"You helped building up Germany -- You have enriched our country, economically, but above all humanly! Your hard work, your passion and your humanity have made our country what it is today. For this I am deeply grateful to you, who are with us today as representatives of the first generation..."

With the recruitment agreement, which was signed with Turkey on October 30, 1961, not only Turks but also members of the minorities arrived in Germany. Thus, in the course of the opening of job opportunities abroad, the first groups of Assyrians, mainly from the city of Midyat, arrived in Germany.

Assyrians of different Christian denominations lived mainly in southeast, Turkey, especially in the districts of Tur Abdin, Mardin, Sirnak and Hakkari, in a region that was a restricted area for foreigners to enter until the early 1960s. Life was marked by insecurity and discrimination due to the unfavorable legal status as a non-Turkish and non-Muslim minority. Added to this was the difficult economic and social situation in the region.

Until the 1960s, Midyat was the only city in Turkey with a majorly Christian population. Midyat had a strong tradition of craftsmanship and trade. It provided the entire region with important services; at a young age, most young people began to learn a craft profession. Not all craftsmen were able to establish an own business of find permanent employment opportunity in Midyat to support their families. The younger generation dreamed of a better life and often did not want to continue their family's traditional agricultural work. Some moved to Istanbul or other Turkish cities in the west of the country to find work. My father, for example, gave up tailor workshop and worked since the late 1950s for US companies in Turkey who owned government licenses for drilling for oil, gas and water.

Germany had a special appeal to Assyrians, not only because of its reputation for quality products, but also because it was considered a Christian country. When Germany and several European countries began to recruit guest workers from Turkey, including Austria (from 1964), Holland (1964) and France (1965), many Assyrians saw this as an opportunity to come to Europe. This process of migration, triggered by domestic and foreign policy circumstances (such as the Cyprus crisis or the Kurdish conflict), continued in several waves and over several decades until the end of the 1990s.

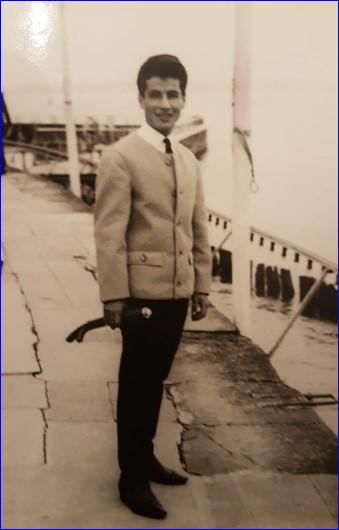

Assyrian Work Migrant Pioneers

The very first Assyrian who came to Germany in the course of the recruitment agreement in 1961 from Midyat was Alexander Maksiye. The 84-year-old lives with his family in the city of Wurzburg. He is officially one of the very first 45 people recruited from Turkey to Germany in 1961 in context of the agreement. He was specially honored for this 2011 in the city of Wurzburg during the commemoration of anniversary of the agreement. His life story was even presented in a short stage play at the Wurzburg's City Theater.

With his support, his three brothers Habib, Johann and Sait followed him to Germany in 1962 and 1963. Johann, meanwhile 78 years old and grandfather, lives in his retirement in Wurzburg too. In our conversation about the early times in Germany, he told me that "Alexander, as a young man in Istanbul in 1961, worked for his cousin as a tailor; there he learned about the recruitment agreement between Germany and Turkey from the newspaper."

In Istanbul and other cities in Turkey, there were large advertising campaigns for the agreement with Germany. Posters and advertisements in newspapers announced that Germany was looking for skilled workers. Interested people had to apply to the local employment agency (Isci Bulma Kurumu), undergo an aptitude test if they did not have the necessary qualifications, and pass a health examination. The latter was performed by a German doctor accompanied by an interpreter in Istanbul.

Johann also tells me that Alexander "immediately went to the employment agency in Istanbul and filled an application to come to Germany and work as a tailor. At the employment office, however, he was told that they were looking for carpenters in Germany."

As it happens, Alexander Maksiye had a small carpenter's workshop in Midyat, knew the profession and thus had the qualification. He applied as a carpenter and, after completing his papers, passport and health examination, travelled to Stimpfach, a small town of 2500 south of Crailsheim in southern Germany.

After a year Alexander moved to Aalen in Baden-Wurttemberg, south of Crailsheim, about thirty minutes from Stimpfach, to work as a tailor in his dream job. There was the main factory of the Greiff-Werke. It was one of the well-known German manufacturers of men's and industrial clothing at the time, founded after the Second World War.

In 1962, Alexander initiated an invitation (work assurance) from the German company to his then 17-year-old brother Johann, who was still learning the tailor profession in Midyat. Johann made his way to Istanbul to take care of the necessary papers to leave for Germany.

When I arrived in Istanbul, my cousin, who had been living and working in Istanbul for some time, helped me with the formalities. At the passport office I was told that as a minor I could not get a passport without my parents' permission. I wrote a letter to my father in Midyat to send me an officially certified permission. This took several months; during that time, I worked as a tailor to earn my living expenses.I had the invitation from the Greiff-Werke in Aalen, which confirmed that I could work for them as an apprentice. Therefore, I did not have to go through the procedure of the Turkish Employment Agency, nor did I have to go for a health check.

Finally, in February, I was able to complete my documents and board the train to Germany at the Istanbul's Sirkeci Train Station. The journey to Germany on the Orient Express, at that time the locomotive was coal driven, took two days. The route led via Bulgaria, former Yugoslavia, and Austria to Munich. Arriving in Munich on a Sunday, February 28th, I changed the train to Ulm in order to travel from there to Aalen/Wurttemberg, my final destination.

People who arrived via the Isci Bulma Kurumu were received by a German team in Munich and got guidance and support to get to their destinations.

"When I arrived in Aalen, I was surprised that my brother was not waiting for me at the train station, because I had sent him a letter about my arrival before my trip." It turned out that Johann's letter had not yet arrived from Istanbul.

Other Assyrians joining from Midyat

The group of Assyrian men from Midyat in Aalen grew over the next few years. In addition, my own father, Ibrahim, came to Aalen in the middle of the 1960s with other friends, most of whom also worked as tailors at the Greiff-Werke. According to Johann, the Assyrian group made up about a quarter of the 40 or so workers from Turkey who were employed at Greiff-Werke, most of whom were women.

During the holiday season in the summer months, many traveled back to Midyat to visit their families; others used the opportunity to get married. Through marriage and family reunification, the first small diaspora community of people originating from Midyat came into being in Aalen. In the course of family reunification in 1967, my own family settled in Aalen too. My younger sister and myself were the only Assyrian children in Aalen at that time. We were immediately registered by my father to schools nearby in Aalen. It was no coincidence that the group in Aalen came from the same quarter of Midyat and were most of them related to each other.

A few years later Alexander and his brothers, Ishak Mourike and Iskender Turker, moved to Wurzburg, a city in northern Bavaria, as did my family in 1969. Most members of the Aalen group continued to work for a subsidiary of the Greiff-Werke in the region and used to live with their families until early the 1970s in the same apartment complex.

According to Johann Maksiye, in the mid-1960s there were in total about 35 Assyrians from Midyat working in different countries in Europe, among them Austria, Holland and Switzerland; Johann knew most of their names. One can speak of them as the pioneers of migrant workers to Germany.

The residence permit for guest workers coming from Turkey was initially limited to two years. Accordingly, the employment contracts had to be also limited. In the sense of a rotation principle, the foreign workers were supposed to return home and be replaced by new workers. In contrast to Germany's other recruitment agreements with Italy or Spain, there was no provision for family reunification for the workers recruited from Turkey initially.

However, the principle of rotation could not be maintained in the long run. German companies particularly spoke out against letting semi-skilled workers leave after two years. A new version of the Agreement with Turkey, dated May 19, 1964, repealed the principle of rotation; the ban on family reunification was also lifted.

Shortly after the start of the oil crisis in 1973, the then German Social Democrats-led government under Willi Brandt decided to stop further recruitment, which affected all recruitment countries. Until then, according to official statistics, nearly 800,000 (680,002 men and 150,000 women) people from Turkey were living in Germany.

In 1973 the Assyrian community living in and around the city of Wurzburg and originating from Midyat and villages of Tur Abdin grew to nearly 50 Assyrian families.

or register to post a comment.