Related:

By Foot To China: Mission of The Church of the East, to 1400

Nestorian Monument In China

The Nestorian Monument Of Hsian Fu In Shen-Hsi, China

The Story of a Stele - China's Nestorian Monument and Its Reception in the West, 1625-1916

The Christian community in Tang China managed to survive for as long as the emperors were tolerant of other religions. That changed during the rule of the emperor Wuzong (841-846 CE), who banned all foreign religions.

The Tang Dynasty: China's Golden Age

After a long period of disunity and civil war between northern and southern states, China was reunified into a single state once again during the Sui Dynasty Period (581-617). Emperor Wendi (581-604) managed to restore the kingdom's bureaucratic apparatus and centralize the state that he ruled from the rebuilt city of Cnag'an. The construction of the Great Canal from 605 to 609 CE united the Empire economically.

Although the Sui Dynasty ruled for a short period of time, it laid the foundation for the power and prosperity that China experienced during the Tang Dynasty. The Sui Dynasty's rule came to an end with the revolt against the emperor Yangdi (604-617) because of his unpopular and unsuccessful wars against Korea. General Li Yuan, who led the revolt, took the throne and ruled by the name of Emperor Gaozu (618-626). With his rule, the Tang Era began.

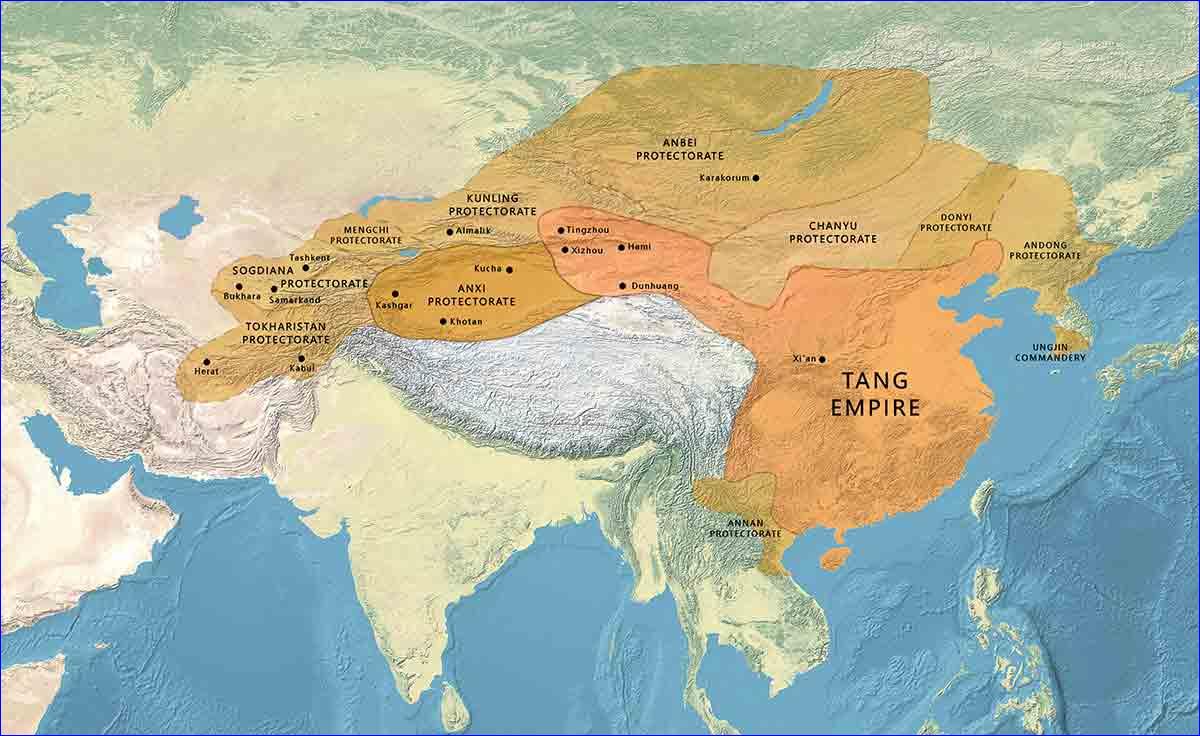

During the reigns of his successors, Taizong (626-649) and Gaozong (649-683), China's territory was greatly expanded. Through a series of successful wars against Turkic tribes to the east, they established control over the Silk Road.

Trade with other Asian countries expanded through both land and maritime routes. Thanks to this expansion of trade, during the early Tang Period, China entered an era of economic, social, and cultural prosperity. A great number of foreigners came to China, mostly from neighboring countries but also from other parts of Asia. They settled in big trading cities and towns and were mostly engaged in business, but they also influenced China's cultural life during this period.

Various forms of cultural activity bloomed during this period of peace and prosperity, such as art, poetry, and fashion. The capital city of Cnang'an became the residence of many artists, such as Zhang Xuan (c. 713-755). Tang China also served as a model for other Asian countries and their dynasties, such as Korea and Japan. They looked to Tang Dynasty rulers in order to use their experiences to strengthen their states.

Early Tang emperors, like their Sui predecessors, promoted Buddhism, which became an integral part of the Chinese state and society. A great number of Buddhist temples flourished throughout the country, which positively affected the development of both the culture and the economy. However, the promotion of Buddhism did not mean rejection of traditional Chinese religions, such as Confucianism and Taoism, which still played an important role in society.

In times of peace, emperors tolerated other religions that found their way into China during this period. In the capital city of Chang'an, members of various other religious groups lived and thrived, such as Zoroastrians, Muslims, and Manichaeans. Under the early Tang emperors, China became a multicultural and cosmopolitan empire. Such circumstances enabled Christians to find their place among other religions in China at that time.

The Church of the East: Early History and Expansion

In order to better understand the history of Christians in China, we need to look at the history of the church to which those Christians belonged. To do that, we need to look back a few centuries. The Church of the East is an ancient church that has its origins in ancient Persia. Christianity appeared in Persia in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, during the Parthian Empire. It is not known exactly how Christianity spread into Persia. One possibility is that it was done by Greek-speaking refugees from the Roman Empire who fled persecution.

According to Medieval Historian, Wilhelm Baum, the earliest Christians emerged from Jewish communities in Persia. Aside from them, early Christians in Persia included local Persians, Arab tribes, and the Aramaic-speaking population, who made up the majority of Christians in that period.

In the second half of the 3rd century CE, Persian Christians had developed an episcopal structure of their own. At the beginning of the 4th century CE, the bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon managed to impose supremacy over all other bishops. This marked the beginning of the Church of the East.

With the rise of the Sasanian Empire during the 3rd century CE, Zoroastrianism was declared the official state religion. Because of that, Christians faced persecution from time to time during the 4th century CE. The situation changed again during the rule of the Yazdegerd I (399-424).

In the first half of the 5th century CE, the Church of the East established its organization, headed by the Bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon. It gradually distanced itself from the Church of the Roman Empire and declared its independence in 424. However, at the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 410, the Church of the East accepted the teachings proclaimed at the First Ecumenical Council in 325. The decisions of the Council of Ephesus in 431, which condemned the Patriarch of Constantinople, Nestorius, were not accepted. Nestorius thought that the title "Theotokos" (Mother of God), given to the Virgin Mary, was not appropriate and that only the title "Christotokos" (Mother of Christ) could be applied. The Church of the East did not participate in any other ecumenical councils after this.

Because of this, the Church of the East was, and still is, wrongly described as "Nestorian." The Christology of the Church of the East was created under the influence of Theodore of Mopsuestia, a representative of the Antiochian school. Members of this school of thought considered that there were two separate natures in Jesus Christ. This was different from the official dogma of the Church in the Roman Empire, according to which the two natures of Jesus Christ were united.

During the 5th and 6th centuries CE, the Church of the East spread throughout the lands controlled by the Sasanian Empire and Christians became a significant religious minority. During the 6th century CE, monasticism spread, and many new monasteries were built.

When Byzantine-Sasanian wars broke out, Christians in Persia faced persecution again. However, thanks to capable patriarchs such as Mar Abba I the Great (540-552), the Church of the East managed to survive and thrive.

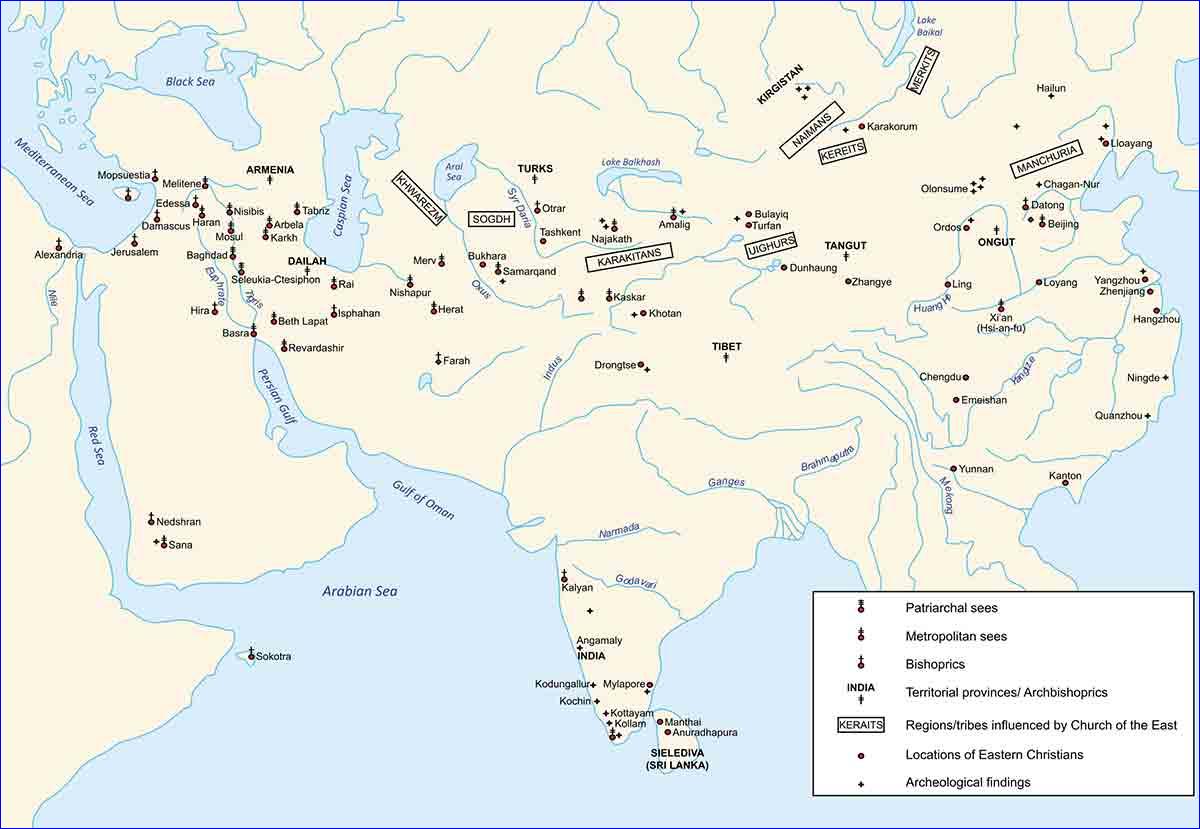

During this period, the Church of the East spread beyond the borders of the Sasanian Empire, among the Arab tribes, in Central Asia, and even as far away as India and Sri Lanka. The church even survived the Arab conquests of the 7th century CE. During the rule of the Muslim Caliphs, the Church of the East belonged to the ahl-al-dhimma, that is, religious groups that, in exchange for religious freedom, paid tribute to the state.

A Golden Age of Christianity in China

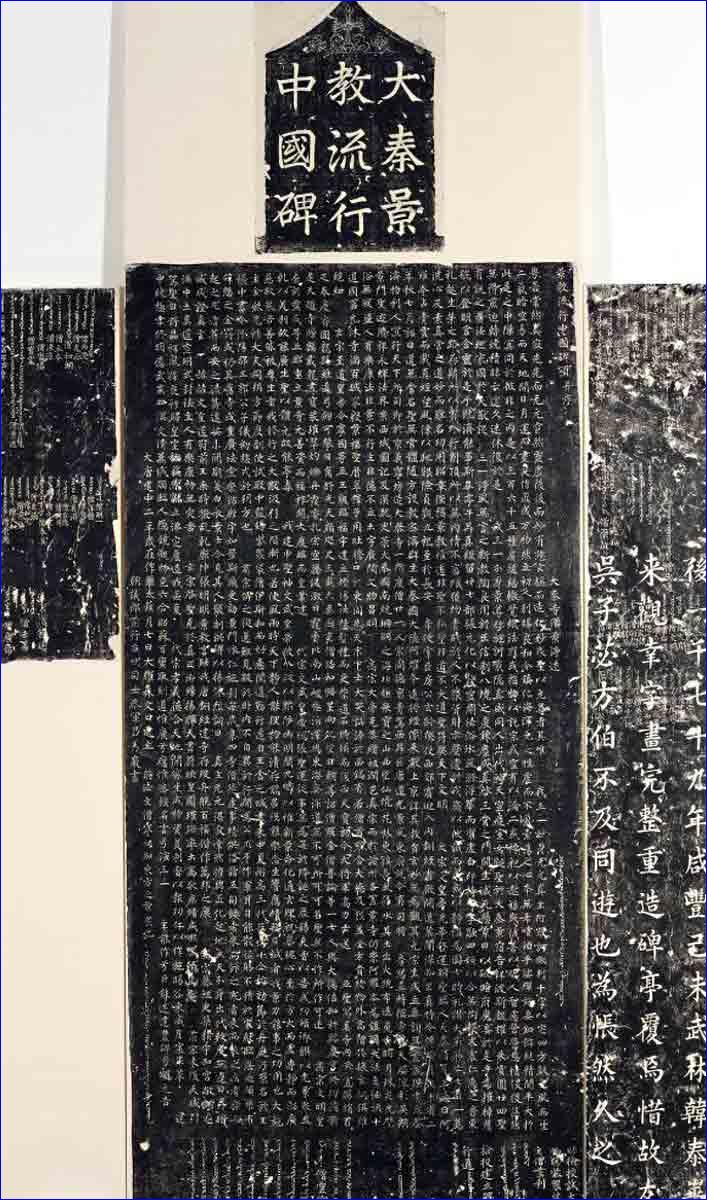

For many years, very little was known about the history of Christianity in China until the arrival of missionaries from Europe. That changed with the discovery of the so-called "Nestorian Stele" in the city of Xian in the early 17th century. This stele, 2.79 meters high (9 ft 2 inches) and 99 centimeters (39 inches) wide, was erected in 781 CE and is inscribed in Chinese script with a few lines at the end written in Syriac.

The author of the text was the monk Adam, with the Chinese name Qing-Qing. The Xian Stele tells us about the arrival of Christian missionaries from Syria to China during the reign of Emperor Taizong (626-649). At the head of this mission was the Syrian monk Alopen (or Olopen), who came to Chang'an in 635 and presented the Christian holy books to the emperor. This was followed by the imperial edict of 638, which allowed Christian missionary activity in the country. A Christian monastery was immediately built in Chang'an where 21 monks could live.

According to the emperor's orders, the Christian holy books presented to him by Alopen were translated and stored in the imperial library. Alopen was most likely part of an official mission from the Sasanian Empire as an official representative of the last Sasanian ruler, Yazdegerd III (632-651). His son, Peroz III, was in exile in China after the Arab conquests. Peroz was responsible for the construction of another Christian monastery in 677 CE. In Chinese documents, Christian monasteries are called "Ta-qin monasteries." "Ta-qin" was the Chinese name for the Roman Empire or the Middle East, depending on the context.

During the decades that followed, Christianity continued to flourish in China. It enjoyed the support of Taizong's successor, Gaozong (649-683), and many important people in the empire. According to the Xian Stele, Gaozong allowed Christian churches and monasteries to be built in every province of the empire. This does not necessarily mean that monasteries were built in every province, but it is a good indicator of the spread of Christianity in China during that period.

In addition to the central parts of China, Christianity spread to the surrounding countries, to Tibet, and among the Uyghurs. The Church in China was officially organized as the Metropolitan Province of Beth Sinaye under the patriarch Saliba (714-728).

Some Christian priests managed to reach important positions and served as advisors or even generals. For example, general Issu was the right hand of Lord Guo Ziyi. Issu was a priest of Iranian origin. His real name was Yazdebod, and he served as a general, who protected the northern borders of the empire. He was a great benefactor of Christian communities, and his name stands out on the Xian Stele.

Art and Literature

Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

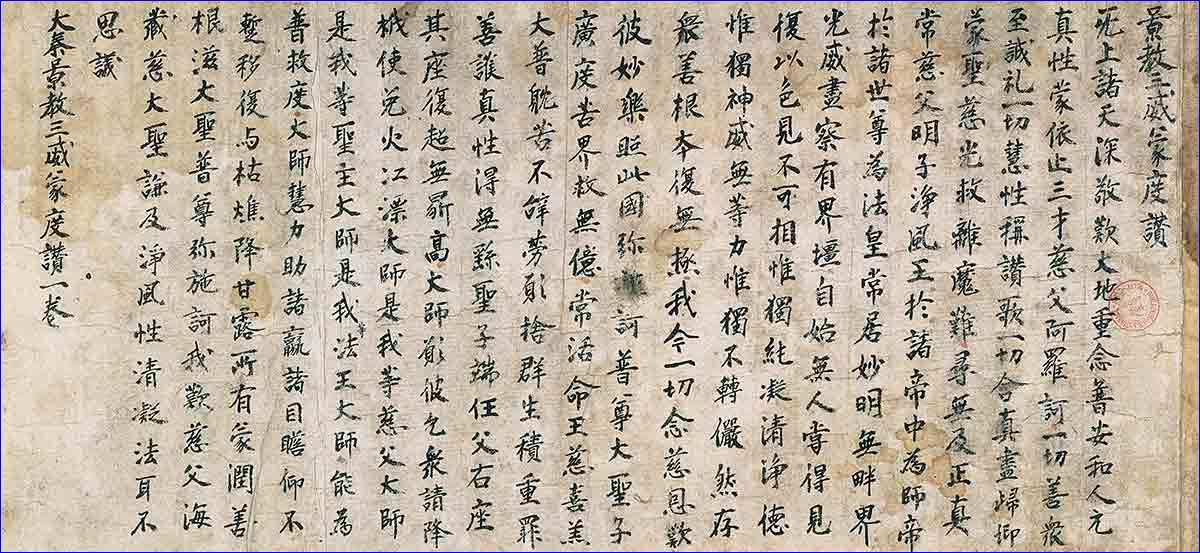

The history of Christianity in Tang China spans two centuries, and a small number of Christian texts in Chinese have survived to this day. Christian monks and priests carried out a great deal of effort in the translation of Christian texts into Chinese. During the 780s CE, an Indian scholar named Pradschna resided in China. He helped a monk named Adam, whose Chinese name was Qinq-Qing, translate Christian texts. By the end of the 10th century, around 500 texts had been translated into Chinese, including the complete New Testament and part of the Old Testament.

Out of these 500 texts, only a handful have survived to this day. Among them, the oldest ones are the Book of Jesus, the Messiah, and On the One God. They were written in 635-638, and 641 CE, possibly by Alopen. A memorial pillar from Luoyang, erected in 814/815 CE, contains the text titled Teaching on the Origin of Origins of the Da Qin Luminous Religion. Aside from that, another pillar contains the epitaph of a Sogdian Christian woman, and it is decorated with pictures of a cross and winged angels.

Some other Chinese Christian texts that have survived to this day include the Book of Praise (presumably written by Qing-Qing in the late 8th century), the Book of Venerable Men and Sacred Books (written in c. 906-1036), and the Book of the Origin of the Enlightening Religion of Ta Qin (written before 1036).

In addition to these texts, some remnants of Chinese Christian art have survived. A silk painting of a haloed Christian figure, dating from the 9th century, was found in the Mogao Caves. A painted male figure is represented with a halo and a winged crown containing a cross. The position of his right hand is taken from Buddhism, and it symbolizes the explanation of a doctrine. The silk painting depicts either Jesus Christ or a saint.

At the beginning of the 20th century, three frescoes were found in the remains of the Christian temple in Kocho, two of which have been preserved. The first one possibly depicts a celebration of Palm Sunday. The fresco depicts a man of Middle Eastern origin, most likely a deacon or priest, in front of three believers. According to another interpretation, it depicts a ceremonial greeting inspired by Buddhism. The second fresco depicts the Repentance and is smaller than the previous one. The third fresco, lost today, once depicted the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem.

Persecutions and Demise

Discovery of Civilizations of Central Asia)

Discovery of Civilizations of Central Asia)

At the end of the 8th century, the Christian community in China reached its zenith. However, most believers came from foreign populations: Iranians, Sogdians, Turks, and Uyghurs. Very few Chinese converted to Christianity because it was still a foreign religion to them.

According to Baum, during the middle of the 9th century, there were about 260,000 Christians in China. The survival of Christians in China depended too much on the goodwill of emperors and local rulers. While peace reigned and the emperors promoted religious tolerance, Christians lived in peace. In turbulent times, however, rulers often turned against foreigners and foreign religions.

Christians experienced the first persecutions in China during the reign of Empress Wu (683-705). As a fanatical Buddhist, she elevated Buddhism to the level of the state religion in 691 and turned on members of other religions, including Christians. During her domination of the state, several monasteries were looted and burned. The persecutions ended during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong I (713-756).

Christians experienced their final downfall during the reign of Wuzong (841-846). He was a traditional Taoist and turned against all religions that he considered foreign. First, in 843, he banned the practice of Manichaeism, and later his persecutions were extended to other religions, even Buddhism. His edict from 845 banned "Persian religions," namely Zoroastrianism and Christianity. All members of these religious groups were ordered to leave China.

During the next century, Christians perished in China completely. With the fall of the Tang Dynasty in 907, China once again entered a period of civil war and internal instability. Because of this, trade routes with the West collapsed, and the remaining Christians lost contact with their patriarch.

Around 980, patriarch Abdisho I sent six monks to China to examine the situation. They reported that Christianity had completely disappeared in China. Churches and monasteries were destroyed, and there was only one Christian left. This, however, did not mark the end of Christianity in China. It would be revived in the 13th century, during the reign of the Yuan dynasty.

or register to post a comment.