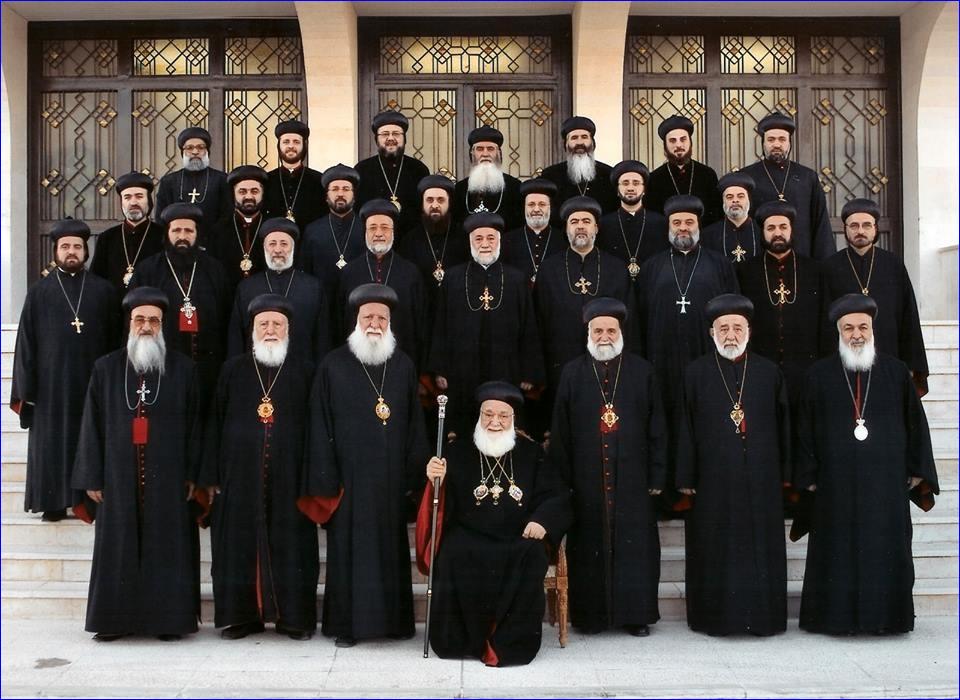

The Syrian Orthodox Church is split into two rival factions. One wing is anti-Assyrian and hides behind an "Aramean" identity and has gained an increasing foothold in the Church. The other faction rejects any ethnic imprint on the Church, Aramean or Assyrian. A bitter feud over the new patriarch is expected. The main actors are the bishops who are entitled to vote at the synod which will elect a new patriarch, but behind the scenes different interests are at work, such as the Ba'ath regime in Syria and the Turkish government, who is keen to move the Patriarchal See from Damascus back to the Zafaran Monastery in Mardin, Turkey.

Hostile regimes in the Middle East have always attempted to infiltrate the Assyrian churches, with varying degrees of success, since they have great power over their respective parishes. The goal is of course to alienate the Assyrians from their ethnic identity and make them identity themselves as Christian Arabs, Christian Turks or Christian Kurds. The Barzani clan in northern Iraq is the latest among the actors using this strategy, but the Kurds have no direct influence over the Syrian Orthodox Church, unlike the Baathist regime in Syria and the Turkish government.

Different bishops have probably already started plans to take over the patriarch's office and an intense power struggle behind the scenes is what we can expect. The church and its congregations are already divided into two main factions, as a result of the deceased patriarch's policy of forming new and competing archdioceses. The actors in this power struggle are using the name conflict among the Assyrian people as an instrument of their power ambitions. The "Aramean" side is claiming that bishops and parishes that do not support them are followers of the Assyrian side. The Aramean faction's clergy openly attack the Assyrian movement both in their preaching and in various anti-Assyrian media. Bishops who support an "Aramean" identity and their parishioners are happy to cooperate with various hostile forces to change everything named Assyrian to Aramean -- perhaps soon even the church's name as well. This anti-Assyrian faction equates the Assyrian word suraya1 (meaning Assyrian) with "Aramean" and displays the so-called "Aramean" flag on church premises and on its roof in many places in the world.

This may be the start of a split within the Syrian Orthodox Church. Even a hundred years ago a group in India left the Church to protest against the patriarch's actions. The Assyrian Professor Ashur Yousef criticized Patriarch's policy in strong terms in an article in 1914. Before that, the Syrian Catholic Church broke from the Syrian Orthodox Church. The most famous split occurred in the end of 14th century when city of Turabdin, Turkey formed its own patriarchate. In 1839, nearly 500 years later, they would reunite under the same patriarch.

No faction among the bishops to elect a new patriarch will want to settle for half the cake -- it will fight for the whole. But if it can't succeed a split may become a reality. The new patriarch will be very important for the Assyrian nation. If he remains neutral and focuses on managing the internal affairs of the Church, there will be harmony. An anti-Assyrian patriarch will increase tensions within the community.

The experience of the last three patriarchs shows that even if a bishop is an Assyrian patriot he may change sides and become an opponent of the Assyrian national movement. Before we get into potential candidates, it is useful briefly review the three previous Patriarchs.

In January 1933 Bishop Afrem Barsom was elected in his diocese in the city of Homs in Syria, which was then a French Mandate. Thirteen years earlier, he had demanded a free Assyria at the Paris Peace Conference. But the Great Powers who won the First World War betrayed all their promises and Bishop Barsom was deeply disappointed. The Patriarchal See had now move from the Zafaran monastery in Mardin to Homs as the new Patriarch was no longer welcomed in Turkey. He had confronted Turkish representatives about the Assyrian genocide, Seyfo, and was declared by Turks a persona non grata. He eventually began to cooperate with the Arab nationalists in Syria to drive France out of the country. 1946 Syria became independent. As patriarch Afrem Barsom hoped that the remaining Assyrians who had survived the genocide would find peace and safety in the Arab country of Syria.

His later transformation was stunning. He no longer spoke in terms of an independent Assyria, but became an anti-Assyrian of the first degree. He began a smear campaign against the Assyrian name. He claimed afterwards that Assyrian was synonymous with Nestorian (Eastern Assyrians) and asserted that it was the British who had given the name Assyrian to the Nestorians of Hakkari, Turkey2. Even today anti-Assyrians in Sweden and other countries claim the term Assyrian applies only to the Eastern Assyrians. In March, 1920 Bishop Barsom met with Lady Surma, the sister of the Eastern Assyrian Patriarch, in London and said that "our people had come a step closer to unity." But in 1947 he issued a patriarchal decree forbidding his congregation from cooperating with Nestorians "because Nestorius was still banned."

In December 1952 Patriarch Barsom ordered the three churches in the United States, which he himself had consecrated in 1927-1928, to change the name Assyrian Orthodox Church to Syrian Orthodox Church. This created major tensions and conflicts among Western Assyrians in the United States. In recent years, two of those churches were renamed to Syrian or Syriac, but the third is registered as a foundation that prohibits changing its name. Thus there is now a single Syrian Orthodox church in the world which in English is called Assyrian Orthodox Church. It is located in Paramus, New Jersey.

1957 Barsom was succeeded of Patriarch Yakub III. The Assyrian patriot bishop Dolabani held the synod's opening speech and gave his support to Bishop Yakub, who won by just one vote. The other candidate, Boulos Behnam, was one of the most educated bishops in church history, but Dolabani preferred bishop Yakub because he was considered to be an Assyrian patriot. Four years earlier bishop Yakub had written a book about the history of the church in which he said in the preface that the church nationally belongs to Assyrians and Arameans who had given the civilization to the world. But as patriarch he soon began acting against the Assyrian national movement and in 1977 he nearly banished Assyrian leaders in Sweden.

Patriarch Zakka Iwas took office in September 1980 and promised to introduce more democracy in the church. His predecessor was known as a dictator. Patriarch Zakka introduced a system in which each bishop had a free hand to take care of his diocese in the best way. This was abused by bishops Cicek and Abboudi in Europe. They created major conflicts among the Assyrians when they refused to perform religious services to members of Assyrian Associations. The patriarch had probably no involvement in this.

Another struggle for power within the leadership of the Church in Sweden led to the patriarch contributing to a brand new division within the church. Bishop Abboudi had been driven away from Sweden when the church's central board published tape recordings revealing incriminating information about him. He was succeeded by Bishop Abdullahad Gallo Shabo in 1987.

But in 1990 a new power struggle flared up when Bishop Shabo demanded transparency in the church's finances. That led to his banishment from the church. He gathered around him members who were unhappy with absolutism in church governance, and managed to remain in Sweden. Several delegations of bishops visited Sweden and met with both sides to report to the patriarch. The general opinion of all who had followed the development was the Patriarch would take action against the civil church council which had driven out its bishop. There were also rumors that the old church board planned to join a splinter group in India. It is said that the board also had purchased an ambulance as a gift for those in India. But the decision by the patriarch was not forthcoming. Meanwhile, Bishop Shabo's opponents became directly subject to the Patriarch. After a few years Patriarch Zakka decided to appoint a new bishop to the old board and in February 1996 the split was sealed when Bishop Benyamen Atas became known as patriarchal deputy. Since then there have been two distinct camps within the same church with their own bishops. Both are registered as Syrian Orthodox Church, but one side uses the name Syrianska Orthodox Church on their church buildings. The two episcopals are located just steps away from each other in the town of Sodertalje, Sweden. The system of two or more episcopates soon spread to other countries.

Patriarch Zakka's contribution to the church was thus a permanent division. Another split occurred in California after the bishop of the Western United States, Augin Kaplan (my old teacher at Zafaran seminary) had banned the local priest Joseph Tarzi. Father Tarzi and 350 Assyrian families left the church and joined the secessionists in India. The reason was that they criticized Bishop Kaplan for his involvement in a financial scandal involving millions of dollars. He had borrowed money from the church and the congregation to bring home a fictitious legacy of 30 million dollars from Nigeria. In fact, he was tricked by the Nigerian mafia and then tried to borrow even more money to complete the legal proceedings he had initiated against the Mafia. He also pulled Bishop Cicek into the affair and Assyrians in Europe borrowed large sums with Bishop Cicek as guarantor for the loan. Bishop Cicek was also forced to mortgage his own residence and the monastery of St. Afrem in Holland as collateral for the bank loans for "Project Nigeria." Eventually all the money was lost without a trace. It is likely that not only Nigerians but also people within the Syrian Orthodox Church leadership got a piece of the pie. Cicek was about to reveal the whole hoax, but he died mysteriously in a hotel at the airport in Dusseldorf, Germany, in 2005.

I mention this to illustrate patriarch Zakka's action (or inaction) that contributed to the church needlessly losing the priest Joseph Tarzi and 350 Assyrian families.

The reason why Patriarch Zakka created divisions within his church may well have been a deliberate policy of divide and conquer. It is also likely the Baathist regime in Syria had a big hand in it. The same applies to the old dictator Saddam Hussein, whose regime had a large hand in various Assyrian churches. For Patriarch Zakka, this meant also economic benefits. Observers suspect that he was bribed when he agreed to consecrate a new bishop for the opponents of bishop Shabo in Sweden.

And now we are faced with the choice of a successor to Patriarch Zakka. The political situation in Syria, however, is chaotic because of the ongoing civil war. We do not know how much power the Assad regime has over the Syrian Orthodox Church nowadays. Before the war the regime prepared the next patriarch through systematic planning. He would be from Syria, preferably directly linked to the country's security, Mukhabarat. Several bishops, priests and monks were recruited or trained by the Mukhabarat, as well as numerous civilian agents among Assyrians in Sweden and other parts of the world. But now the situation is completely changed. Almost all bishops who had dioceses in Syria are out of contention. Aleppo's Bishop Yuhanna Brahim was kidnapped and most probably murdered. He was the number one candidate for the patriarchal position. The bishop of Jazeera, Matta Rohem, fled when he was needed most to Austria and left his diocese. The bishop of Homs has almost no community left, the town has been nearly emptied of its Christian population and several churches have been bombed.

Bishop George Saliba in Mount Lebanon has long been regarded as a rival candidate to Yuhanna Brahim, but he may not have health on his side. Many Assyrians see Bishop George as favorite but we must remember, as I said earlier, those favorites that have turned. Bishop Samuel Aktas in Turabdin is another favorite. He is strongly rejected by the Turkish government because of his courageous stance against the government in the confiscation of St. Gabriel Monastery's land. The favorite Bishop of the Turks is Yusuf Cetin in Istanbul, who in recent years has become a megaphone for Prime Minister Erdogan's policies. Turkish representatives have previously mentioned Bishop Saliba zmen in Mardin as a potential candidate and demanded that the Patriarch See be brought "home" to the Zafaran monastery. But he's apparently not one who sells his identity and has likely been removed from Erdogan's list. There is a fourth bishop of Turkey, namely in the city of Adiyaman. His name is Malke Urek and was my old classmate at the seminary at Zafaran. He is an aggressive anti-Assyrian. He sent a protest letter to the Parliament of Austria when a few years ago it acknowledged that Seyfo, the World War One Turkish genocide of Assyrians, as a genocide. But instead of thanking Parliament for the genocide recognition, he attacked it for using the name Assyrian instead of "Aramean."

There are a number of other bishops with Turkish citizenships abroad, but as I said we do not know which regimes and interests have the greatest influence over them. In India, the church has a large number of bishops and over two million members in Kerala, but the patriarch's seat has never before gone to an Indian bishop.

According to various reports, the Patriarch Zakka will be buried at the Sednaya cave outside Damascus on Friday, March 28. It seems the security situation is stable enough to hold this event in Damascus, even for the synod to be held there. In all probability, the Assad regime will do its best to make everything happen under the regime's supervision, despite all the difficulties the regime and the country is facing. But it might go against the regime's plans, as it did when Patriarch Zakka was elected. At that time the regime tried to elect a candidate from Syria, but Bishop Quryakus of Hassake tricked the Mukhabarat, Syria's intelligence service, by bringing to the synod meeting an Iraqi citizen, Sanharib Iwas, who was elected as Patriarch Zakka.

This time it's not just a question of citizenship that is important. There are divisions between the two rival factions of bishops so deep that they may well result in the division of the church and the election of two patriarchs, an "Aramean" Syrian Orthodox and traditional Syrian Orthodox. As to the Assyrian movement it has always set the unity of the church and the nation at the forefront, but the power-hungry anti-Assyrians will stop at nothing for their own purposes and may well divide the church if the new Patriarch is not their candidate.

1 In Assyrian it is written as asoraya, the initial 'a' is silent. Asoraya means Assyrian.

2 Editor's note: There is no such thing as "Arameans" today. Assyrians who call themselves "Arameans" do so under the influence of Turkish and Syrian governments.

See the following:

The Terms "Assyria" And "Syria" Again

Assyria and Syria: Synonyms

Assyrian Identity In Ancient Times And Today

Akkadian Words in Modern Assyrian

or register to post a comment.