AP)

AP)

There were those who joined IS because they believed in the caliphate, and some who did it for status or material gain. And then there were those who had the courage to revolt despite the very real risk to their lives.

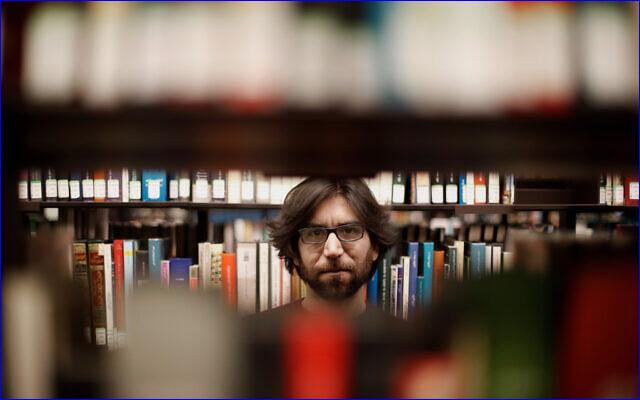

This is the story of one of those heroes. Omar Mohammed, a then a history professor at the University of Mosul, never took up arms, fired a shot, or confronted IS.

"The pen is mightier than the sword," Mohammed told Zman Yisrael, the Hebrew sister site of The Times of Israel.

His weapons of choice were his blog, Twitter, and Facebook. His nom de guerre was Ein al Mosul, or Mosul Eye, and his avatar was a lamassu -- a winged Assyrian deity of protection.

Via his Mosul Eye accounts, Mohammed reported in real time what was happening under IS rule in his home city. He told of the atrocities and gave name to the victims, sending a message to the members of the so-called caliphate and fellow residents of his city.

"I wanted to prevent IS from writing history so that nobody would say in a few years that this time had been so great," Mohammed says.

Related: Timeline of ISIS in Iraq

Related: Attacks on Assyrians in Syria By ISIS and Other Muslim Groups

Life had always been difficult and fraught with danger in the northern Iraqi city on the banks of the Tigris River. The city in Nineveh Province, where the prophet Jonah who foretold the city's destruction and survived in the belly of a whale for three days is buried, has become a large metropolis of over 1.5 million people. It has a Sunni majority, but also housed ancient communities of Jews, Christians, Assyrians, Kurds, Circassians, and Yazidis.

"People were stopped at security checkpoints by [Iraqi] soldiers every day, just because they were Sunni and the soldiers were Shiite," Mohammed says, "and there were occasional IS attacks. In my neighborhood there was a post that was blown up every Friday, and then the next day the security forces would come back and set up a new checkpoint. It went on like that every week for a year."

The Iraqi army fled the city in a panic in June 2014 when IS members stormed the area. They arrived in Toyotas, brandishing weapons and waving black flags. A few days earlier, IS members had slaughtered over 1,000 security forces recruits in an act that shocked the country and gave them the psychological edge.

The new rulers immediately made it clear that they intended to remain in the city for the long run.

"They executed people within a very short time," says Mohammed. "They had a list prepared in advance, and in my neighborhood seven people were executed in hours. Then they made their laws. In August, they committed the crimes against the Yazidis, expelled the Christians, and declared the area an Islamic state."

"Everyone who lived in the city lived under the laws of Islam," Mohammed says. "They began to behead people in public, cut off hands; they threw members of the LGBT community off of tall buildings, stoned men and women for adultery, lashed people for minor crimes, and even crucified people. They created a kind of horror-inspired game in which the victims fought each other. They put explosives on prisoners and if they moved too fast, the bomb exploded."

An attempt to erase history

For Mohammed, who was a historian, there was an added horror when IS began methodically destroying Mosul's cultural and historical heritage.

"The first thing they did was eliminate the history of Mosul," says Mohammed. "They destroyed statues of local cultural heroes, the library, the historical museum, the tomb of the prophet Jonah, and other sites. Then I realized it was a campaign against Mosul and against history -- everything that symbolized the ethnic diversity of the city. For me as a historian it has been unbearably difficult. I have no words for how awful it was. That's why I started writing the blog."

Mosul Eye began with reports in English -- first as a blog and then on Twitter and Facebook -- and became a credible source for what was happening in the city. The Eye saw, and reported daily life under the horror of IS to the outside world.

Mosul Eye named the victims of IS executions and described the sexual trafficking of Yazidi women and girls who were sold for just hundreds of dollars and sometimes returned to the market after being assaulted. It also reported on IS military activity in the city and on the bridges over the Tigris. Mosul Eye became an important media outlet for the city's residents and the international press -- as well as the intelligence agencies.

"ISIS executed a person by crucifixion," reported Mosul Eye on May 12, 2015. "This is the first time they have crucified someone. The charges were espionage and theft."

Thanks to his deep knowledge of Islamic history, Mohammed gained the respect of IS members and was able to interact with them without arousing suspicion. He kept two laptops in his house -- one clean, with Islamic texts and wholesome photos, and the other which he used to communicate with the world. His internet connection was paid for under a false name.

He dressed like a devout follower and grew his hair and beard long, trying not to attract attention, but felt increasingly walled in. After posting what his neighbor, an IS member, confided to him about an air raid that had killed several of the group's leaders, Mohammed had a moment of panic when he realized what he'd done.

"I thought to myself, 'Oh God, what am I doing, I'm the only one he told,' and deleted the post that night," Mohammed says. "Later, I invited him to dinner by the river to see if he was suspicious -- and of course he wasn't, or I wouldn't be talking to you now."

Members of IS indeed were watching Mosul Eye. Commenting on his Facebook page, they didn't threaten his life, but said he'd wish for his own death after they caught him.

Rumors about Mosul Eye's true identity swirled around the city. Some thought the blogger was an elderly historian; others claimed it was a Jewish man who'd left the city but was still emotionally attached to it. Others thought it was a woman, or possibly even psychological warfare employed by the CIA. All of these theories helped protect Mohammed's identity, but time was running out.

"As the attack on Mosul intensified and air strikes began, IS shrank, retreated and became more and more concentrated within the city. In my neighborhood there were more and more of them," Mohammed says. "My close neighbors were IS; I had observation posts next to me and I felt they were way too close -- that the area where I could move and report was getting smaller, and the chances of being caught higher."

Citing the safety of his family -- Mohammed says he was willing to pay the "ultimate price" to continue his work exposing IS -- the blogger left Mosul in late 2015. The exit was surprisingly very easy.

Smuggled past checkpoints to the Syrian city of Raqqa, and from there, along with other refugees, smuggled by a second operative into Turkey, Mohammed continued to report remotely about the war and destruction in Mosul until its liberation from IS in July 2017. He didn't feel safe exposing his identity until that December.

"Oh boy, I always thought it was you," he remembers his mother saying.

Today Mohammed lives in Paris and operates an updated version of Mosul Eye. His posts follow the city's slow restoration, the corruption running deep among Iraqi officials, as well as cultural and historical events -- including those relating to Mosul's Jewish history. But restoring the city requires more than just rebuilding its physical infrastructure.

A city in need of psychological restoration

Mohammed says that IS destroyed Mosul's social infrastructure by creating conflict and sowing animosity between the city's diverse communities, often in the name of Sunni Islam.

People are still in shock, he says, adding that the citizens of Mosul need psychological treatment and therapy.

"Imagine the impact on children who have seen beheadings, what impact on their lives, not to mention those whose parents and relatives were executed, or those whose limbs were cut off, and those whose family members were thrown off high buildings," Mohammed says.

"Today you see people smiling, but we do not know what is going on inside. When I talk to the residents, they are still scared, shocked, sometimes confused, they still think IS is there," he says.

"I had a brilliant student who wanted to be a professor of history; he joined them. I cried when I saw what happened, but I was also afraid of him. It's a terrible feeling to care about someone, and to fear them too. I could not do anything to save him. They played with his brain. I mourn him to this day," he says.

Continuing to cope

Mohammed says he still suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder.

"[After escaping,] it took me half a year to realize I was still alive. I still remember the eyes, the blood flow, when people were beheaded, the heat as if the blood touched me. I looked at their faces, I felt I could recognize them even under the executioner's mask," he says.

But, Mohammed says, his drive as a historian helps him cope with the effects of PTSD. He cites Victor Klemperer, the German Jewish historian who documented World War II from inside Germany, as an inspiration.

"I had a golden rule -- don't trust anyone and report everything," says Mohammed. "But when you don't trust anyone for two or three years, it's hard to trust people again."

The blogger says that without music, he would not have been able to survive life under IS control.

"In Mosul, I listened to violinist Itzhak Perlman, and he is the man," Mohammed says. "That's the music I would always listen to -- like 'Jewish Town' from the 'Schindler's List' soundtrack. When I listened to his music, I felt like someone was injecting life into my heart."

Along with the pain and trauma, Mohammed is paying another price for his heroic actions. He is still unable to visit Mosul, and hasn't seen his mother or the rest of his family in five years. His brother was killed in battle in their hometown, and Mohammed is unable to visit his grave.

"I quietly carry an ongoing silent grief within me, because if I articulate it, it would be difficult for readers, myself, and my mother. I want to maintain the positivity of Mosul Eye because I have a mission to rebuild the city," he says.

"Once I feel the mission is complete, I will sit with myself and cry as I have wanted to cry for a long time. I talk to my mother twice a day, and am amused every time how amazed she is that we can video chat over the mobile phone," Mohammed says. "I hope to meet her again one day."

or register to post a comment.