Aydin is one of the last remaining Christian Assyrians in Hah, known in Turkish as Anitli, a village perched in the historic Tur Abdin region near the town of Medyad (Midyat). While many residents left decades ago, driven by conflict, economic hardship, and systematic pressure, he chose to stay. His decision is not rooted in nostalgia alone. It is an act of preservation. "I stay because the language stays," he says in Sahit (The Witness), a 2023 documentary directed by Ahmet Kiliç that chronicles the slow disappearance of Assyrian life from the region. The film, recently made available on YouTube, centers on Aydin as both narrator and subject, a quiet figure standing against the erosion of cultural memory.

Assyrians are among the oldest indigenous peoples of Beth Nahrin (Mesopotamia), tracing their presence in the region back thousands of years. For centuries, Tur Abdin, encompassing parts of today's Mardin Province, served as a spiritual and cultural heartland, dotted with monasteries, churches, and villages where Assyrian, belonging to the Aramaic language family, was spoken as a living language. Today, that landscape is largely emptied of its original inhabitants.

Hah itself carries deep symbolic weight. Known among Assyrians as a "place of rest," the village hosts some of the region's most ancient Christian landmarks, including Mor Sobo Church and churches dating to the fourth and fifth centuries. One structure is believed to have been among the earliest monuments built explicitly for Christian worship, later converted into what is now the Church of the Virgin Mary.

Yet history has not guaranteed continuity. After decades of forced migration, only about 20 Assyrian families remain in the village, most sustaining themselves through agriculture and animal husbandry. The language that once echoed naturally through homes and courtyards now survives largely through deliberate effort.

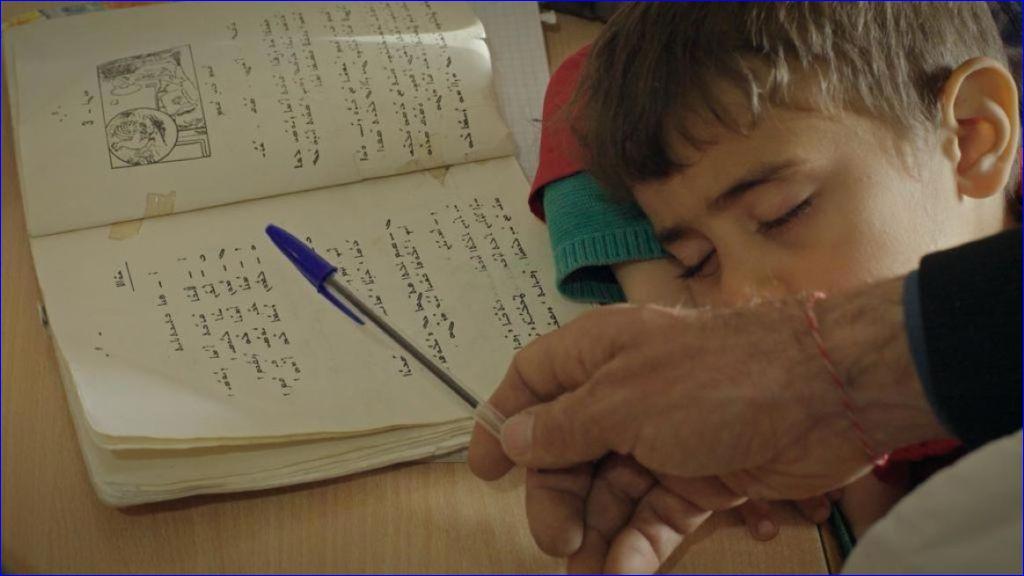

Aydin works as a Assyrian language teacher, instructing children who might otherwise grow up without access to their ancestral tongue. Paradoxically, many elders in the region no longer speak Assyrian fluently, having adopted Kurdish or Turkish under social and political pressure. Aydin himself grew up speaking Kurdish with his parents, learning Assyrian later, a reversal of generational transmission that underscores the fragility of the language.

In Sahit, he is less an activist than an observer. He speaks of people who have died, buildings that have crumbled, seasons that pass unchanged. The film's title reflects this role. "Witness," as Kiliç explains to Agos journalist Marta Sömek, refers not only to human memory but to the land itself, the stones, the churches, the abandoned homes that silently record what has been lost.

Kiliç, who grew up in nearby Kfarboran (Dargeçit), said the idea for the documentary emerged from a personal reckoning. "I learned that Dargeçit was entirely built by Assyrians," he said. "And now there is not a single Assyrian person left there. That absence disturbed me."

Rather than relying on academic commentary, the director chose to build the film around one man's lived experience. "It could have been a professor explaining history," he said. "But hearing it from someone who resists disappearance by simply continuing to live, that mattered more."

Filmed over five days in 2023, the documentary captures Hah in shifting weather, from harsh sun to sudden hail, a visual metaphor for endurance amid instability. Since its completion, Sahit has been screened at human rights and documentary festivals in Merde (Mardin), Istanbul, and Adana, drawing emotional responses from audiences. Some viewers, Kiliç said, left in tears.

The director resists labeling the film as narrowly communal. "This is not only a Assyrian story," he said. "It is about anyone who has felt erased, overlooked, or pushed to the margins."

In Hah, that sense of erasure is palpable. And yet, so is persistence. Each Assyrian lesson Aydin teaches, each word spoken deliberately in a language once forbidden or discouraged, becomes a small act of defiance.

"I am a witness," he says in the film, not as a declaration, but as a fact. Thus, in a region where history is often rewritten through absence, bearing witness may be the most enduring form of resistance.

or register to post a comment.