Wikimedia Commons)

Wikimedia Commons)

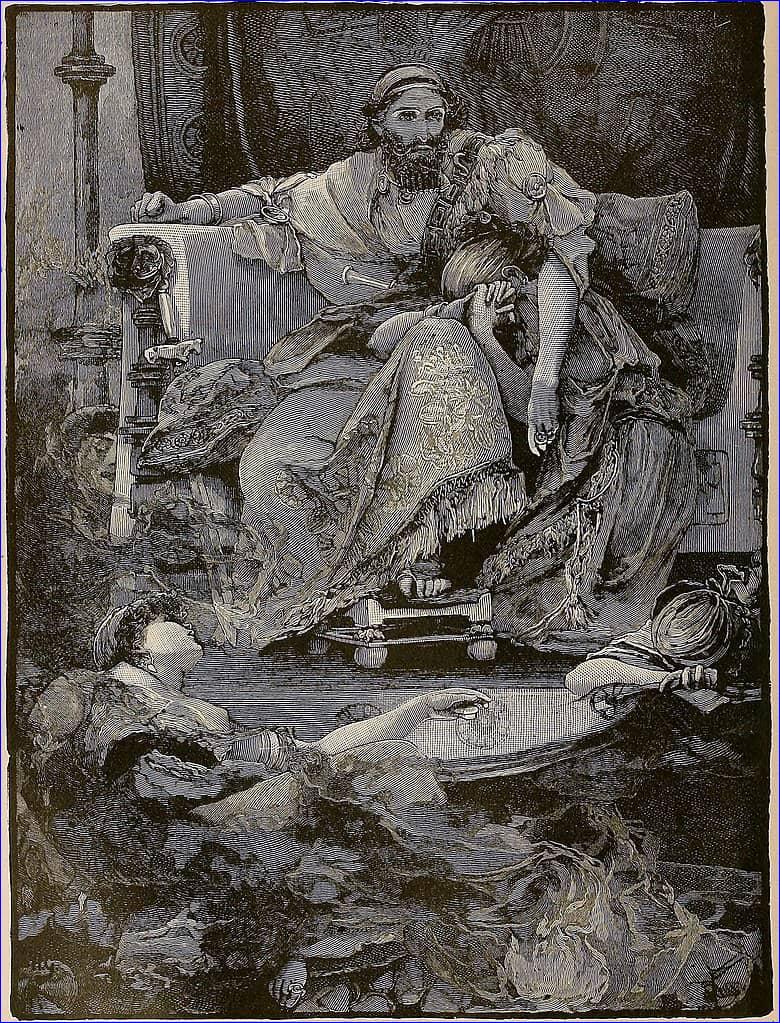

Probably Delacroix is the author who has reached the broadest audience in this sense, thanks to his painting The Death of Sardanapalus. He painted this work--housed in the Louvre--in 1827, causing a stir due to the feverish combination of violence and sadism it displays, as well as the strange use of color (warm tones, with a predominance of red), the free brushstrokes that emphasize the sense of movement, and an original asymmetric perspective. Delacroix himself had to explain its content when he first exhibited it at the Paris Salon:

The rebels besieged his palace... Lying on a magnificent bed atop an immense pyre, Sardanapalus orders his eunuchs and palace officials to slaughter his women, his pages, even his favorite horses and dogs; none of the objects that had served his pleasures were to survive.

That painting, a symbol of Romanticism, was too daring for its time and was therefore poorly received. However, in 1830, it inspired Hector Berlioz to compose a cantata on the same theme, and in 1845, Franz Liszt for his opera Sardanapalus; curiously, both pieces were left unfinished, with the first even destroyed by its author, leaving only a fragment of a few minutes. Delacroix himself took the idea for the painting from Sardanapalus, a verse tragedy published in 1821 by Lord Byron, who dedicated it to his friend Goethe, inducing him to include an allusion to the character through Mephistopheles in the second part of Faust.

Wikimedia Commons)

Wikimedia Commons)

Byron, in turn, used Dio Cassius' Roman History as a source, where a parallel is drawn between Sardanapalus and Elagabalus. Therefore, as we can see, the turbulent Assyrian monarch had already attracted the attention of classical authors: Lucian of Samosata devotes the second chapter of Dialogues of the Dead to him, alongside other figures such as kings Midas and Croesus, the philosopher Menippus of Gadara, and the god Pluto; even Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, compares him to those who have a life view centered solely on the pursuit of pleasure:

Most men, if we are to judge them as they appear, are true slaves, choosing for pleasure a life fit for beasts, and what gives them some reason and seems to justify them is that most of those in power only use it to indulge in excesses worthy of a Sardanapalus.

It was almost inevitable, then, that Dante would give him a place among the long list of characters that appear in his Divine Comedy; specifically, in the chapter dedicated to Paradise: "Sardanapalus had not yet shown what can be done in a bedroom". Other writers included references to Sardanapalus in their works, always in that negative tone: Molière in Don Juan, Charles Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities, Henry David Thoreau in Walden, Maxim Gorky in The Lower Depths, Henri Gougaud in The Angel's Laughter... It is also interesting to note the special interest composers had in him, for apart from those already mentioned, operas were also dedicated to him by Giovanni Domenico Freschi, Christian Ludwig Boxberg, Giulio Alary, Victorin de Joncières, Victor-Alphonse Duvernoy, Otto Bach, and Alexander Sergeievitch Famintzin, while Benjamin Wilhelm Mayer composed an overture.

Wikimedia Commons)

Wikimedia Commons)

But what about the historians? Around 395 B.C., Ctesias of Cnidus wrote two books, Persica and Babyloniaca, in which he seems to identify Sardanapalus with Ashurbanipal for the first time. These texts have been lost, and we only know of them second-hand, primarily through Diodorus of Sicily, who in his Historical Library says:

Sardanapalus, the thirteenth successor of Ninus, who founded the empire, and the last king of the Assyrians, surpassed all his predecessors in luxury and effeminacy. Never seen by any man outside the palace, he lived the life of a woman and spent his days in the company of his concubines, spinning purple cloth and working the softest wool. He dressed in women's clothes and covered his face and entire body with creams and whitening ointments used by courtiers, which made him more delicate than any courtesan. He made sure his voice was feminine during drinking sessions, so that he could enjoy the pleasures of love with both men and women. In such excess of luxury, sensual pleasure, and shameless temperance, he composed a funeral hymn and ordered his successors to inscribe it on his tomb after his death, a hymn composed in a foreign language and later translated by a Greek. [...] His ambivalent nature not only caused him to die dishonorably, but also brought about the total destruction of the Assyrian Empire, which had lasted longer than any other state in history.

Wikimedia Commons)

Wikimedia Commons)

That depravity of the monarch, Diodorus continues, would have led to the fall of Nineveh after a long siege imposed by an alliance of Medes, Persians, and Babylonians. At the last moment, Sardanapalus ordered a great pyre to be lit, into which he threw his concubines and eunuchs, then immolated himself along with "all his gold, silver, and royal garments". In his Epitome of Pompeius Trogus' "Philippic Histories", Justin confirms this view and the end:

The last ruler of the Assyrians was Sardanapalus, a man more effeminate than a woman. One of his prefects, named Arbaces, who governed the Medes, had, after much effort, managed to see him, a privilege hardly ever granted before. He found Sardanapalus surrounded by a crowd of concubines, dressed as a woman, spinning purple wool with a spindle and assigning tasks to the girls, yet surpassing them all in femininity and indulgence. After seeing this, and outraged that so many men were subject to such a woman, and that people who carried iron weapons obeyed a wool spinner, he went to his companions, telling them what he had seen, and declaring that he could no longer obey a cinaedus who preferred to be a woman rather than a man. A conspiracy was formed, and war broke out against Sardanapalus, who, upon learning what had happened, reacted not like a man defending his kingdom, but like a woman terrified of death, looking for a place to escape. Defeated in battle, he withdrew to his palace and, having prepared a pile of fuel, set it on fire, throwing himself into it along with his riches, acting like a man for the first time.

However, Diodorus and Justin make some mistakes. Arbaces was the name of the Median king Cyaxares, mentioned in the section on the fall of Nineveh in the Mesopotamian Chronicles (some clay tablets written in ancient Akkadian with cuneiform signs) and the Behistun inscription. Most of the information about him comes from Herodotus, who, curiously, barely pays attention to Sardanapalus in the second of his Nine Books of History, and instead focuses on the lost riches:

Indeed, the thieves, wanting to steal the immense treasures of Sardanapalus, king of Nineveh, which were kept in underground vaults, began digging through the ground from the house in which they lived. Having taken the most precise dimensions and measurements, they extended the tunnel to the king's palace.

Wikimedia Commons)

Wikimedia Commons)

All this leads us to revisit the question of historicity, and it must be said that in the Assyrian King List, compiled by the Assyrians in their time, there is no mention of a monarch named Sardanapalus. The details of his life seem to partially coincide with those of Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria, and his brother Shamash-shum-ukin, to whom the former had ceded the crown of Babylon, though the latter was discontented because the Babylonian territories were much diminished compared to former times, a reason that led him to rebel in 652 B.C. with the support of Elamites, Egyptians, Syrians, Arabs, Suteans, Chaldeans, and, in general, all the enemies of the Assyrians.

Shamash-shum-ukin failed, and the defeat cost him his life; Babylon was besieged by Ashurbanipal for two years, finally falling in 648 B.C. The Assyrians sacked it and devastated it with their proverbial brutality, and Shamash-shum-ukin perished in the fire of his palace, though it is unclear whether this was voluntary or not. In ancient times, it was generally assumed to be voluntary, perhaps because the scribes wanted to avoid recording an execution ordered by his brother, which would have been considered impious since they were of the same blood. No one can overlook the similarity between the rebel's death and that of Sardanapalus.

It is possible that Sardanapalus was a syncretization of the two brothers. And what about the name? One theory suggests that it is a confusion with a satrap of Cilicia, but most scholars, based on the inscription known as the Çineköy inscription (a bilingual text in Luwian and Phoenician, dated to the 8th century B.C., engraved on a stone monument to the thunder god Tarhunza), lean towards an apheresis (a phonetic modification) of the word aššurû (Assyria), which gave rise to the term Syria and would explain the disappearance of the first vocal segment of Aššur-bani-apli, resulting in Sur-. In other words, Aššur-bani-apli would have been corrupted into Sar-dan-apalos.

Wikimedia Commons)

Wikimedia Commons)

Moreover, neither Ashurbanipal nor his brother Shamash-shum-ukin led lives as hedonistic as those attributed to Sardanapalus, and much less is there any evidence that they were homosexual or bisexual. Historically, they are portrayed as strong, ambitious, serious, and even cultured rulers (it is known that Ashurbanipal, under whose reign the Assyrian Empire reached its greatest extent, was a scholar who possessed a vast library and was well-versed in astronomy, mathematics, botany, zoology, etc.). As for the fall of Nineveh to a coalition of enemies led by the aforementioned Cyaxares, it took place in 612 B.C. after a series of civil wars for the throne.

At that time, Sin-shar-ishkun, a son that Ashurbanipal had with his wife Libbali-sarrat, was reigning after the murder of his brother and predecessor, Assur-etil-ilani, and after a few months when the usurping general Sin-shumu-lisir took power. The fate of the king is unknown, though it is assumed he died in battle defending the city. He was succeeded by Ashur-uballit II, who was probably his son but had to rule from Harran, as Nineveh had fallen to Babylon. Since the new capital was also conquered, Ashur-uballit II had to flee and, with the help of Pharaoh Necho II, returned to try to recover his kingdom; he failed and disappeared from history.

Returning to Sardanapalus, after his death on the pyre, he was supposedly buried in Anchiale, a city in Cilicia. In his work Deipnosophistae, the Greek rhetorician and grammarian Athenaeus of Naucratis recounts:

In the third book of his Walks, Amintas tells us that there was a colossal mound in Nineveh, which Cyrus had leveled to build a large terrace to better oversee the walls during the city's siege. This mound, it is said, was the mausoleum of Sardanapalus, king of Nineveh, on top of which a stone column had been erected, with inscriptions in Chaldean that Choerilos later translated into Greek verses [...] In Anchiale, a city built by Sardanapalus, Alexander set up his camp while fighting against the Persians. Not far from this place, he saw the tomb of Sardanapalus, where an image of the king was engraved, visibly depicted snapping his fingers. Below, these words were written in Assyrian characters: "Sardanapalus, son of Anakyndaraxes, built Anchiale and Tarsus in one day. Eat, drink, and enjoy! The rest matters little!" This, it seems, is the meaning of the finger snap.

That monument mentioned by the aforementioned Amintas (alias the Bematist, a writer from the 4th century B.C.) likely corresponds to the Achaemenid period and was built by a local satrap, as there is no record of any Assyrian king dying or being buried in Cilicia. The interesting part is the inscription because Diodorus of Sicily, always following Ctesias, reports the existence of a funeral prayer left by Sardanapalus:

...he himself made this epitaph in a barbarian language, which has since been rendered in two Greek verses: "I take treasures that I leave to the living; I invest everything in satisfying my senses."

It is unknown where exactly it was or in what language and script it was written, as it was said to be translated from Chaldean (Aramaic alphabet? Assyrian cuneiform?). Cicero, in his work Tusculan Disputations, traces knowledge of the epitaph back to the time of Aristotle:

We see in this the blindness of Sardanapalus, that opulent king of Assyria, who had the following inscription engraved on his tomb: "Deprived of my greatness by a fatal death, what Amor and Bacchus have provided me are the only goods I now dare to call my own; an heir has everything else." An inscription, Aristotle said, more fitting for an ox's pen than for a king's monument.

Reading these texts, it is easy to understand the terrible image the Greeks had of Sardanapalus: a degenerate monarch, captive to his excesses, combining tyranny with frivolity, feminization with weakness, fatally causing the collapse of his kingdom. The Macedonians associated these flaws with the Persians, and the Romans contrasted them with their own virtus, a perspective revived in the 20th century during Atatürk's era to explain the decline that led to the fall of the Ottoman Empire (the heir of the Sublime Porte was raised in a harem) and justify the republic. A bad reputation redeemed by art.

Sources:

- Dión Casio, Historia romana

- Diodoro Sículo, Biblioteca histórica

- Justino, Epítome de las “Historias filípicas” de Pompeyo Trogo

- Heródoto, Los nueve libros de la Historia

- Ateneo de Náucratis, Banquete de los eruditos

- Aristóteles, Ética a Nicómaco

- Cicerón, Disputaciones Tusculanas

- María Rosa Fátima, The legend of Sardanapalus: From Ancient Asssyria to European stages and screens

- Kostas Vlassopoulos, Greeks and barbarians

- Elena Cassin, ?Jean Bottéro, Jean Vercoutter, Los imperios del Antiguo Oriente. Del Paleolítico a la mitad del segundo milenio

- Wikipedia, Sardanápalo

or register to post a comment.