. Other contributions of a historical, historiographical and theological-doctrinal nature have offered precious data and ideas for grasping the scope of that experience and the ways that allowed the fruitful encounter between that Christianity and China during the Tang dynasties (618 -907 AD) and Yuan (1272-1368 AD).

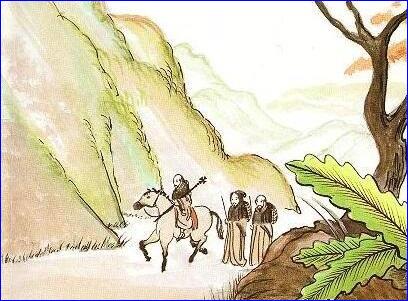

The monks of the Eastern Church, who arrived from Persia along the Silk Road -- underlined Professor Roberto Catalano, of the Sophia University Institute of Loppiano (Italy) -- were few , they did not follow a political agenda or "blueprint" to convert the Chinese Empire. Especially at the beginning, they practiced an "itinerant" style of proclamation similar to that of the first Apostles, presenting Christianity not as a "religion to be imposed" but as a "humble proposal", a gift to be offered in a plural and interreligious context. Their presence did not pose itself as an "antagonistic" force with respect to the social and political order: they asked and awaited the consent of the Emperor, whose portrait was displayed in churches to show everyone that they had received imperial authorization. Upon their arrival in China, in the work of explaining faith in Christ to other peoples, the monks assimilated terms taken from Buddhism, Taoism and classical Chinese sources.

In this way -- remarked Don Andrea Toniolo, Dean of the Theological Faculty of the Triveneto in his speech -- they attempted "a theological synthesis in Chinese with a language culturally different from that of Semitic or Greco-Roman origin". In these ways -- confirmed Professor Liu Guopeng, researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences -- a certain integration has been achieved in the field between the Christian faith and the language of Taoist thought. Even the veneration of the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus -- documented in his speech by Ding Ruizhong, of the Shaanxi Academy of Social Sciences -- was proposed with forms and accents familiar to the ancestral traditions of Chinese culture.

The adventure of the ancient Church of the East in China, described in the Xi'an stele, was very present to the Portuguese Jesuit Manuel Dias and his Italian brothers Giulio Aleni and Martino Martini, who in the 17th century were looking for new ways of meeting to announce the Gospel in society and in Chinese culture. The speakers Teresa Hou " to which to refer for every authentic "new beginning" of Christianity in Middle-earth. Even an authoritative group of Chinese scholars and academics has valorized the missionary adventure of Jingjiao as a historical experience in which the Christian communities, bearers of an announcement of salvation arrived from the Middle East, in the land of Confucius they were no longer perceived as expressions of a "foreign religion".

A recognition -- Professor Yin Xiaoping of the South China Agricultural University clarified in her report -- in which the scholars and researchers of Lingnan University especially distinguished themselves meritoriously, diligent in certifying that those communities had followed fruitful paths of adaptation to the context Chinese. Instead, the reading applied to the Jingjiao by historiography and journalism outside China has repeatedly appeared ambivalent. Starting from the mid-19th century -- as Paolo De Giovanni, professor at the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart of Milan, reported in his speech -- Western academic circles also questioned the authenticity and very existence of the Stele of Xi' an.

There was distrust for that historical find which shattered "the myth of a refractory and closed China", given that it attested to the work of Chinese emperors who became protectors of Christians. In the rereadings prevalent in missionary circles, especially evangelical and Protestant, the subsequent collapse of that network of monasteries and episcopal sees was branded as a historical failure, and the entire long history of the Eastern Church in China was traced back to the single figure of that failure, attributed by those circles precisely to the excessive mimetic attitude of that Church, which appeared to modern Western missionaries hesitant in proposing its own "identity" to the point of not differentiating itself from the followers of Buddhism or Taoism.

Even in those years, only a few oriental scholars offered a different and innovative point of view on the missionary adventure of the ancient Eastern Church: the Japanese Yoshiro Seki, in the book The Nestorian Monument in China, described that presence of bishops, monks and baptized people which continued for centuries in the territories of Persia, Mongolia and China as a "Christian civilization" in some ways similar to the one that was taking shape in Europe in those same centuries. The "disappeared" Eastern Church and "sinicization" The Conference of Xi'an concluded by confirming the opportunity to deepen studies and cultural exchanges around the historical story of the Eastern Church in China.

Chinese academics explicitly express the intention of studying and valorizing that encounter between Christianity and Chinese civilization which occurred long before the beginning of Western modernity. In that encounter, a community carrying the Christian message arrived in China not to impose itself as "import product". Through long and patient processes, the Christian experience was able to flourish by adapting to the cultural and socio-political context of the China of the Tang and Yang imperial dynasties. Today, the interest of Chinese scholars and academics in the events of the Eastern Church in China could offer interesting ideas also regarding the theme of the so-called "sinicization" that the Chinese apparatus requires of communities of believers. Comparison with the real dynamics of historical processes can always help clear away misunderstandings, rigorisms, mechanisms and ideological forcing.

or register to post a comment.