Vatican Media)

Vatican Media)

Truth to be told, Catholics sometimes succumb to this bipolar thinking too. And while there obviously are consequences from the choice of one leader over another, what sometimes gets overlooked is the vast range of things which fall into the category of institutional commitments, and therefore are not really dependent upon whoever happens to be in office at a given moment.

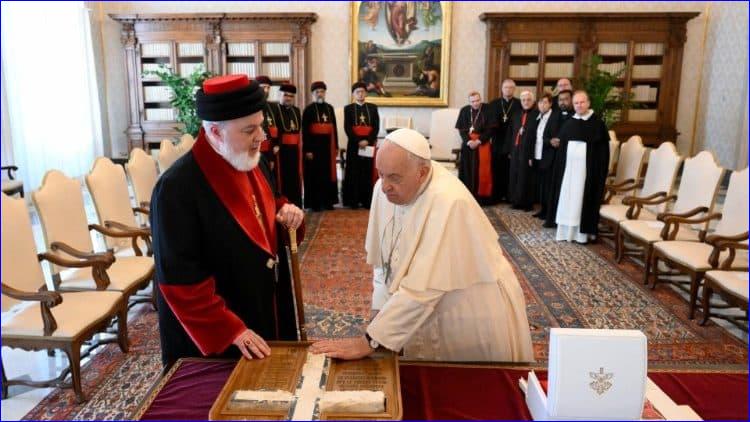

A good reminder of the point came Saturday, when Pope Francis welcomed Mar Awa III, Catholicos-Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East, which is not in communion with Rome or anybody else, to the Vatican, along with members of a mixed commission for dialogue between the two churches.

Assyrians, members of an ethnic group traditionally concentrated in Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Iran, were among the earliest converts to Christianity, and have remained committed to the faith despite almost two millennia of hardship, persecution, and forced dislocation. Today, membership in the Assyrian Church of the East is estimated at around 400,000, giving it roughly the same following as the Catholic Diocese of Green Bay, Wisconsin -- proof, among other things, that in ecumenical relations, size really doesn't matter.

Headquartered in the Ankawa neighborhood of Erbil in Iraq, the Assyrian Church of the East has been active in the modern ecumenical movement for some time, including its 40-year journey with the Catholic Church.

A high point came in 1994, when then-Patriarch Dinkha IV traveled to Rome to meet Pope John Paul II, and the two leaders signed a common Christological declaration announcing that despite verbal differences over Christology dating to the 5th Century, the two churches now recognize each other's faith as valid.

Pausing for a moment to let that sink in, the significance actually is extraordinary.

Before the rupture of the Oriental Orthodox Churches in 451 over the Council of Chalcedon, before the Great Schism between East and West in 1054, before the Protestant Reformation in 1517, the first breach in Christianity came in 431 when the ancient Church of the East rejected the conclusions of the Council of Ephesus and specifically its endorsement of the term Theotokos, or "Mother of God," for Mary, insisting, in keeping with the doctrine of Nestorius, that Mary instead should be termed the Christotokos, "Mother of Christ."

The 1994 common declaration, for all intents and purposes, declared that original schism in the Christian world resolved, an act of healing 1,500 years in the making.

Almost as breathtaking, seven years later the Vatican issued a document entitled "Guidelines for Admission to the Eucharist between the Chaldean Church and the Assyrian Church of the East." (The Chaldean Catholic Church originated in the 16th century, when a portion of the Church of the East decided to enter into communion with Rome.)

Though issued by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christianity Unity, the document came with the agreement of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, headed at the time by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, and also with the personal approval of Pope John Paul II.

In essence, the document stipulated that when faithful from the Church of the East cannot attended Mass in their own tradition, they can take part in a Chaldean Catholic Mass and receive communion, and vice-versa for Catholics at a Mass of the Church of the East. This recognition of the validity of the Assyrian Mass came despite the fact that its Eucharistic Prayer, the Anaphora of Addai and Mari, does not contain the Institution Narrative (the portion of the prayer that contains the lines, "This is my body" and "This is my blood.")

It was a fairly stunning decision, given that Catholic theology had long regarded the Institutional Narrative as an absolutely necessary condition for the validity of the Mass -- the 15th century Council of Florence, for example, referred to the words of the Institution Narrative as the "form of this sacrament."

The late Jesuit Father Robert Taft, one of Catholicism's leading experts on eastern liturgies, declared the 2001 guidelines as "the most remarkable Catholic magisterial document since Vatican II." By treating consecration as something accomplished by the entire liturgical prayer, and not by an isolated set of "magic words," Taft believed the Vatican had repudiated a quasi-mechanistic understanding of the sacrament that "seriously warped popular Catholic understanding of the Eucharist."

All this, let us recall, came with the express endorsement of two popes -- the sitting pontiff at the time, John Paul II, and the future Pope Benedict XVI.

The thrust toward reconciliation has continued under Pope Francis, with a common declaration in 2017 on sacramental life and a document in 2022 on images of the church in the two traditions. During the visit by Mar Awa III this week, Francis also announced that he was adding St. Isaac of Nineveh, also known as St. Isaac the Syrian, to the Roman Martyrology. He was a seventh century bishop in the Church of the East, celebrated for his spiritual writings, and long venerated as a saint in the Assyrian tradition.

Now, Catholicism has recognized him as a saint as well.

(While rare, the gesture is not unprecedented. In 2023, Pope Francis added 21 Coptic Orthodox martyrs to Catholicism's register of saints. The 21 men, mostly from Egypt, were beheaded by ISIS on a beach in Libya in 2015.)

What all of this means is that through three election cycles in Catholicism -- conclaves that brought John Paul II, Benedict XVI and Francis to the papacy -- not to mention the same number of transitions in Assyrian Patriarchs, the commitment to détente between Ankawa and Rome has remained intact, and that's hardly the only element of continuity. It's simply the one that happens to be on clear display right now.

Sure, it matters who's in charge, both in Catholicism and in secular politics. Just recall that no matter how despondent or elated you may feel about the outcome of any particular vote, it's never as glorious or as awful as it seems in the moment -- because while personalities come and go, institutions and their interests endure.

or register to post a comment.