Too often, historical narratives of hardship overlook women's crucial role in keeping together family and community and in preserving their cultural and religious traditions.

That's the case no longer for four figures from modern Middle Eastern history who have been given new life by UD student researchers.

"We wanted to give them their due," said senior history and French double major Erin Pinto, who used digital tools to perform basic translations of text from Aramaic and Arabic to English in pursuit of their stories.

Thanks to $2 million in research grants from the United States Agency for International Development, assistant professor Alda Benjamen and her partner organizations are helping conserve and share the cultural heritage of Iraq's minority communities. Through this work, students discover the power of digital humanities in capturing complex cultural narratives at risk of being lost and gain deeper understanding of the Middle East beyond its portrayal as a conflict zone.

"We're preserving the coexistence and pluralism that was in Iraq," Benjamen said.

Born and raised in Kirkuk, an oil-rich region of Iraq claimed by the Kurdish people and the Iraqi government since the late 20th century, Benjamen remembers the colorful and cultured reality of her daily childhood.

In classrooms, students learned the Ba'ath party's nationalist history in Arabic, but on playgrounds and streets, they switched effortlessly between Turkish, Aramaic and Kurdish as Assyrian Christians played with Muslim Kurds and

Turkmen.

Benjamen's early influences included her grandmother. Born in 1918, she was a teacher and principal who spoke Aramaic, Arabic, Turkish, French and English. Children would gather close to hear her stories. Benjamen recalls one about a Jewish family who lived nearby when her grandmother was young.

"I sometimes wonder why she did that," said Benjamen, who traces her professional interest in oral histories to her grandmother. "Was it just that she was a storyteller? She had no interest in politics at all, but now, I wonder and I reflect, did her stories have a deeper purpose? Yes -- to teach us about Iraq's coexistence that included the Jewish community, which of course is no longer there."

People resist suppression of identities that the state and its education system tried to enforce, Benjamen said, through such seemingly mundane practices. These unofficial histories, the ones on which culture and religion are built, are important but difficult to preserve.

Benjamen, who moved to Toronto after the first Gulf War, has been doing fieldwork on the minority cultural communities of Iraq since 2007. In addition to textual heritage, including manuscripts, books and photos, she began relying on intangible histories, including stories, songs and prayers, and invited families to share their private collections with her.

As a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pennsylvania Museum and the Smithsonian Institution, Benjamen worked on a National Science Foundation-funded project to document the Islamic State group's destruction of cultural artifacts and sites from 2016 to 2018 in Northern Iraq.

"That got me engaged in the world of cultural heritage," she said.

Benjamen then brought archives from California's Assyrian immigrant community -- a people indigenous to Mesopotamia -- into the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, where she was a fellow in the Department of History and the Center for Middle Eastern Studies.

That project coincided with her first USAID grant with the Antiquities Coalition and four Iraq-based organizations to digitize cultural records and build the capacity of local teams to safeguard and uphold Christian and Yezidi heritage in Iraq.

Under the current grant extension, Benjamen and a dozen UD students worked with preservationists in Iraq to document, digitize and catalog manuscripts that date back to the fourth century, along with thousands of photos from the 1800s and 1900s, and other incorporeal and oral heritage. Last spring, students enrolled in a three-credit virtual internship course, Preservation and Digitization of Iraqi Cultural Heritage. They explored the historical context and challenges faced by Iraq's minority communities while gaining insights into the principles of cultural heritage preservation and digitization, referred to as the field of digital humanities.

International studies major Yasmin Nassar and María Gómez '24, who majored in history, researched the vibrant culture of the Yezidi community, an ethnoreligious group indigenous to the region of Mesopotamia, in partnership with Sinjar Academy.

Delos Peñas-Johnson '24, who double majored in international studies and Spanish, and Robert Smart, a business economics major, compiled data to make the case for donor support for the nonprofit Assyrian Aid Society by highlighting the educational successes of Assyrian-language students.

History majors Ted Vignocchi and Kate Shryock cataloged photos and created a digital exhibit about modernity in the Mosul region for the Chaldean Catholic Diocese of Mosul's Centre Numérique des Manuscrits Orientaux.

Women's voices are important -- but hard to find in official documentation. That's why the Syriac Heritage Museum in Erbil, Iraq, teamed up with the fourth team of students taking Benjamen's internship course.

Pinto and senior history major Charlotte Capuano spent long days at Roesch Library searching for academic research on women identified by the museum. When they found a reference, it was usually a single mention in a long book -- and then they'd chase down the source only to discover it was in a language they did not know. They'd attempt a rough translation of the journal title so they could decide if the content would be relevant. Often, it was not.

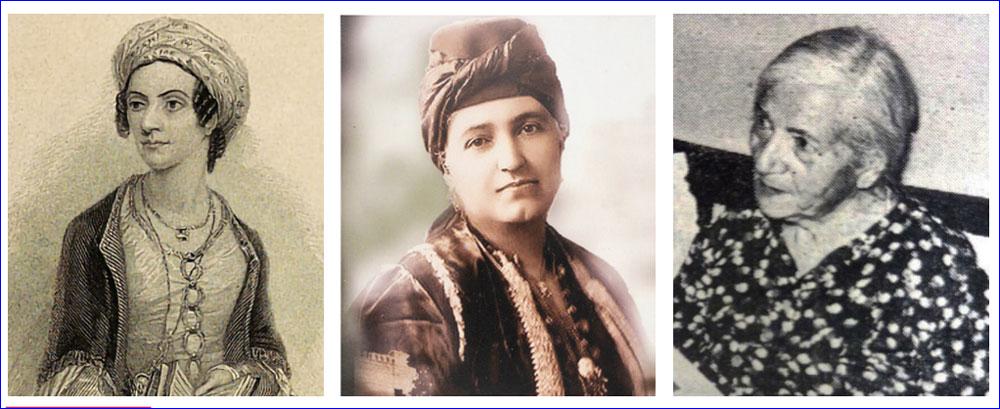

That's when they had a breakthrough. Sitting on Pinto's couch, Capuano ran a photo the museum provided through Google's reverse image search, Google Lens. Up came information on Lillie Taimoorazy (1900-1992), known as the queen of modern Assyrian heritage. They had been searching for an improper spelling of her name translated into English.

"And we were off to the races," Pinto said.

On YouTube they found music credited to Taimoorazy and a video of her speaking. They also discovered a relative of Taimoorazy's living in Chicago who is active in the Assyrian community.

Benjamen arranged Zoom interviews between the students and the relative. The relative asked, "What do you want?" Answered Capuano, "Everything, everything, anything you can give us."

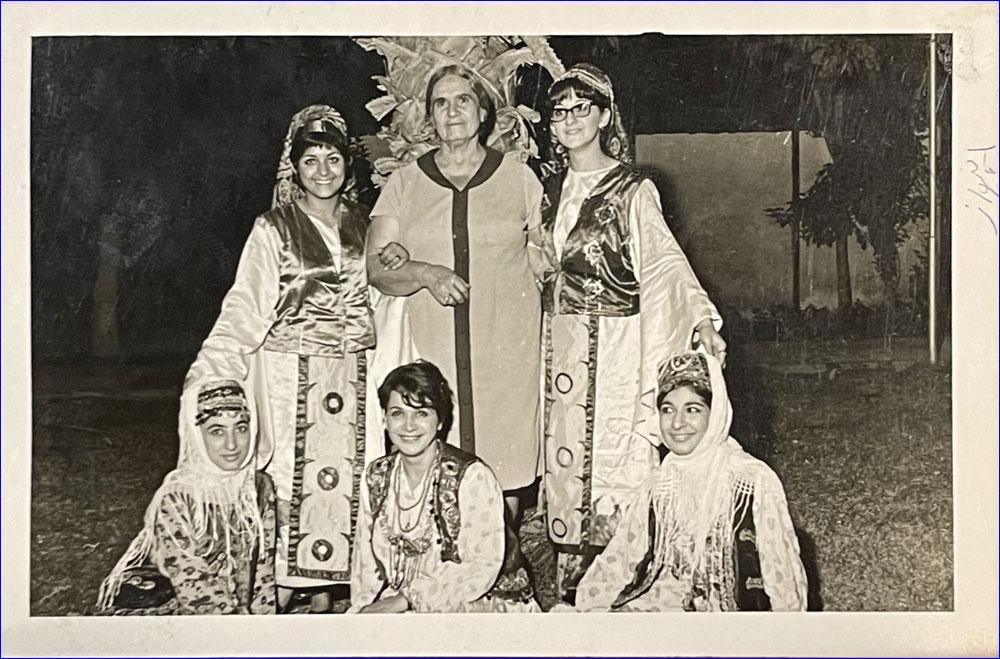

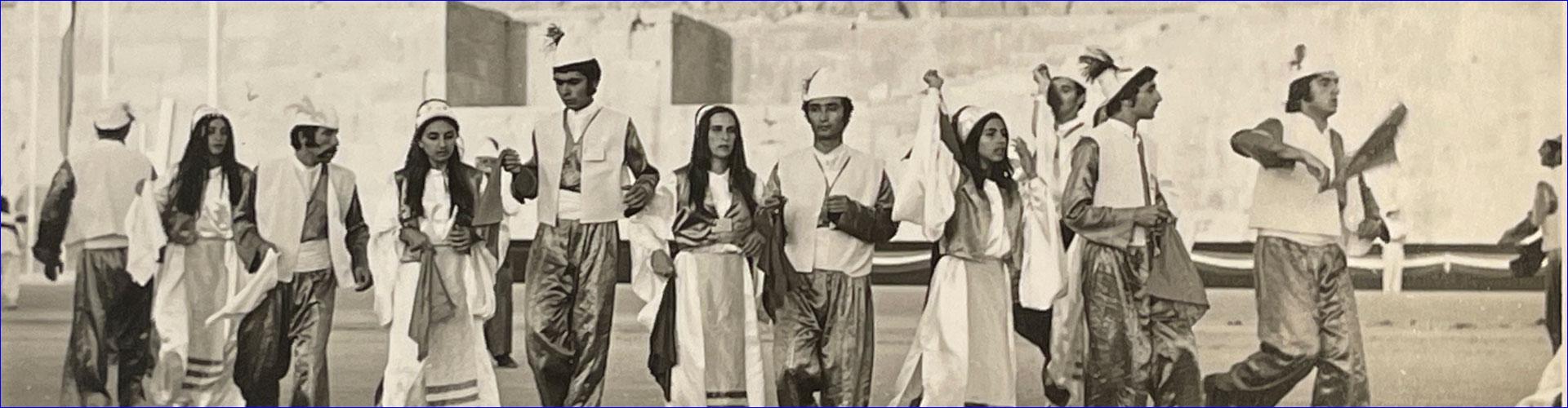

The relative shared stories and held up historical documents from the family's personal archive to the computer's camera: Taimoorazy's academic degrees, yellowing parchments with official stamps and fading signatures penned in ink two generations ago; black and white photos of dancers in billowy costumes from the Shameeram Folkloric Group that Taimoorazy founded in 1957. Taimoorazy came to life before the students' eyes in a way they never imagined.

Pinto and Capuano also created digital histories of three other women: Maria Theresa Asmar (1804-1870), who traveled to many countries while growing in her Chaldean Catholic faith; Surma Khanum (1883-1975), a leader in the Assyrian Christian community who was passionate about peace; and Maryam Nerma (1890-1972), a feminist and journalist who founded the newspaper The Arab Girl.

Impressed, the museum wanted more. Capuano and Pinto received a Dean's Summer Fellowship from the College of Arts and Sciences to refine their digital presentation with the help of two University librarians, associate professor Ben Daigle and assistant professor Liz Grauel.

The students also collaborated with the museum on a physical exhibit. The students wrote the text for the displays -- and then rewrote them, in consultation with Benjamen, curators and other scholars so the text could be translated from English into Aramaic, Arabic and Kurdish. The museum's physical display included a recreation of a traditional dance costume Taimoorazy would have worn, accompanied by music she wrote, plus stories and artifacts the relative had shared with Pinto and Capuano.

The exhibition, which was displayed in Iraq in July, protects cultural heritage for the future and shares the story of northern Iraq's vibrant Christian community through the struggles and achievements of Middle Eastern women, the museum said, thanks to the efforts of the University of Dayton.

When history comes to life through sound, photos, maps and other digital artifacts, it has the opportunity for a wider impact through the internet.

"I took a history careers class ... and we talked about digital humanities a lot, because it is a new field and people are really excited about it," Capuano said. "Being able to do something with it, especially as an undergrad, is amazing."

All four teams in the original internship course used the online tool StoryMaps, assisted by the University's librarians. Digital humanities can keep whole documents that could crumble -- or be intentionally destroyed by those wanting to erase a people from their home.

Her students are doing important work, Benjamen said, because history can illuminate how people can chart a common path forward.

"We learn ... how do communities negotiate? How do they come together and coexist? When are they marginalized? Why are they marginalized? And history does repeat itself, so we understand more about ourselves by understanding the past."

Students will get more opportunities to help in the spring semester, when Benjamen will teach a similar course. She has applied for another extension of the USAID grant, and she is working on her next book.

Capuano is continuing her research on the four women, turning her work into a senior capstone paper. Pinto also found their examination of the past enlightening. "I want to work with museums in some way, which was not a thing I had known a year ago," she said.

While the students were giving the historical women of Iraq their due, they also helped chart their own path for their futures.

Additional reporting for this story came from Dave Larsen and Lauren McCarty '26.

or register to post a comment.