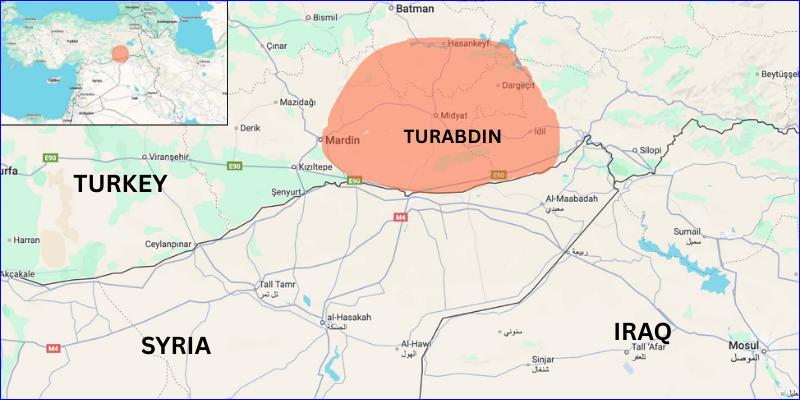

The body that manages state-owned real estate is the Milli Emlak Genel Müdürlüğü (National Real Estate General Directorate), commonly referred to as the Hazina. When state surveyors from the Hazina arrived in the mostly empty Assyrian villages, they ended up classifying much of the surrounding lands as public property, often formally designated as forest land. According to Turkish law, land that has not been in use for a certain number of years and is not actively claimed by someone often becomes registered as public land. Individuals who object to the surveyors' decision, typically posted publicly at the local municipality, have ten years to raise objections. However, as Assyrians had largely left the region and returning was considered unsafe for many years, most such registrations went unchallenged. The result: vast areas originally owned by Assyrian families became state property.

But the issue has another layer of complexity as well. In some cases, the surveyors seem to have been intentionally misled by locals about the ownership of different parcels. As the surveyors do not know the area, they usually rely on locals for information about who owns what. There are examples where individuals who disliked a family (and whose members were no longer living in the village) would intentionally tell the surveyors that their parcel belonged to someone else. In other instances Kurds who had moved in to the Assyrian villages would falsely claim that they own a certain piece of land in the hope to have it registered in their name so they later can try to sell it to the Assyrian owners for a hefty price.

The magnitude of the mess created by the land registry process in Tur Abdin has become increasingly apparent. In recent years, as political and security conditions have improved, a growing number of Assyrians returning to their villages have discovered that lands held by their families for generations has been either converted into public land, registered on someone else or, in some cases, that it has even been sold to others.

Two examples

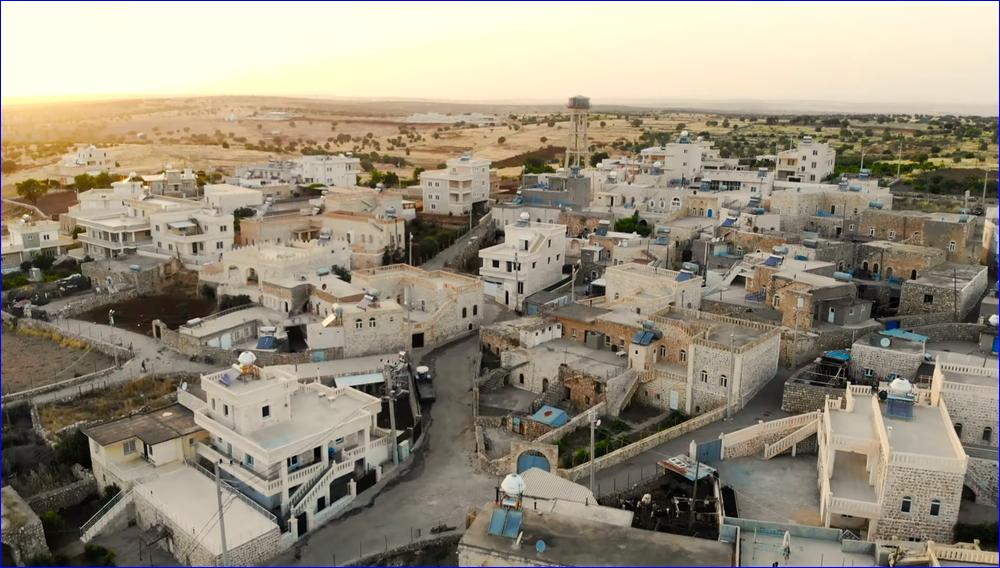

In November of this year, four plots surrounding the village of Arkah, a purely Assyrian village with around 400 permanent residents, were announced for sale by the Hazina. The plots had belonged to an Assyrian family from the village but, like many other lands surrounding Assyrian villages, had been registered as Hazina property after decades of abandonment. The announcement alarmed villagers, as the original owners were not yet in a position to repurchase the plots, meaning non-Assyrians, usually Kurds, could potentially buy them.

The villagers reached out to the authorities who soon announced that Hazina-owned parcels in Arkah and surrounding areas would not be allowed for sale for a certain period. The four previously listed fields were removed from the sales list, and the corresponding tenders were canceled.

There was a similar situation a few years ago in another Assyrian village, but in that case the size of the plots was much bigger and they had already been put up for sale and sold to non-Assyrians before anyone could intervene. Despite the odds, community leaders were successful in convincing the authorities to annul the sale of the lands and reclaim them.

The goodwill of the Turkish authorities has helped the local Assyrians to remedy several similar situations so far. But despite recent successes in halting such sales, Assyrians find themselves facing a constant race against the clock to monitor similar plots being put up for sale by the Hazina. Once a tender is announced, the community must either ensure that the original owning family, often living abroad, repurchases it, or lobby authorities to postpone or cancel the sale entirely.

Assyrian leaders are increasingly aware of the stakes, particularly the potential demographic impact if lands fall into non-Assyrian hands. Meanwhile, Swedish-based Assyrian lawyer Ilhan Aydin, together with other prominent Assyrians, is working on a political solution to resolve the Hazina land issue permanently.

-- "We have to be realistic and realize that ultimately we cannot buy back all the lands that have passed to the Hazina. This needs a political solution," he said in an interview earlier this year with Assyria TV.

According to Aydin, Assyrians have an argument to present to Turkish authorities: the Tur Abdin situation should be treated as a special case, as Assyrians were effectively afraid to return and claim their lands for decades due to the lack of security circumstances.

While some focus on a political solution, other Assyrians continue to monitor everyday land issues to salvage as much as possible.

or register to post a comment.