BY FOOT TO CHINA

Mission of The Church of the East, to 1400

By

John M. L. Young

Chairman

Japan Presbyterian Mission

Missionary of Mission to the

World of the Presbyterian Church in America

Assyrian International News Agency

Books Online

www.aina.org

Published 1984 A.D.

DEDICATED

to the memory of the men of God who thirteen centuries ago first took the gospel to China - "the missionaries who traveled on foot, sandals on their feet, a staff in their hands, a basket on their backs, and in the basket the Holy Scriptures and the cross. They went over deep rivers and high mountains, thousands of miles, and on the way, meeting many nations, they preached to them the gospel of Christ."

FROM AN ANCIENT TEXT.

AND DEDICATED

to one who "also serves" in a thousand ways with her faithful help - my wife.

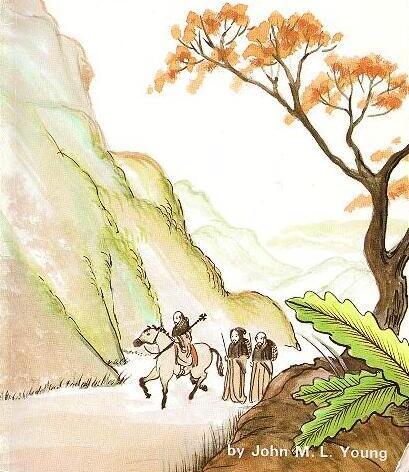

A restoration of the original silk painting of a missionary bishop of the Church of the East, now in the British Museum, London, discovered by Sir Aurel Stein at Tun-huang, western China, in 1908. It had been found, along with many manuscripts including some Christian ones, in a cave sealed in 1036. This restoration was painted by Robert MacGregor.

CONTENT

PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

PART I

THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE FIRST CHRISTIAN MISSION

TO CHINA

PART II

THE NESTORIAN CONTROVERSY

Nestorius' Christology

PART III

A gospel-preaching church with 1,300 years of missionary experience deserves our attention. It is the purpose of this book to focus on that great missionary effort. Only a part of the story, however, of the Church of the East's missionary enterprise, from the second century to the end of the fourteenth, can be told here. The main focus will be the mission to China during the last 800 years of that period.

Research materials for writing on this subject are available, although they are scattered over half the earth and are in various languages. Little, however, is written for the reader who is not pursuing advanced studies. English speaking Christians have been interested in the western expansion of Christianity--in history that involves their own origin and development - and little is accessible to them concerning the amazing missionary effort of the Church of the East. That the gospel of Christ's kingdom did confront the masses of Asia long ago, when the world's population was the densest there and civilization the most advanced, is today little appreciated by western Christians. How it fared in that confrontation is almost totally unknown.

The result is that when someone asks, "Where was the evangelical church of Christ during those long `Dark Ages' of Europe when the Church of Rome usurped the place of the Holy Spirit?" there usually follows a notable silence. The Iona colony of Scotland may be mentioned, or the later Waldenses of the Italian Alps, both involving small numbers. There is a better answer to the question, however, and the following narrative seeks to shed some light on it.

The story of the Church of the East's mission to Asia is one that needs to be told to today's church. It is the story of a dedicated missionary effort and the ever expanding witness of Christians from Antioch to Peking, nearly 6,000 miles by foot, until multitudes of Christians lived from the 30th to the 120th longitude in medieval times.

The facts and analyses that follow concerning the church's great epic of eastward advance, it is hoped, will bring encouragement, edification, and perhaps warning to our contemporary churches in their present mission to the unreached. Here is evidence that God gives strength and conversions in the direst and seemingly most impossible circumstances.

Here also is evidence that pitfalls to the church's mission always exist. Common examples are such things as an inadequate appreciation of the spiritual deadness of the natural man, failure to recognize the necessity of heart repentance and the meaning of baptism, the temptation to consider external acts of piety as necessarily representing inner holiness, the acceptance of liturgy and form in the place of justification by faith alone and identification with Christ, compromise with the world's secularism and other people's religious practices, sacramentalism, over-identification with a particular political regime, and concern with the elite that leads to failure to reach out to the common people.

As troublesome a problem as any, however, to those desiring to bring the gospel by word and deed into a foreign culture, deeply concerned to make the love and salvation of Christ understood, is the difficulty of adequately contextualizing the gospel without compromising its true meaning and uniqueness. The contextualization takes place not necessarily when the missionary succeeds in crossing the barriers of culture and language, so as to enable the listener to feel he understands the westerner's gospel, but when this new understanding is genuinely reflective of the New Testament message of Christ's redemptive love and mercy and involves a heart commitment to Him.

The lesson of the gospel in the Near and Far East during the Middle Ages is that such failures as are referred to above can cause Christian communities where churches once flourished to disappear so completely that later generations not only do not know what the gospel is but are not even aware that it was ever present in their midst. In those cases the only witness to the living may be the testimony of the dead, written on tombstones. An illustration of such a voice out of the past is that of a ninth century Christian in a central Asian cemetery, where the gentle words still whisper, "This is the grave of Pasak - The aim of life is Jesus, our Redeemer."

The lessons of history need to be studied for, as one sage noted, "Those who do not learn from the past are doomed to repeat its failures in the future."

In the year 635 A.D., a party of foreigners from the distant West, a vague area known to the Chinese for many centuries as Ta Chinn, reached the capital city of the Great Chinese Empire, Ch'ang-An, later called Hsian-fu. It was in the early years of the T'ang dynasty.

They indicated that theirs was a religious mission to bring to the empire knowledge of the doctrines and salvation of Jesus Messiah. The emperor gave them permission to practice their religion which he officially named the Ta Ch'in Chiao, the Ta Chinn religion. They themselves used the name Ching Chiao, Luminous Religion (or Illuminating?), and referred to their home church as The Church of the East. The Church of Rome, however, called them "Nestorians," and its thirteenth-century envoys and missionaries to the Far East always referred to the churches of these early missionaries from "The Church of the East" as "Nestorian" churches.1

Who were these early missionaries? Where did they come from? Were they holders of the "Nestorian" doctrine condemned as heresy at the Council of Ephesus in 431? Did Nestorius himself hold it, and what was their attitude toward him? What do the nine Chinese and two Syriac manuscripts, discovered in north China this century, and the famous "Nestorian" monument inscription, discovered in 1625 by Jesuit missionaries near Ch'ang-An, reveal about their mission, theology, and particularly their christology? Was there anything unique in their theology or christology which motivated this great missionary zeal? And why did this tremendous missionary effort end in failure? These are questions which need investigation and which are pursued in the following chapters.

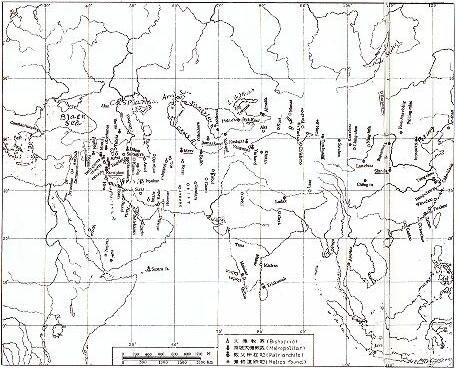

Part I traces the main details of the eastward expansion of the gospel from Antioch to Syria, across Persia and Mongolia, and on into north China by the ancient trade routes, noting the evidence of the Christian missions' activity.

Part II examines the christological controversy of the fifth century to ascertain what the church understood "Nestorianism" to be and what Nestorius's own presentation was, in order to come to an understanding of the theology of Nestorius and "Nestorianism." Those not desiring to follow the christological study of chapter six, with its linguistic considerations, may find the conclusion at the end of the chapter an adequate summary.

Part III examines the ten Chinese and two Syriac documents found in north China, considered to have been written by Christian missionaries between the seventh and eleventh centuries, to learn in what sense these missionaries were "Nestorians," and what relation, if any, this connection had to their missionary zeal and subsequent failure.

Much of the material of the latter two parts was prepared during studies at Calvin Theological Seminary when writing on the theme, "The Theology of the Nestorian Missionaries in China from 600-1000 A.D.," for a master of theology dissertation. The writer is much indebted to the very able assistance of Dr. Fred Klooster, professor of systematic theology at that institution, under whose direction the paper was written.

We shall begin, then, by tracing the history of the expansion of the Christian church eastward and the entrance of its missionaries into China.

CHRONOLOGICAL GUIDE

| A.D. | |

|

35 |

A tradition arose that the apostle Thomas Preached in the Kingdom of Osrohene of Armenia (upper Euphrates) on his way to India. |

|

100 |

A congregation existed in Edessa, considered to be the first of the Church of the East. |

|

180 |

Tatian's Diatesseron completed. |

|

200 |

The Church of the Eat in Edessa had a bishop and a theological college. |

|

258 |

Djondishapur founded on the lower Tigris with much Christian participation. |

|

280 |

Bishop of Selucia-Ctesiphon on the lower Tigris made first Catholicus. |

|

301 |

Kingdom of Osrohene declared to be a Christian state, the first in history. |

|

325 |

Council of Nicaea held and a theological college founded at Nisibis. |

|

350 |

Syriac New Testament (Peshitta) Produced. |

|

400 |

Jerome's Vulgate, a Latin version of the New Testament, produced. |

|

424 |

The Church of the East appointed its own patriarch and declared him to be their highest court of appeal. |

|

428 |

Nestorius called from the Antioch seminary to be the emperor's chaplain at Constantinople. |

|

431 |

The Council of Ephesus met to accuse Nestorius of holding a two-person christology and in his absence declared him to be a heretic. |

|

433 |

Formula of Union between the patriarchates of Antioch and Alexandria affirmed. |

|

451 |

Council of Chalcedon held. |

|

484 |

The Synod of Beth Lapat (lower Mesopotamia) declared the Church the East independent of the Western Church of Constantinople and Rome. |

|

488 |

Emperor Zeno demolished the Edessa theological college and the hospital was abandoned. The tradition of both was continued at Djondishapur. |

|

499 |

The Synod of the Church of the East rejected celibacy of the clergy. |

| |

|

|

503 |

A bishop's seat was established in Samarkand and a linguistic school at Merv, for preparing written languages for the central Asian tribes, for Scripture translation. |

|

600 |

Printing of full-page texts from carved wood-blocks was underway in China. A horoscope of later times set the birth of Krishna at this date. |

| 618-907 | The period of the T'ang Dynasty of China. |

|

622 |

Mohammed's Hegira to Medina and the origin of the Muslim religion. |

|

635 |

Christian missionaries reached Ch'ang An, capital of China. |

| 635-643 | Metropolitans appointed to Samarand India, and China. |

|

641 |

The first Christian manuscript written in Chinese presented to the emperor. |

| ?17 | The second group of Christian missionaries arrived in Ch'ang An. |

|

720 |

Shih t'ung (On History) first full study of historiography written. |

| 724-748 | The visit of a Persian Christian physician to the Japanese emperor and probable conversion of the empress. |

|

751 |

The defeat of Chinese troops west of the T'ien Shan mountains by Arabs. |

|

781 |

The Nestorian monument erected in Ch'ang An. |

|

782 |

Prajna, Indian Buddhist monk, arrived in Ch'ang An with manuscripts to translate into Chinese. |

|

800 |

Charlemagne crowned emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. |

| 801-806 | Kobo Daishi and Dengyo Daishi from Japan studied Buddhism in Ch'ang An, near the Christian church there, returning to Japan to establish new, esoteric forms of Buddhism. |

|

845 |

An edict drastically reducing Buddhism, Christianity, and other foreign religions in China was promulgated. |

| 858-1342 | A cemetery with tombstone dates and crosses, discovered in Turkistan a century ago, was in use during this period. |

| 947-1125 | The Liao of Manchuria established their dynasty over north China. |

|

1001 |

The first Muslim invasion of India occurred. |

|

1007 |

The conversion to Christianity of large numbers of Keraits took place. |

|

1036 |

A Tun-huang cliff-cave was sealed containing some 2,000 Buddhist manuscripts, a few Christian ones, and some Christian paintings. |

|

1060 |

The earlier Chinese invention of gunpowder was developed for cannon warfare and military flamethrowers, water clocks, and the magnetic needle in a compass (for sea navigation) were Produced in this century. |

| 1124-1234 | The Chin Dynasty ruled over north China from the capital of Yen Ching near Peking. |

|

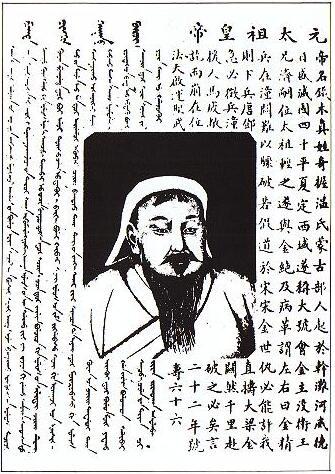

1167 |

Te-muchin (Genghis Khan) was born east of Karakorum. |

|

1211 |

The Mongols conquered the Chin of north China. |

|

1220 |

The Mongols defeated the Muslim army of Persia. |

|

1227 |

Genghis Khan died. |

| 1229-1241 | Ogodai ruled as the Great Khan. |

|

1241 |

The Mongols withdrew their conquering armies from Austria, near Vienna, because of Ogodai's death. |

|

1245 |

John of Plano Carpini arrived at Karakorum in time to witness Guyuk's election to be the Great Khan (1245-48). (Guyuk was said to be a Christian.) |

| 1251-59 | Mangu ruled as the Great Khan. |

|

1253 |

William of Rubruck arrived at Mangu's court, an envoy from the King of France. |

| 1260-1294 | Kubilay Khan became the founder of the Yuan Dynasty of China. |

|

1266 |

Kubilay requested the two Polo brothers to bring back from Rome one hundred Christian scholars. |

|

1271 |

The crusade of Edward I of England failed to recapture Jerusalem, in spite of token Mongol help. |

|

1274 |

The Act of Union between the Western and Eastern Churches was adopted at the Council of Lyons. |

| 1275-1292 | Marco Polo visited Peking and traveled in China. |

|

1278 |

Two Oriental monks left Peking to visit the patriarch at Bagdad, one becoming the next patriarch. |

|

1281 |

The Mongols invaded Japan and were defeated. |

|

1291 |

Argun Il Khan (a Christian) wrote to the king of France a proposal for a joint war on the Muslims of Egypt, but died shortly after writing. |

|

1369 |

The Ming Dynasty took over China and proscribed Christianity. |

| 1370-1405 | Tamerlane, Khan of the Middle East, destroyed many cities and slaughtered great numbers of Christians in his Muslim Holy War. |

By the year 800 there were more Christians east of Damascus than there were west of that city. This statement may seem astonishing, if not incredible, to the average Western reader who knows almost nothing about Eastern church history. Students of the early growth and spread of Christianity in the Eastern lands, however, will recognize it not only as entirely factual but also as only one of many facts testifying to the remarkable missionary zeal of the eastward bound Christians.

It all began with the fulfillment at Pentecost of Christ's promise of an outpouring of His Holy Spirit for the empowering of a witness to Him throughout the world in the new international age of the gospel. "Parthians and Medes and Elamites, and residents of Mesopotamia"2 were there, their lives set ablaze with a new dedication to return to their homelands to proclaim the good news that Messiah had truly come for man's eternal salvation. The planting of the church in Antioch was an immediate result. The New Testament presents something of the history and significance of that church's missionary effort in its westward movement. But history records also an eastward expansion of the gospel with churches planted in Damascus, Edessa and Mesopotamia, in Media, Elam and Parthia (the later Sassanian empire of Persia) and in India. The church resulting from all this Eastern missionary activity came to call itself the Church of the East.

The Church of the East, considering itself distinct from the Western (Roman) or Eastern (Byzantian) Churches, holds its origin to have been in Edessa, modern Urfa of Turkey, the capital city of the little Kingdom of Osrohene in northern Mesopotamia (between the rivers). Their tradition claims that King Abgar, son of Na'na, on hearing of Christ and His remarkable miracles, wrote to Him inviting Him to come to minister to his people. Our Lord received the message, so the story goes, shortly before His crucifixion, so Thomas undertook to send Addai (Thaddeus) one of the seventy who had been sent out to evangelize. From this disciple's ministry the gospel was planted in Edessa, considered the first Church of the East, its eastward expansion beginning from that city.3

Whether one accepts this story or not, we do know that there was a church in Edessa early in the second century and that the bishops of Edessa traced their succession to Serapion, Bishop of Antioch from 190 to 203.4 Also the coins of Edessa from 180-192 show a cross on the king's headgear. There is a Syrian tradition, however, that the apostle Thomas was their first patriarch. In a book called Eclesiastike, purporting to contain the preaching of the apostles, the writer, Bar Aurai, maintains that the apostle Thomas preached Christ in the East in the second year after His ascension. Thomas was on his way to India, he 'states, and "We have reason to believe it true, what the Syrian writers sand fathers say, that they regard St. Thomas to be their first patriarch, and accordingly they called themselves St. Thomas Christians."5 The Mar Thoma Church of south India holds to this day that Thomas came to them to preach the gospel and to found their church.

It is in the early literature of the Syrian church, however, that we see most clearly its antiquity and independent nature. Their language was the Aramaic, considered by many to be the language of our Lord, but in the eastern dialect of Edessa, while the written language was the old Syriac, Biblical Aramaic (Chaldee).6 Tatian, born in Edessa, in 150, composed a gospel harmony in continuous narrative form, called the Diatesseron, which for well over a century was the only gospel known by Persian Christians. About 350 a Syriac New Testament, the Peshitta (simple) appeared--but Burkitt claims that it was not a new translation, only a revision of an Old Syriac ones.7

The Syriac Old Testament, Burkitt holds, is even older than the name Peshitta. It is quoted both by Aphraates (337 A.D.) and in the Acts of Thomas (first century), he contends. Specifically he states, "The Peshitta is a direct translation from the Hebrew, in all essentials, from the Messoretic text."8 Such a translation was inevitable, he feels, both because Edessa's independent civilization would require a vernacular version and because the Jewish converts in the church would insist on a translation from the Hebrew.

Although Burkitt places the Creed of Aphraates at about 337, he holds that the Acts of Thomas was written by Judas Thomas himself, the brother of our Lord. His comment on this is most interesting. "I believe most firmly that it was originally composed in Syriac, not Greek ... a doctrinal work cast in narrative form ... it is as truly a book of religious philosophy as the Pilgrim's Progress, and it demands from us serious study."9 Thus he would give strong support to the early origin and independent nature of the church in Edessa.

Edessa--the capital of the small kingdom of Osrohene, lying between the outer edges of the two great empires of Rome and Parthia--sometimes a tributary of Rome (116 A.D.) and sometimes under the suzerainty of Parthia--became a Roman military colony in 216. The Sassanian dynasty of Persia, farther south, conquered Parthia in 226 and throughout that century was at intermittent war with Rome. In 258, the Sassanian king, Shopur I, captured Antioch and brought many learned scholars and doctors, among whom were Christians, back to Beth Lapat of Khuzistan, near Susa. Here they were ordered by the king to build a new city, Djondishapur, the future Eastern cultural, academic and medical center of learning. It was here that many of the east bound missionaries received their training in theology and medical lore. Later some of them were to testify that like Abraham they had left the land of Ur to bear witness for God.

The Romans recovered their losses and finally in 303 signed a treaty of peace with the Persians making the Abaros River, a tributary of the Euphrates, the boundary between the two empires. The Roman backed king, Terdat, had been restored to the throne of the Osrohene Kingdom of Lesser Armenia, a small country of northern Mesopotamia, and in 301 he declared his kingdom a Christian state, the first in history, with Gregory the Illuminator as the Church's head. After King Terdat embraced the gospel his people became Christians. With the death of Constantine in 327 and of Terdat in 342, however, the Persian king launched an attack to regain the lost western territories. The Christians of Armenia were identified with the Roman enemy, whose emperors were now Christian, and violent persecution was carried out against them, including the burning of their churches.

The Persian Zoroastrian priests were greatly concerned at the headway the Christians were making under the toleration of the treaty conditions. They finally succeeded in stirring their king to pass discriminatory laws against the Christians, which led to a renewal of persecution, on the grounds the Christians were friends of the Romans, sharing the sentiments of their enemy Caesar. Many Christians chose to flee the country at this time, some going to Nisibus (under Rome) where a theological college had been begun in 326 by a bishop just returned from the Nicene Council. In 363, however, Nisibis was recaptured by the Persians and the college fled to Edessa. In 399, a more tolerant Persian king, Yezdegerd I, came to the throne and the Romans again sought peace by sending an embassy seeking a treaty. An edict of toleration was signed in 409 giving toleration to Christians in the Persian Empire and the same to Zoroastrians in the Roman Empire.

The next year a synod was called for the whole area. It met in Selucia-Ctesiphon, on the lower Tigris, with some 40 bishops present, and was under the leadership of that city's chief bishop, who had the title of Catholicos. They adopted the Nicene Creed and defined the boundaries of some of the sees. A new and special title was given to the catholicos of "Grand Metropolitan and Head of all Bishops."

With the death of the peace-minded Yezdegerd I in 420, persecution of Christians broke out again and for many of the same reasons as before. Warfare with Rome also was renewed on the frontier but peace was concluded in 422. The immediate effect on the churches of the Armenian-Mesopotamian area was to convince them that they must by all means disassociate themselves from the Roman Church's jurisdiction (they were under the patriarch of Antioch) to escape future persecutions for political reasons.

In 424 another Council was called, this time at Markabta, with six metropolitans and 31 bishops attending. They declared their independence from the patriarch of Antioch and made their own Catholicos their new patriarch. They further agreed "that no appeal should be made from his decrees to 'western patriarchs'."10 Although no doctrinal difference was declared to exist between the Church of the East and Rome, the Council did proclaim its Church to be independent in government and, in the words of Wigram, "it did as much as a Council could do to set an Oriental papacy over itself."11 It was the first major crack in the structure of the Christian Church's organizational unity.

In the next act of separation from the Western church, however, doctrine was involved. The sympathies of the Eastern churches were with the Antiochene theology as we shall see later. Many of the leaders of their churches and of their theological college in Edessa, as well as the founders of the school of theology in Djondishapur, had been trained at the Antiochene theological seminary. Thus they opposed the decision of the Ephesus Council of 431 and supported the deposed Nestorius. The christological controversy raged in the Edessa theological college itself for many years until in 488 the Roman Emperor Zeno closed the college, had it torn down and on the site erected a church dedicated to Mary with the controversial title theotokos.12 Most of the students and faculty moved east to Nisibis to reopen a theological school there, one which eventually became very large and influential.

Prior to Emperor Zeno's closing of the Edessa "Nestorian" work in 488, a very significant event in the history of the Church of the East took place in Beth Lapat, near the ancient Ur of the Chaldees. An important theological event had just occurred in the West. Zeno had addressed his famous Henotican (instrument of union) to the patriarchs of Constantinople, Alexandria and Antioch, and all three had adopted his formulation of the heretical monophysite christology. In 484 the Church of the East called a synod to meet in Beth Lapat to adopt what Rome called a "Nestorian" confession, in response to the Increasing monophysite takeover. They did not oppose the Chalcedonian formula of 451, but resented that Council's confirmation of the repudiation of Nestorius. Within the churches east of Antioch, by then, there were three distinct parties centering around each's particular christology, and each had its scholarly defenders. 1) There were the followers of Cyril of Alexandria's doctrine that Christ had two natures, one divine and one human, in one person.13 (Most of the monks of his see, however, held that the human nature was divinized by the logos and therefore, to all intents and purposes, did not exist after the hypostatic union.) 2) The Church of the East was most amenable to Nestorius's doctrine that Christ had two natures and two kenume (the set of personal characteristics of each nature) in one person. 3) The followers of the doctrine of Eutyches of Alexandria, however, held a view that was gaining increasing support in the east, the monophysite heresy that Christ had only a divine nature in His person after the ascension, the human nature having been divinized.

By the time of the Beth Lapat synod, the churches of Edessa and Upper Mesopotamia had been captured by the monophysite heresy. To make a sharp break with this error of the upper Mesopotamian churches, which were still considered a part of the western church, and to escape further controversy over the christological formulation, the synod decided to separate the Eastern church not only from the Western church's ecclesiastical jurisdiction (as in 424) but from its doctrinal confession as well, particularly with regard to its adoption of the Alexandrian monophysite heresy. Thereafter they considered themselves to be a different church, the Church of the East. The crack had widened into a complete break.

From then on not only in practice but in fact there were two independent Christian churches in the world, each with its own government and doctrinal position. It was not that the Roman Church and the Byzantian Church held the same christology, for Rome was duophysite and the Byzantian eastern churches had become monophysite. But they were still one church, the Western, Roman Church. The Church of the East too was duophysite, with a slightly different way of expressing it, but definitely not holding the view condemned at Ephesus as "Nestorian" (making Christ appear to be two persons), as we shall see later. But the Church of the East no longer considered itself a part of the Roman Church, and the Roman church retaliated by labeling it "Nestorian" after the deposed "heretic," Nestorius.14 In 499 another synod of the Church of the East rejected the doctrine of the celibacy of the clergy (though a later act required the highest clergy to be celibate, a rule sometimes ignored in different times and places). This rejection of the highly honored Roman rule made the Church of the East even more disdained by the Roman clergy.

These Eastern or "Nestorian" Christians were versatile and diligent propagators of their faith. With the flight of the Edessa theological school to Nisibis, outside the farthest borders of the Roman Empire, and the opening of another in Djondishpur, with a hospital also in the latter city, many Syrian Christians began to move eastward into Persia and to revive the spirits of that harassed Church. Zernov writes that "The Nestorians were renowned doctors. Some of them exercised considerable political influence, being confidants and advisers of such Califs as Harum al Rashid (785-809) and his successors. The third center of Christian scholarship was Merv, where many translations were made from Greek and Syriac into languages spoken in Samarkand and Bokhara."15

The influence these centers of learning had on the Arabs was also very great. Schaff, in a very interesting footnote, states his wonder that the "Nestorians" should have had such an important influence on the geographical extension of knowledge, even on the Arabs before they reached the learned Alexandria. They received their first knowledge of Greek literature through the Syrians, he wrote, and learned of medicine through the Greek physicians and those of the "Nestorians" at Edessa. Then he adds, "Feeble as the science of the Nestorian priests may have been, it could still, with its peculiar and pharmaceutical turn, act genially upon a race (the Arabs) which had long lived in free converse with nature, and had preserved a more fresh sensibility to every sort of study of nature, than the people of Greek and Italian studies . . . . The Arabians, we repeat, are to be regarded as the proper founders of the physical sciences, in the sense we are now accustomed to attach to the word."16

The "Nestorians" were firm believers in Christian education. Every bishop endeavored to maintain a school in connection with his church, realizing the necessity of such education in a land where all government education was pagan. "The chorepiscopos of every diocese," Wrote Wigram, "appears to have had education as his special charge." Then he went on to write:

Scribes and doctors were highly honored. The school (of Nisibis) form(b a self-governing corporation, which could own property, and was extradiocesan, its head being apparently subordinate only to the patriarch. It was quartered in a monastery, the tutors being brethen of the same.... Education was free, but students were expect-d to maintain themselves.... Begging was forbidden; but students might lend money to One another at one percent, and the steward had a number of bursaries in his gift. The Course was purely theological, the sole textbooks being the Scriptures, and more particularly the Psalms.... The Church services also formed a part of the regular course; and no doubt all the approved theological works of the Church were to be found in the library. The students lied in groups of five or six in a cell, where they ate in common.... The college in Sabr-Ishu's day contained eight hundred pupils.17

During the year preceding the Mohammedan conquest Babai was the leader of the church in Persia, though there was no patriarch at the time as the king wanted a "Jacobite," a monophysite. Babai was an aggressive spiritual leader, and under him schools in sixty places were restored or built. Many books were translated or written to supply these schools, and missionaries and traveling evangelists were sent to Many places. The statement has been made that more than 2,000 books and epistles or letters, written by prominent leaders of the time, were circulating among the Christians.18

By the year 424, as the missionaries planted churches northwards, Merv, Nishapur and Herat, south of the Oxus River, all had bishops while their monks taught the converts how to read and improve their vegetable growing.19 In a day when there was little understanding of the importance of fresh fruit or vegetables to maintain health, the "Nestorian" physicians with this knowledge brought healing to many With the medicinal use of a "sherbet" of fruit juices and with the use of rhubarb, making both famous throughout the Orient. In 503 a bishop's seat was established in Samarkand. The missionaries kept Moving northward, with perhaps their greatest success being the great Kerait conversions of the eighth century, with 400,000 families converted. The Onguts and Uigurs also were largely converted. Their historian Malech has reported:

During the patriarchate of Mar Ishu Jahb II, 636, Syrian missionaries went to China, and for 150 years this mission was active.... 109 Syrian missionaries have worked in China during 150 years of the Chinese mission.... They went out from Beth Nahrin, the birthplace of Abraham, the father of all believers. The missionaries traveled on foot; they had sandals on their feet, and a staff in their hands, and carried a basket on their backs, and in the basket was the Holy Writ and the cross. They took the road around the Persian Gulf; went over deep rivers and high mountains, thousands of miles. On their way they met many heathen nations and preached to them the gospel of Christ.20

During the early years of the Mohammedan regime, the Syrian Christian churches had more freedom and peace than under the Persian kings. A concordat was signed with Mohammed whereby the Christians would pay tribute, in time of war shelter endangered Muslims and refrain from helping the enemy. In exchange they were to be given religious toleration, though they were not to proselytize, and they would not be required to fight for Mohammed.21 He had reason to befriend the Christians for a "Nestorian" had been Mohammed's teacher at one point and, in some early battles, certain Christian communities had actually fought on his side against pagan tribes.22 So much Christian influence, though highly distorted, is apparent in his teaching that Islam has been called a Christian heresy.

By the end of the eighth century the Church of the East had expanded to great distances with at least 25 metropolitans and one hundred and 50 bishops. Six bishops were the minimum to support a metropolitan. They were all under the patriarch of Bagdad, who had moved from Ctesiphon-Selucia in 763 to the newer city a few miles up the Tigris. So vast was this patriarchate that metropolitans in the outer regions were not required to attend regular synods and had to report in writing only every six years.23 Zernov describes as one of the patriarch's activities that "He sent out missionaries to Tibet and to various nomadic tribes and consecrated bishops for them who moved with their flocks over the vast open spaces of central Asia."24

The location of some of these 25 metropolitans is pointed out by Stewart, who cites the Synodicon Orientale, translated by J. B. Chabot. There the metropolitan of the Turks is placed tenth in the list and is followed by those of Razikaye, Herat, Armenia, China, Java, India and Samarkand. He also cites information, concerning the spread of the gospel in this period to the Turko-Tatar tribes, from a new manuscript translated by Mingana. This material is in the form of a letter from a Mar Philoxenus, of the eighth century, to the governor of Hirta, and makes frequent reference to Christian Turks throughout the area south of Lake Baikal. Mingana gives evidence to support his belief that the manuscript really has two parts, the latter written sometime between 730 and 790. It is this section that speaks of the many Christian Turks in central and eastern Asia. The writer states they were divided into strong clans, living nomadic lives with tents, though very wealthy, and that they ate meat, drank milk, had clean habits and orthodox beliefs. They used a Syriac version of the Bible but in their worship services translated into the Turkish language so that the people could understand the gospel.25

The manuscript also mentions that these Turko-Tartars had four great Christian kings who lived at some distance from each other. Their names are given as Gawirk, Girk, Tasahz and Langu. Mingana believes that they were the heads, or Khakans, of the four tribal confederacies of the Keraits, Uigurs, Naimans and Merkites. The populace of each king is said to have been over 400,000 families. If there were five persons to a family, this would mean two million per king for a grand total of eight million.26 If only half that many represented the actual population, it would still represent a Christian community so great it would be a tremendous witness to the zeal of those early missionaries.

Mingana declares that the credit for carrying the gospel of Christ to these tribes of central and eastern Asia belongs entirely to

the untiring zeal and the marvelous spiritual activities of the Nestorian church, the most missionary church that the world has ever seen. We cannot but marvel at the love of God, of man, and of duty which animated those unassuming disciples of Christ ... (who) literally explored all the corners of the eastern globe "to sow in them the seed of true religion as it was known to them."27

A final witness to the great extent of "Nestorian" Christianity by the beginning of the ninth century can be taken from Gibbon. Of their church he said, "their numbers, with those of the Jacobites, were computed to surpass the Greek and Latin communions."28

During those early centuries of the Christian era, as the missionaries of the Church of the East were working their way eastward, the great Chinese Empire had not been inactive in making western contacts. Hirth, in his compilation of all the references to the Western nations in the Chinese historical annals begins with a quotation from 91 B.C.

When the first embassy was sent from China to An-Shi (Parthia), the king of An-Shi ordered 20,000 cavalry to meet them on the eastern frontier.... After the Chinese embassy had returned they sent forth an embassy to follow the Chinese embassy to come and see the extent and greatness of the Chinese Empire. They offered to the Chinese court large birds' eggs, and jugglers from Li-kan.29

Another quotation, of 120 A.D., speaks of another embassy going to Ch'ang-An, the capital of China, and offering "musicians and jugglers .... They said of themselves: 'We are men from the west of the sea; the west of the sea is the same as Ta-ts'in',"30 (the sea being the Gulf of Persia). From then on the designation Li-kan is seldom used, and Ta-ts'in, with a later spelling of Ta-Ch'in, becomes the usual designation. Since the early Christians in China, as the famous Monument inscription of 781 indicates, were called Ta-Ch'in Chiao, Ta Ch'in Religion, as we shall see shortly, it is important to determine where Ta-Ch'in was. One of the early Chinese records is worth quoting at some length:

The country of Ta-ts'in is called Li-chien (Li-kin) and, as being situated on the eastern port of the sea, its territory amounts to several thousand li.. . . Their kings always desired to send embassies to China, but the An-Shi (Parthians) wished to carry on trade with them in Chinese silks, and it is for this reason that they were cut off from communication. This lasted till ... (166 A.D.) when the king of Ta-ts'in, An-tun, sent an embassy who, from the frontier of Jih-nan (Annam) offered ivory, rhinoceros horns, and tortoise. From that time dates the direct intercourse with this country.31

The country of Fu-lin, also called Ta-ts'in, lies above the western sea. In the southeast it borders on Po-ssu (Persia).... The emperor Yang-ti of the Sui dynasty (A.D. 605-617) always wished to open intercourse with Fu-lin, but did not succeed. In ... (643) the king of Fu-lin, Po-to-li, sent an embassy. [Then mention of embassies in 667, 701, and 719 are followed by this statement.] A few months after, he further sent ta-to-sheng [great-virtuous-priests, a term like Reverend, doubtless for Nestorians who arrived then] to our court with tribute.32

Saeki identifies An-tun with the Roman emperor Marcus Antonius.33 Hirth states, "We may say, in a few words, Ta-ts'in was Syria as a Roman province; Fu-lin was Syria as an Arab province during the T'ang dynasty (618-907), and as a Seldjuk province during the Sung dynasty (960-1280)."34 Saeki believes that the etymological derivation of Fu-lin is from E-fu-lin for Ephraim, between Jerusalem and Samaria.35 This opinion is corroborated by the reference in the first Chinese Christian document of 638, "The Jesus Messiah Discourse," of which we will take note later, in which we read, "Just about that time, the One (Jesus Messiah) was born in the city of Jerusalem in the country of Fu-lin (Ephraim)."36 Hirth also states it is his view "that all the first embassies sent from Fu-lin during the T'ang dynasty were carried out by Nestorian missionaries. The Nestorians enjoyed a great reputation in Western Asia on account of their medical skill."37

The Chinese records give a graphic picture of the long trade routes across their country, around the south of the Gobi desert, to the Oxus River, into Parthia and on to Mesopotamia. An alternate route was by sea from Canton, around the Malay peninsula, past the southern tip of India and into the Persian Gulf. Yule writes, "At this time, (early fifth century) the Euphrates was navigable as high as Hira, a city lying southwest of ancient Babylon ... and the ships of India and China were constantly to be seen moored before the houses of the town."38 The Chinese either turned their goods, chiefly silks, over to the Arabs here, or over to the Parthians at the Oxus River, the latter then bringing them to Hira. There they were transshipped around the Arabian peninsula, up the Red Sea to Solomon's Ezion-geber or the Aelana (modern Akabah) of the Romans; from there caravans carried them to Petra, the great market city, to sell them to the western traders. Of Petra Hirth writes:

During the first two centuries A D., Petra or Rekem, was the great emporium of Indian (and, we may add, Chinese) commodities, where merchants from all parts of the world met for the purpose of traffic.... Under the auspices of Rome, Petra rose, along with her dependencies, to an incredible opulence.... This prosperity was entirely dependent upon the caravan trade, which at this entrepot changed carriage, and passed from the hands of the southern to those of the northern merchants.39

It was not until the seventh century that two events brought about the demise of this great trading center. The first was the smuggling of silkmoth eggs into Syria, concealed in a bamboo cane, the presumption being that it was done by "Nestorians,"40 with the result that "by the end of the sixth century (Syria) appears to have been meeting the west's demand for the raw material."41 The other was the fall of Petra to the Mohammedans after 640. It was without doubt through these early oriental traders that the Syrian Christians of "Ta-Ch'in" first heard of the greatness of the Chinese Empire and determined to take the gospel there. It is even very likely that they arranged to go with returning merchants. We know that the time was early in the T'ang dynasty, when the empire had its widest extent, its soldiers governing 811 the way to the Oxus River, for the Nestorian Monument declares the year of their arrival at the capital of Ch'ang-An (or Hsi-an-fu) to be 635 A.D.

Evidence of Christian Activity in China, 635-845

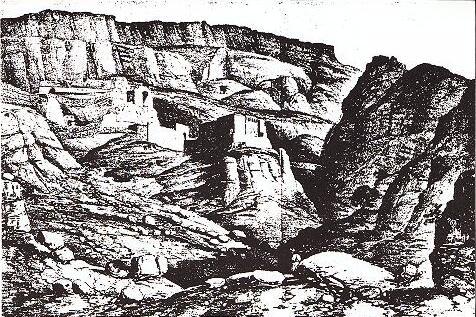

Of all the evidence of the activity of the Christian missionaries in China which have come to light in the era of modem history, none has been more dramatic than the report of the discovery of the "Nestorian" stone Monument by a Jesuit priest in 1625. It had actually been dug up by Chinese workmen, under an old wall, two years earlier "at a certain place in Kuan-chung"42 which Saeki identifies as the site of a "Nestorian" monastery and church near Chouchih, about 30 miles from Hsi-an-fu, the modern name for the old capital, Ch'ang-An. When Trigault, the first Roman Catholic missionary to see it, took rubbings it had been moved to Hsi-an-fu, probably late in 1624. It is still there today, while an exact replica exists in the Vatican museum, with still another in Japan at the Shingon (True Word) Buddhist Temple on Koyasan.

When announcements of it were first made in Europe some doubted Its authenticity, claiming it was a "pious fraud" of the Jesuits to show the antiquity of their Church's missionary efforts.43 Of this Gibbon has written:

The Christianity of China, between the seventh and the thirteenth century, is invincibly proved by the consent of Chinese, Arabian, Syriac, and Latin evidence. The inscription of Hsianfu, which describes the fortunes of the Nestorian church, from the first mission, A.D. 636, to the current year 781, is accused of forgery by La Croze, Voltaire, and others, who become the dupes of their own cunning, while they are afraid of a Jesuitical fraud.44

One of the criticisms of it was that the style of writing "is too modern to be credited with a thousand year's age."45 Of this Hirth says it "is utterly baseless .... A Chinese connoisseur, who had never heard of the Nestorian Tablet, and to whom I showed a tracing of it, declared it at once as 'T'ang-pi,' i.e., written in the style of, and containing the slight varieties adopted during, the T'ang dynasty."46

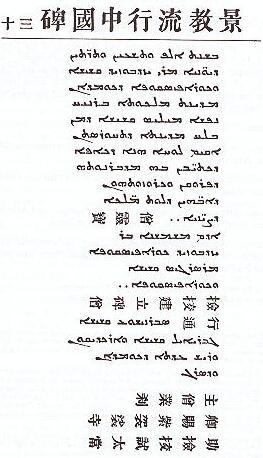

The stone itself stands over nine feet high, three feet wide, and one foot thick, with two dragons carved over the top edge, a small "Nestorian" cross near the top center, and nine large Chinese characters below it reading, "A Monument Commemorating the Propagation of the Ta-Ch'in Luminous Religion in the Middle Kingdom (China)." It is stated to have been composed by a Persian presbyter named Adam and erected on "the 7th of the First Month of 781 A.D." by one "Lord Yazedbouzid" chorepiscopos of Hsi-an. Adam's Chinese name is given as Ching-ching, and in Syriac, Saeki says, it is stated on the stone, "Chorepiscopus, and Papash of Chinestan."47 The names of some 70 missionaries are given in Chinese and Syriac at the end of the 2000-word inscription.

The inscription describes how the missionaries arrived in 635, were welcomed by the emperor, and instructed to put some of their writings into Chinese. (A later document, "The Book of Praise," indicates that there were then 530 Christian manuscripts at hand.)48 They were given permission by proclamation in 638 to stay and teach, and a monastery was built for them outside the city in the I-ning ward. The names of the T'ang emperors are mentioned and praised as benefactors, some sending their portraits to be hung in the monastery and providing generous patronage. In return, the priests prayed for them and their ancestors daily. The arrival of 17 reinforcements from TaCh'in in 744 is mentioned which is in harmony with a Syrian church record of the departure then of these 17 missionaries49 Comment on the doctrinal portion of the inscription will be made later.

A Japanese scholar, Dr. Takakusa, while studying "The Catalogue (of the books of) teaching of Chakya (Buddha) in the period of Chanyuan" (785-804 A.D.), discovered a passage referring to the Christian presence in Hsian, and particularly to that of Adam Ching-ching. The passage referred to Prajna, the Indian Buddhist scholar who came to China in 782. It stated: "He translated together with Ching-ching, Adam, a Persian priest of the monastery of Ta-Ch'in, the Satparamita sutra from a Hu (Uigur) text, and finished translating seven volumes."50 The Catalogue writer went on to complain that Prajna knew neither Uigur nor Chinese and that Ching-ching knew no Sanskrit nor understood Buddhism, but both were seeking vainglory.

He further mentioned that "They presented a memorial (to the Emperor) expecting to get it propagated" but that the Emperor (Tetsung, 780-804) was wise and after examining their work determined that it was poorly done, "the principles being obscure and the wording vague. The emperor then declared that the Ta-Ch'in religion and Buddhism were entirely opposed to each other; Ching-ching handed down the teaching of Mi-shih-ho (Messiah, using the same three Chinese characters as were used on the Nestorian Stone) while (Prajna) propagated the sutras of the Buddha. It is wished that the boundaries of the doctrine may be kept distinct."51 With that the emperor forbade the two from working together further.

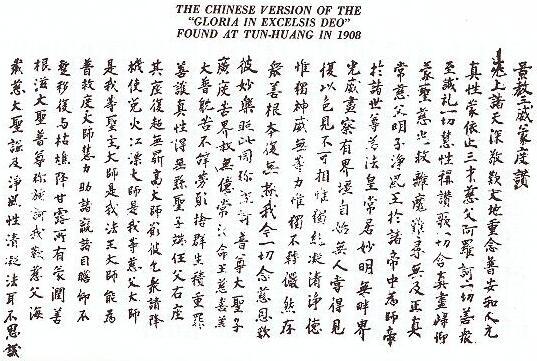

The nine Chinese manuscripts and two Syriac ones found in China--some of them found in a cave sealed in 1036 in Tun-huang52 With one claiming that it was 641 years since Jesus Messiah was born and another giving the Chinese dating corresponding to 717--are also strong evidence of the presence of the Christians in China. These manuscripts will be described and examined for their theological content later.

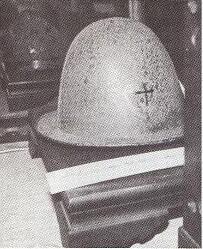

Striking evidence of these early Christian times is presented by the remains of the monastery built at Chou-chih where the Monument vas found. The building has long since crumbled away, but eleventh century Chinese poets have mentioned it in their poems by the name of Ta-Ch'in Ssu (temple), and in 1933 a famous tower on the property was still standing while the people of the area still called the place Ta-Ch'in Ssu.53 Further, tombstones with "Nestorian" crosses on them, in areas where the local records indicate they date from the Tang era of the eighth and ninth centuries, have been found in different places in China.54

Farther west, in the area of the salt sea in Turkestan called Lake Issyk-kul, over 600 tombstones with crosses on them were found in two ancient cemeteries. The oldest date was 858 and the latest 1342. The inscriptions on many were in the Syriac script but the names indicate that these people were native converts. One inscription reads, "This is the grave of Pasak--The aim of life is Jesus, our Redeemer." Another states, "This is the tomb of Shelicha, the famous Exegete and Preacher who enlightened all the cloisters with Light, being the son of Exegete Peter. He was famous for his wisdom, and when preaching his voice sounded like a trumpet."55 Among the names are those of "nine archdeacons, eight doctors of ecclesiastical jurisprudence and of biblical interpretation, 22 visitors, three commentators, 46 scholastics, two preachers and an imposing number of priests."56 A chorepiscopus is also buried there with mention that he came from a nearby city. This last resting place of the saints of 700 years ago is mute witness of a past genuine Christian presence. As Stewart says of it, "Only in the grave stones from Semiryechensk (its Russian name) do we find evidence of the rich and varied Christian life which prevailed in one tiny corner of these extensive areas, filled as they once were with Christian communities."57

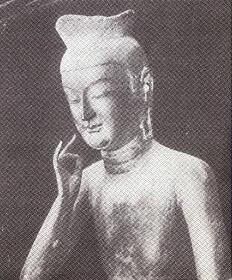

The Tun-huang cave of western China, sealed, as mentioned earlier, in 1036 and not opened until about 1900, contained over 2,000 manuscripts, including some Christian ones. Also it had a painting on its walls of a Christian bishop on horseback, carrying a bishop's rod with a "Nestorian" cross on the end. In addition there was in the cave a silk screen painting of a robed man wearing a crown with a gold cross, with two other crosses around his neck, holding a bishop's rod. This painting was acquired by the Sir Aurel Stein expedition in 1908, and is now in the British Museum in London.58 It seems to be beyond doubt a painting of an Oriental Christian bishop of the pre-1000 A.D. era. (See back cover painting.)

One of the intriguing aspects of the painting is that the right hand is held up with the thumb touching the tip of the second finger. The "Nestorians" were well known for their fondness for symbols. Was this posture a double witness to the Trinity with its triangle of thumb and finger and the remaining three fingers pointing upwards? Buddha images and paintings of earlier centuries usually show him with hands clasped in his lap or an upraised hand with open palm. In later centuries, however, it is not uncommon to see Buddha figures with the right hand raised in the posture of this painting of a Christian bishop. The question as to who used this symbol first is not answered, but it does seem to have more significance as a Christian Witness.

A tomb excavated in Manchuria in 1927 contained crosses and coins of the early eleventh century. Historical records show that those buried there were Uigurs, a Tatar tribe converted by the early missionaries.59 Saeki feels that the Syriac script still found in some places in Manchuria today, which this writer has seen himself over some building entrances, is "nothing but the greatest Nestorian relics of all."60

In addition, numerous references to the Persian missionaries in the land appear in the Imperial historical annals of China. For instance, the full proclamation of permission, issued in 638 and referred to on the Monument, appears with "the Persian monk A-to-pen (Abraham) bringing scriptures and teaching from far" specifically mentioned.61 Again, "In the ninth month of the twentieth year K'ai-yuan (October 732) the king of Persia sent the chief Pan-na-mi (Barnubi) with the monk of great virtue, Chi-lieh (Cyriacus) as ambassadors with tribute."62 But these casual references are too numerous to mention further. The evidence of the presence of the "Nestorian" missionaries in China during the T'ang era is incontestable. On the basis of the Chinese records alone Hirth states dogmatically, "all the first embassies sent from Fu-tin during the T'ang dynasty were carried out by Nestorian missionaries."63

In Japan and Korea also, evidence of a past early Christian presence survives. Two beams of an ancient temple, dating from the late seventh century, with crosses on them and having inscriptions identified by professor Sayce as being "in an alphabet akin to Syriac,"64 are in the Tokyo National Museum. In northwest Japan is a large tomb, dating from about the same time, known to the local people as "the tomb of Jesus." In all probability it is the tomb of a "Nestorian" Christian who preached Jesus, perhaps even bore His name, who was buried there in the tomb period. The Shoku-Nihongi, published in 797, refers to the return from China in 736 of an envoy who brought with him "a Persian by the name of Limitsi and another dignitary of the church of the Luminous Religion (Kei Kyo-Chinese, Ching Chiao) called Kohfu."65 Elsewhere in Japanese history the Persian is referred to as Rimitsu, the physician. The Empress Komyo was very much influenced by his teaching and later built a hospital, an orphanage and a leprosarium, works of mercy typical of the "Nestorian" practical Christianity, but not of the Buddhism of that day.

One of the most sacred objects of the Shingon sect of Buddhism at the Nishi-Honganji Temple in Kyoto, founded by Kobo Daishi after he returned in 806 from China's capital and contact with the "Nestorian" monastery there, is a copy of the early missionary manuscript, "The Lord of the Universe's Discourse on Almsgiving," a commentary on the Sermon on the Mount and other Matthew passages. It is said that Shiriran spent hours daily studying this Christian document.

The oldest structure in ancient Kyoto is the Lecture Hall of the Koryuji Buddhist Temple, rebuilt in 1165. According to Teshima, the original building was not Buddhist but Christian, erected in 603. This building burned down and was rebuilt about 818 as the Koryuji Buddhist Temple. When this writer visited it in 1976, he was given a pamphlet describing something of the temple's history but nothing of its possible Christian origin.

Amazingly, however, the pamphlet had on the cover page as the first two of five Chinese ideographs the characters Tai Shin, the same being the first two on the famous Nestorian Stone (in Chinese Ta Ch'in) indicating the Mediterranean-Mesopotamian area homeland of the missionaries. Immediately following the Tai Shin, in parentheses, was uzu masa in Japanese hira gana script. Saeki claims that the ethnic origin of these two, non-Japanese words (the meaning of which Japanese scholars can only speculate) is the Aramaic Yeshu Meshiach, Jesus Messiah. Remarkably the temple thus bears the names of its original identity, Tai Shin, the place of origin of the religion and the missionaries who brought it, and of Jesus Christ, the One once worshipped at that ancient church. Further identity of uzu masa is in a song of 641 recorded in the ancient history text Nihonshoki: "O Lord, our Uzu Masa, How majestic is your name in all the earth! You are truly God of gods."66 The identification of Uzu Masa with the God of gods and Lord of the earth could not be clearer.

The most revered object in the Koryuji Temple is the pine carving of a sitting Miroko (Maitreya) Buddha, brought over from North Korea in the ninth century. The features, including a large, thin nose, are Semitic, not Far Eastern. This is the Buddha of the next coming, whose return to earth will bring marvelous deliverance to all living beings, a concept that arose in Buddhism about the beginning of the fourth century A.D. in India, at a time when Christianity had made great progress there. Maitreya is held to be the Hindi version of the Greek word Metatron, change of time, denoting the time of the coming Messianic deliverance and new age. Interesting also is the fact that the figures of the right hand of this Buddha of the future coming are in the same posture of three upright fingers, with thumb and one finger forming a triangle, similar to the posture of the bishop's hand in the painting of the "Nestorian" bishop of China.

In southwest Korea there is a cave with an entrance said to be in the pattern of the Christian cave-churches of Syria. Some 16 stone plaques are built into the walls with figures and implements carved on them which do not represent Koreans or their culture but rather seem similar to Syrian Christian scenes. The cave was built in the seventh century in honor of a "black monk" who is believed to have come to Korea the previous century.67 Dr. J. G. Holdcroft, for many years a missionary in Korea, who describes this cave, also speaks of interviewing Dr. J. S. Gale, an American scholar of Korean antiquities, concerning the possibility of an early Christian presence in the Orient. Dr. Gale replied: "Oh, yes, all of Asia had the Gospel but lost it." Dr. Holdcroft continued, "He stated also that in the ancient Korean literature, which is all written in the Chinese character, there are even references to God (Father, Son and Holy Spirit). `But,' said he, `I have never found any Korean scholar who knew where those quotations came from'."68 The Korean alphabet, a very simple one to learn, is held to have been a gift of Christian missionaries over a millennium ago, to have been revived by a Korean king some 500 years ago and then discarded, only to have been revived again by Protestant missionaries for the gospel's propagation during the past century.69 In the providence of God, the gospel was indeed preached throughout Asia but through compromise, ignorance of Scripture, and distortion, it became so perverted as to become almost indistinguishable from paganism and was lost to the peoples to whom it came.

Decline o f the Christians in China from 845

In the year 845, a great disaster befell the Christian cause. An act of proscription was promulgated by the emperor. The Christians were not the prime targets but were definitely included. The act was directed against the many Buddhist monasteries and temples by the emperor, "hating the monks and nuns because (like moths) they ate up the Empire. He decided to have done with them," as one report puts it.70 The act is referred to in the Chinese historical records with specific reference to the Ta-Ch'in religion, Christianity.

When Wu Tsung was on the throne he destroyed Buddhism. Throughout the Empire he demolished 4,600 monasteries, 40,000 Refugees, settled as secular subjects 265,000 monks and nuns, and 150,000 male and female serfs, while of land (he resumed) some tens of millions of ch'ing. Of the Ta-Ch'in (Syrian Christian) and Mu-hu Hsien (Zoroastrian) monasteries there were over two thousand people.71

A further report states:

The rest of the monks and nuns, along with the monks of Ta-Ch'in ... all were compelled to return to the world. A period was fixed for the demolition of those monasteries which were not to be allowed to remain. (A few were to be designated objects of art.) Materials from the demolished monasteries were to be used for repairing yamens and post-,stages. Bronze images, mirrors, and clappers were to be melted down for coinage.72

Although this act was withdrawn two years later, the damage was done. Buddhism never recovered from the blow, which may account for the fact that it never became the dominant force in China that it became in Japan.73 Further, the Christian work definitely went into eclipse. The troublous times which followed the disintegration of the Tang dynasty, with the sacking of cities and slaughter of the inhabitants, as occurred in Canton where many foreigners died,74 must have been also a contributing factor to the eclipse of Christian churches begun over 200 years earlier.

Foster gives the report of an Arabic record, written in Baghdad about 987, which tells of the writer meeting with a Christian monk who had seven years earlier been sent to China by the patriarch, with five others, "to bring the affairs of Christianity in that country to order." This young man told the Arab writing the account, "that Christianity had become quite extinct in China. The Christians had perished in various ways. Their Church had been destroyed."75 The Christian monk had then returned to Baghdad. Whether this delegation had really made an adequate tour is problematical. Saeki has given evidence to show that the monasteries and churches in Chouchin and Hsi-an continued in existence long after this time. Also in 1093 the patriarch Sabrisha III appointed a bishop George to Cathy.76 Nevertheless the evidence is that the progress of the Christian churches in China went through a noticeable decline during the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

Saeki reports that the famous Taoist scholar, Chia Shang-hsiang, who compiled the life of Lao-tze about 1100 A.D., apparently was unaware that the Christians had ever been present, for he classified "the remnants of the Chinese Nestorians among the 98 kinds of heretical cults or religions then known to the Taoists. He named it `The Messiah Heretics' and put it in the 49th of the 98 heretical cults or religions prevailing in the 81 countries around Liu-sha and its neighborhood."77

A remarkable example of the influence of Christianity on pagan religion can be seen in various concepts and rituals of the "Nestorians" being adopted, in a distorted form, by Buddhists, thereby radically affecting their tradition,78 as witnessed by the development of the Lama sect in Tibet. Buddhism reached Tibet in 640, sometime before Christian missionaries did, but by the end of the first millennium, as striking resemblances show, Tibetan Buddhism had incorporated the Far Eastern "Nestorian" clergy's increasing preoccupation with demons, holy water, prayers for the dead, confession and red vestments as well as their traditional monastic system and hierarchy topped with a patriarch-in Lamaism's the Delai (All Embracing) Lama.

Although indications seem to warrant the conclusion that the curtain had fallen, finally, at the end of the tenth century, on the drama of Christianity in China, a story which opened so auspiciously at the beginning of the seventh, it was not to be so. The evidence of its great revival three centuries later will be given in the next chapter.

We have already observed that during the seventh and eighth centuries the missionaries began to take the gospel into the northern tribes of that vast area of plains later known as Mongolia. An interesting witness to the extent of the conversion of many of the southern tribes is given in the report of Benedict the Pole who accompanied Friar John of Plano Carpini on his mission from the Pope to the Khan's court in 1245. As they journeyed north of the Black Sea and crossed the Don River, Benedict wrote, "next the Alans who are Christians and then the Khazars who are likewise Christianà.After, the Circassians, and they are Christians. And finally, the Georgians, also Christians."79

The first of the northern tribes to be almost completely converted were the Keraits south of Lake Baikal. It was a later chief, the uncle of Genghis Khan, who became famous to the western world as the almost legendary Prester John.80 From the Keraits the gospel reached the neighboring Naimans to the west and the Uigurs (ogres to Europe) to their west. The Manichean sect also succeeded in penetrating the latter tribe and converting a portion of it. By then, during the eighth century, the Uigurs had replaced the East Turks as the strongest power of the area. The Onguts north of the big bend of the Yellow River became Christians, but the Mongols and Tatars east of the Keraits were more resistant.

The Uigurs were open to civilizing influences and became a literate people through a script worked out for them by the Christian missionaries, the alphabet being the Syriac with additional letters for the new sounds. The later Mongols, under the Khans, adopted this Uigur script for writing their own language. The Christians, at their linguistic headquarters in Merv, sought to have the languages of all the tribes put into writing that they might have constant access to the gospel. The effectiveness of their mission is testified to by an inscription, found at Kara-Balsaghun in this Uigur writing, attesting an astonishing transformation brought about through the conversion of the Uigurs. It states, "This land of barbarous customs, smoking with blood, was transformed into a vegetarian state, and this land of slaughter became a land devoted to good works."81 Throughout the reign of the Khans, the Uigurs were used as their secretaries.

Saeki has given a translation of an interesting inscription that shows the influence of the Uigurs and their religion in China just before the Khan conquest. The inscription is on a stone monument erected on the side of the avenue leading to the tomb of the honorable Ma, the governor of Heng-Chow. It states that when the Chin emperor had conquered Liaotung (north of Peking) he had the Uigurs of western Kansu moved there. During the reign of the Emperor T'ai-tsung (1113-1134), he heard of the image (lit., portrait) worshipped by the Uigurs, and requested to see it. The inscription states that it was taken out of "the House where the Uigurs meet and sing their hymns"82 to be shown the emperor. He was so impressed that he emancipated all their slaves and gave them presents of money and land. Less than a century later one of their leaders, Ma Hsi-chi-ssu, (a corruption of the Syriac Mar Sargis) became the famous General Ma Ch'ing-hsiang and governor of Heng-Chou. In the genealogical table of the Ma family, an excerpt of which Saeki translates, appears the following statement: "The ancestors of the Ma family were the descendents of the Niessuto'o-li (i.e. Nestorian) noble family of the Western lands."83 This seems to be one of the few times the "Nestorians" are referred to in the Chinese records by a transliteration of that name rather than by the name Ta Ch'in, a reference to their land of origin..

For four centuries Christianity spread through these primitive tribes, although in many instances it was weak through ignorance and compromised by the superstitious fear of and belief in the shaman, the soothsayers. It was not until the coming of Genghis Khan, with his conquest of all the tribes and amalgamation of them into the Mongol Empire, including his conquest of China, that the Church of the East came to its greatest influence and extent in the Far East.

Genghis, whose original name was Temuchin, was born in 1167, a son of the chieftain of the Mongol tribe, one of the smaller clans east of the ruling Keraits. His father named him Temuchin (Finest Steel) after a defeated warrior he admired. In subsequent battles with their hereditary enemies to the east, the Tatars, the father was killed. Temuchin then made a treaty with the Kerait leader, a Christian with the title Prester (Presbyter) John. Gradually together they conquered the neighboring tribes and through generous terms won them over. But leaders of the aging Prester John foolishly moved him to attack the Mongols, resulting in the defeat of the Keraits and his death. By 1205 Genghis was the sole suzerain of all the tribes, the ruler of the Mongolian plains. The next year he called for the leaders of the tribes to assemble for a general kuriltai (diet) and at this council they elected him their emperor with the new name Genghis Khan, Emperor of All Men.

In 1211 the new emperor began his great war with China. It was then a divided kingdom, with the Manchu Chin dynasty ruling north of the Yellow River, and the Sung dynasty south of the river. Genghis conquered all the way across north China, destroying cities that withstood his thousands of horsemen (each of whom led four horses in addition to the one he rode) until he laid siege to Yen Ching, the capital, near the present Peking. The city fell and the undefeatable Khan turned his armies home to his capital, Karakorum, and then on to a great southern campaign. Before reaching home he carried out what became a common practice before each winter; he had his soldiers slaughter the vast mass of conquered people he had used as slave workers during the campaign. Concerning this practice, Lamb has made the following comment:

It appears to have been the custom of the Mongols to put to death all captives, except the artisans and savants, when they turned their faces homeward after a campaign. Few, if any, slaves appear in the native lands of the Mongols at this time. A throng of ill-nourished captives on foot could not have crossed the lengths of the barrens that surrounded the home of the nomads. Instead of turning them loose, the Mongols made an end of them - as we might cast off old garments. Human life had no value in the eyes of the Mongols, who desired only to depopulate fertile lands to provide grazing for their herds. It was their boast at the end of the war against Cathay that a horse could be ridden without stumbling across the sites of many cities of Cathay (China).84

On the southward march, Genghis Khan's armies defeated the last of the nomad tribesmen of "the Roof of the World" and then crossed the T'ien Shan range to face the great Muslim power of the Shah of Kharesm. At this time Islam was at the height of its martial power. The crusaders had been driven back to their coastal forts and the western Turks were pushing the enfeebled Greek empire out of Asia. The great army of the Shah was equipped with superior armor - steel swords that could be bent double, chain mail, light steel helmets, gleaming shields and even some guns. They also used Greek fire and understood flaming naphtha and the use of catapult machines. This was the greatest military power Genghis had yet faced. But he totally overthrew it.

As Genghis remained behind to reduce the great cities of the Kharesm empire, he sent two of his generals, with 20,000 cavalry, to pursue the fleeing emperor. They followed him to Baghdad, then north into Georgia, and, following news of his death, they crossed the Caucasus Mountains, defeated a Russian army of over 80,000 and returned to their Khan by way of circling the Caspian Sea. It has been called an amazing march, "the greatest feat of cavalry in human annals."85 Meanwhile Genghis reduced city after city--Kashgar, Balasaghun, Samarkand, Bokhara, Herat, Merv, Balkh, Nishapur--some of the greatest cities in the world, with all their wealth, culture, industries, libraries, and ancient art were destroyed.

Some descriptions of the extent of these destructions--with many of the cities being centers of strong Christian communities - have been given. When Herat fell, 1,600,000 people were taken out of the city and killed, this once magnificent capital eventually reduced to 40 persons. Kharesm's population was divided up with each Mongol soldier being given 24 people to kill, until the population of 1,200,000 were exterminated.86 Merv, the great educational and translation center of the Christians, had its population of 1,300,000 divided into three masses of men, women and children (excepting only 400 craftsmen whom the Mongols wanted), who were then forced to lie down while they were strangled or slashed to death.87 Nishapur, another Christian center, had its population of 1,747,000 also put to death. Muslim and Christian alike suffered terribly in this first invasion of the Mongolian hordes. When it was over, Genghis Khan ruled from Peking to Mesopotamia, from the Knieper River to the Indus, an area covering eight longitude. In all of this "he succeeded in destroying a larger portion of the human race than any modern expert in total warfare."88

In 1222 Genghis returned to Karakorum for a few years rest, but in 1225 he was on the march again, southeastward, to conquer the Sung dynasty of south China through Kansu, the center of the Tibet kingdom. Here he died in 1227. The escort that accompanied the funeral death cart to Karakorum had orders to strike down every individual met so no word of the Khan's death could leak out in China. Genghis had called himself "The Scourge of God," believing, as his great seal declared him to be, "The power of God on Earth; the Emperor of Mankind." In spite of his frightful behavior towards his fellow men, he constantly affirmed that he believed in one God whose will he was carrying out. His yasa or code of laws regulating Mongol life began with the statement: "It is ordered to believe that there is only one God, creator of heaven and earth, who alone gives life and death, riches and poverty as pleasures Him-and who has over everything an absolute power." The influence of the Christianity of the Keraits, Genghis' strongest tribe, is without a doubt apparent in this statement with its witness to the sovereign God of creation and providence. The next rule of the yasa shows his sense of religious toleration, a mark of all the Khans. "Leaders of a religion, preachers, monks, persons who are dedicated to religious practice, the criers of mosques, physicians and undertakers are to be freed from public taxes and charges."89

Genghis Khan's rule introduced the pax Tatarus. It was completely safe to travel from the Pacific to the Black Sea with a Mongol safe conduct. He set up a pony express, with way stations every 25 miles for a change of horse, and lodging every 100 miles. The envoys from the pope in 1245, led by John Plano Carpini, and from King Louis of France in 1253, led by William of Rubruck, tell of traveling by this highly efficient route, month after month, the more than 6,000 miles from their homelands to Karakorum. Genghis gathered excellent Chinese and Christian administrators and scribes about him who organized his conquered domains efficiently. He required the Uigurs to give the Mongols a written language, and Carpini has written, "These people, (the Uigurs) who are Christians of the Nestorian sect, he also defeated in battle, and the Mongols took their alphabet, for formerly they had no written characters; now however they call it the Mongol alphabet."90 This Mongol script from the Uigur alphabet (gift of the early Christians) became the usual medium of writing throughout the vast area of the Mongol empire and, as Stewart says, "the parent of alphabets made use of by other more backward tribes such as ... the Manchus." As an illustration he speaks of an ancient Uigur manuscript existing which "supplies us with a specimen of the Nestorian alphabet as adapted to the use of the Ugro-Altaic tribes. It shows the connecting link between the Nestorian writing and the various Mongolian alphabets."91

The Mongol emperors kept physicians in their courts who were available to the people. Among them the Christian physicians, with their knowledge of the use of rhubarb and sherbet, were the most respected. Rubruck mentions seeing rhubarb used at Karakorum while Saeki translates a Chinese description of a Christian physician using sherbet at the court of Kublai Khan. The writing speaks of physicians who were of the Yeh-li-k'o-wen religion (the religion of Christian priests) who made sherbet from fragrant fruits by boiling them and mixing with honey. She-li-pa-ch'ih (a man of sherbet) is the name of his office. His Excellency had the hereditary skill (to make sherbet) and it often had miraculous effect. The Emperor specially granted to him a gold tablet and made him devote himself solely to the office."92 The missionaries' knowledge of the value of fruit and vegetables for the sick and their physicians' effective use of that knowledge was well known in the Khan empire.