Weathered building façades, a few undergoing renovative works and most with their ground level covered in graffiti, radiate a sense of abandonment. The liveliness of the community, however, is betrayed by the prevalence of small shops and informal gatherings on park benches and entryway stairs.

The slow speech of elderly residents, the sharp rhythm of Arabic echoing from cafés and barbershops, the lilt of Balkan dialects, and the occasional trumpeting of English, both native, and broken, piece together a mosaic of change, of the old and new.

Only a few streets away is the city's famed "Square of Tolerance" -- the Bulgarian Orthodox Saint Nedelya Cathedral, Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Joseph, Central Sofia Synagogue, and Banya Bashi Mosque all within sight of one another.

Their proximity speaks of the invisible threads that tie together centuries of faith, exile, and return. From antiquity to the present day, Sofia, and Bulgaria as a whole, has been a crossroads.

Within this multi-cultural enclave -- and walking distance of a kosher Algerian cafe, Kurdish bakery, and Arab grocer -- you can find Ashurbanipal.

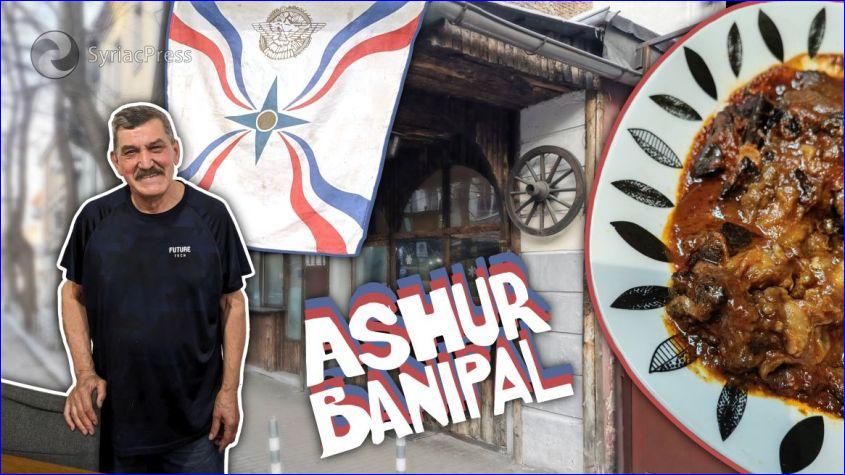

Given its namesake, the last great king of Neo-Assyria Empire, Ashurbanipal, one would imagine a grand, ostentatious dining hall covered in gold and azure stone. On the contrary, Ashurbanipal appears unassuming from the outside. Almost hidden in plain sight, the building is modest with simple signage and an old-world feel. Its understated presence contributes to its charm -- an almost clandestine gem.

The interior is compact and unpretentious. Service is informal. You order at a small counter, picking up your dishes as they're finished. What defines Ashurbanipal is chef and owner Frederick Benjamin, who goes by Freddy.

Years ago, Freddy ran another restaurant near the Women's Market. After closing it, he opened several shawarma shops and, in the meantime, completed a chef's course in Bulgarian cuisine. He used to work alongside Bulgarian chefs in a traditional local restaurant but ultimately returned to his original ambition of opening his own establishment, cooking the food he grew up with. That vision became reality with the opening of Ashurbanipal in early 2013.

Freddy speaks of his path, and of his adoptive Bulgaria, with a combination of affection and matter-of-factness. "I am Frederick from Iraq. I am Assyrian," he says. "I settled in this country, Bulgaria, over 25 years ago. I have a wife and two children here." Freddy's wife, Linda Awanis, is the founder and current chairperson of the Council of Refugee Women in Bulgaria.

"I think life here is something else," Freddy says with a fondness. "Many times, I had a chance to go to other European countries. Maybe for other people, it was great to go somewhere else, like Germany or the Scandinavian countries. But I like this country."

He explains that Bulgaria's Assyrian community is exceedingly small. "We have just three, four families here. This is the only Assyrian restaurant in the country." Yet he insists he has always felt welcomed. "People here are very sympathetic and kind. They accept us as much as we accept them. I discovered this when I started working in Bulgaria and started cooking here."

An engineer by training and an Arabic calligraphist by trade, Freddy came to be a chef by a twist of fate. "Cooking saved my life," Freddy says frankly. During the Iran--Iraq War, from 1980 to 1988, he served as a soldier. "I was a cook in the Iraqi Army. I am living today because my role as a cook kept me away from the fighting."

He is originally from Baghdad and, despite his clear affection for Iraq, he says he no longer returns. "There is no purpose."

"I like my mother country, for sure," he explains. "But I think it is useless going there. Even though I love Iraq, I am living in Bulgaria. I feel like a Bulgarian. If you don't like your first country, you will never like your second one." He has now been in Bulgaria for nearly three decades. "More than 25 years," he says with a laugh. "Sometimes I feel more like a Bulgarian than the Bulgarians."

His life now is rooted in a village just outside Sofia, a place he describes with warmth. "We are like a small family there. We also have a small taverna in the village. We cook for one another, drink together. I often make doner kebabs for the children." Then he laughs and adds, "It's good to have a new mother."

Freddy says Bulgarians have embraced Iraqi cuisine with curiosity and openness. "Bulgaria is a crossroads, they are open to new tastes. Chinese, Indian, Arabian. When we started with Iraqi dishes, it was something different, but they liked it. There is an interest."

Over the years his restaurant has been featured on television and YouTube, and he has cooked with the organization MultiKulti at primary schools. "One time we taught eight classes, forty-fifty kids each. The second we finished, a new group would come in," he recalls, laughing. "I was begging the organizer for a break. I took a short break and when I came back, all the children were waiting and chanting 'Freddy! Freddy!'"

As for the restaurant's name, he says it came from a desire to honor the culture he comes from. "The name of the restaurant is Ashurbanipal because we are Assyrians. I am Assyrian."

Freddy pauses for a moment, as if reflecting on his past and his identity. "Our language is not Arabic, it is not Kurdish, it is Aramaic," he eventually says. "We have a nation, but we have no country. We've been forced to fight for others, targeted by others, and now many have left Iraq. In, maybe, 15 years, 20 years, there may be no Christians left. Assyrians are peaceful. We are Christians. Perhaps this has made it easy to push us out of our homeland."

At the end of our conversation, and after we've finished our meal and settled the bill, Freddy makes sure we get a picture of him with the Assyrian national flag, hanging in Ashurbanipal since it first opened.

or register to post a comment.