Özgür Politika)

Özgür Politika)

The documentary is titled Deserted Scream (Sahipsiz Çığlık), and is part of the Turkish Journalists Society's "Media for Democracy" project. Information and suggestions by Dr. Yaşar Kaplan, who has completed a doctoral thesis on the Church of the East Assyrians, and writer Vasfi Ak, a native Hakkari researcher, were heavily considered while producing the documentary.

Related: The Assyrian Genocide

The focus of the documentary is on the central churches of the Assyrians in Hakkari, St. Shallita in the Qudshanis district, St. Isho' Monastery (Dêra Reş) in the Şemdinli district, and some other churches along with selected religious buildings belonging to the Church of the East. From around 1685 until 1915, Qudshanis served as the patriarchal seat of that Church.

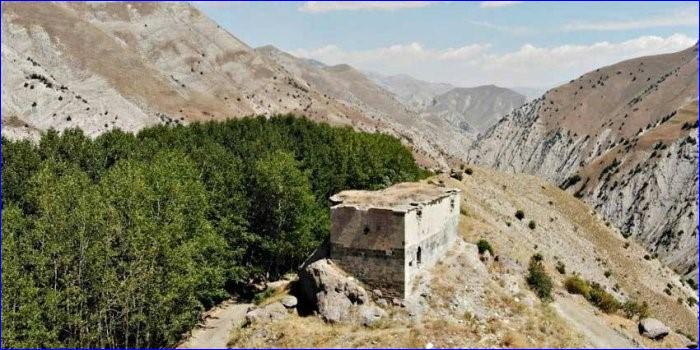

While documenting the remains of the church buildings, the historical background provided by experts about the Assyrians living in the regions has also been taken into consideration. The shooting of the documentary started about two months ago by the investigative journalist and author Emin Sari and was completed with a shooting at St. Shallita Monastery in the Kırıkdağ (Dêze) Valley.

Dr. Nicholas Al-Jeloo, an Assyrian experts on the geography of the Christian villages in the Hakkari and Bohtan regions, had the opportunity to meet and discuss the documentary project with the producers at the end of October. Dr. Al-Jeloo, born in Australia, is a descendant of Assyrians from Hakkari. In the past, he has travelled on several occasions to the Hakkari region and visited dozens of villages and churches in the district.

According to Emin Sari, "there are very important historical buildings within the geography of Hakkari," and that he wanted "to investigate these structures." As he didn't have the financial means to conduct this investigation on the historical buildings on his own, he prepared a project proposal on the subject and submitted it to the Turkish Journalists Society, which accepted the proposal. "We have been working for about two months for this and captured about 10 churches in Hakkari and its districts. We worked with a young team and academics who are doing research on the Nestorian [members of the Assyrian Church of the East] Assyrian. Now, we are coming to an end. We will present our documentary to the public in a month."

Noting that churches and other religious buildings in the Hakkari region are unattended, Sari argues that "an important part of churches and monasteries are about to be demolished. They are not preserved. I hope that through this documentary there will be interest in these structures. We want both to make the Assyrian people known and to motivate for work to be started to protect these churches. My hope is that the documentary we shot is appreciated by the public."

Related: Assyrians: Frequently Asked Questions

Journalist Vasfi Ak from Hakkari said, that the Dêze area, a district including 15 villages, contains a very old monastery building belonging to the Assyrians. The "building was built on a fountain. This indicates [source of] life," he added. It is "a very sacred place, but sadly it faces collapse. I hope it will be claimed and protected. We want the Ministry of Culture and the Directorate of Culture to protect such places," Ak concluded.

Yaşar Kaplan, a Hakkari University Research Assistant who conducted research on the Church of the East, said, "The Dêze area is one of the important centers of Assyrian Christians."

Standing in front of the St. Shallita Monastery, Kaplan commented that it "was a home for orphans. We do not know when it was built, but this is a place for the poor. Monks who devoted their lives to worship and prayer were staying here day and night. They did not get married. Until about 20-30 years ago, these places were intact. The villagers took care of them. But then the treasure hunters caused great damage. Sacred and historical places like this place are very important for our country. We expect such places to be restored and opened to tourism."

Related: Brief History of Assyrians

According to the project initiators, about 150 churches in Hakkari and its districts, which are important for the Assyrian/Syriac community, were destroyed, and the 30 remaining churches were destroyed by treasure hunters. There are also churches standing despite everything.

The documentary, shot in Kurdish, is expected to be released within two months.

I interviewed Dr. Nicholas Al-Jeloo about this project after his return from Hakkari. Dr. Al-Jeloo holds a PhD in Syriac Studies from the University of Sydney, an MA in World Religions (Eastern Christianity) from Leiden University and a BA in Semitic Languages from the University of Sydney. He is currently English Language Instructor at Kadir Has University in Istanbul, Turkey.

Abdulmesih BarAbraham (AB): Could you please introduce yourself briefly?

Dr. Nicholas Al-Jeloo (NA): In 2013 I completed my doctoral dissertation at the University of Sydney, focusing on the socio-cultural history and heritage of ethnic Assyrians in Urmia, Iran. My previous teaching experience was as a lecturer at the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne, specializing in Syriac Studies. Regarding my scholarly interests, I am a socio-cultural historian with expertise in indigenous Middle Eastern Minorities, Eastern Christianity, the history of the Middle East and Islamic World, as well as interfaith and intercultural relations. My specialty is in Syriac language, literature and epigraphy.

AB: What is it that drew you to visit the Hakkari region again. If I am correct, it has been your second visit this year. I remember seeing some of your postings from September.

NA: Yes. In September, I joined a small group that included two local Assyrians from Midyat in Tur-'Abdin, as well as a Swedish friend of the Assyrian community, who wanted to visit and document as many Assyrian-related sites as possible in Hakkari. This time, I had promised an Assyrian friend of mine, Norah Samano from London, England, that I would take her to where her ancestors were from in Hakkari, so that she could finally see and connect with those places. It also happened to be around the time that I found out about the documentary by Emin Sari about the Assyrian churches there.

AB: You have been in touch with people involved in producing a documentary that aims to film the remains of Assyrian "Nestorian" churches in the region. Did you have the opportunity to meet with the producers or were you able to preview and discuss the results of their recordings?

NA: Correct. I was able to contact the director prior to my visit and make it clear that producing a documentary about Assyrians, but without their voice or the opportunity to relate their own point of view, is unacceptable. As I was leaving for Hakkari the next day, and he lives in Van (which is only 3.5 hours away from there), he proposed to come meet us there and to conduct some additional shooting, in order to make the documentary more complete. I thought it would be also good for them to see that there is still interest in these churches from diaspora Assyrians, and that we still make attempts to visit them, despite the challenges, in order to clearly show that they have not been completely "deserted" by us. I additionally wanted them to know that there is clear potential for future visits by descendants of the people that lived there and worshipped in them, and that the intention is definitely there.

We left on Wednesday 28 October, and he met us early the next morning with a cameraman. We spent the entire day together as we attempted, unsuccessfully, to get permission to visit the Tal (Oğul) Valley, which is one of the places from where my friend can trace her ancestry. As a consolation, we opted to visit the ruins of St. Eugene (Mar Awgen) church, above the village of Ishteh d-Nahra (Darawa/Derav), where the stream of Walto meets the Upper Zab River. After filming my friend and I prayed the Lord's Prayer, I was then filmed explaining the interior architecture and layout of the church, and interviews were conducted with myself, my friend, as well as with her father in London (over video-call). While they insisted that I speak in the basic Turkish I have thus-far acquired, rather than English, my friend was interviewed in English and her father spoke to them in Turkish. Since they are based in Van, and I didn't have time to visit them there, I wasn't able to preview and discuss the results of their recordings. Emin did, however, promise to send me a copy to view before he releases it, in order to provide my opinion.

AB: How would you rate the documentary? It seems as a very good initiative, but what needs to be done to extend its focus?

NA: The initiative to produce the documentary is very noble and should have already been done long ago. The fact that it is happening now, though, is still something that must be appreciated, even though it will be in Kurdish. This would make the audience, or those who would potentially watch the documentary, very narrow. I made it clear to Emin that, at the bare minimum, it should be translated into English for the benefit of Assyrian viewers in the diaspora and have offered to help them edit such English subtitles. I am sure that they will provide subtitles in Turkish, and I will confirm that. It would be nice if more such documentaries are produced, both by Assyrians and non-Assyrians, in order to extend the perspectives offered on the historical and cultural heritage of the Hakkari region. For this, there needs to be more financial support and grants should be applied for from international and local institutions such as the EU and Turkish Cultural Ministry. This should also be done when it comes to restoring these edifices.

AB: According to reports, 150 churches and monasteries are located in the region. Does any systematic research exist on these holy places? How much of them have been located?

NA: According to my own research, some of which I published in the Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies (JAAS), there were around 250 churches, monasteries, chapels and shrines belonging to the Church of the East just within Hakkari province on the eve of the First World War. This figure does not include the small number of additional religious buildings which belonged to the Chaldean Catholic and Assyrian Presbyterian Churches. Of these, 102 have been located by myself and other scholars who have published studies on them, such as Prof. Mehmet Top from Van Yüzüncü Yıl University. Unfortunately, however, these are in Turkish and are not accessible to those who can't read the language. I have personally been able to visit and document the sites of about 70 religious sites in Hakkari alone and, while I don't have data for 150 of them, I can report that out of the roughly 250 in my list, 67 are intact or in various stages of ruin, while 35 have been completely destroyed -- some of which may require archaeological excavation.

Outside of the current boundaries of Hakkari province, there are another 36 churches in Van province (Central, Özalp, Muradiye, Saray, Başkale and Gürpınar districts), at least 12 in Şırnak province (Uludere and Beytüşşebap districts, some of which have been documented by Dr. Zekai Erdal from Mardin Artuklu University) and 2 in Kars province, not to mention those in the Pervari district of Siirt province, which belonged to the Church of the East and should be investigated. I have been able to visit some of these and document them, but much more needs to be done.

AB: Do any initiatives exist to place or register all the churches and monasteries under the umbrella of a religious foundation similar to the foundations that exist for other Assyrian churches in Turkey?

NA: In 2014, while he was Metropolitan of Iraq and Russia, the current catholicos-patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East, Mar Gewargis III Sliwa, paid a visit to Hakkari and met with various local dignitaries. Among them were the provincial governor, as well as Assyrian lawyer Erol Dora who, at that time, was serving as a parliamentarian in Ankara. I was lucky to be there on the first day of his visit and recommend some sites for him to inspect. Back then, there was the suggestion to set up a religious foundation for the Assyrian Church of the East, which currently holds no legal status in Turkey. Unfortunately, this was not seen through and there have been no subsequent visits by any prelates from the Church, leaving local stakeholders cynical and lacking hope. Neither does it seem that this important issue has been discussed in the Church Synod meetings since, which is quite unfortunate.

There are, however, people and institutions in Turkey who have -- on numerous occasions -- offered to help the Assyrian Church of the East in this regard. Among them are Assyrian individuals who identify themselves as adherents of the Church, despite its official absence, and even those who belong to other Churches but wish to help in founding a viable religious foundation or association for it. There have even been offers from the two Metropolitans of the Syriac Orthodox Church in Mardin and Tur-'Abdin, as prelates of sister Churches, to act as guarantors for properties belonging to the Assyrian Church of the East, as well as the local Chaldean Catholic Church, which has offered to register the abandoned properties under its own foundation. Unfortunately, it seems that none of these avenues have seriously been explored.

The main issue, though, remains one of ownership. Most of the religious sites previously belonging to the Church of the East are now registered as private or government properties, since the Church itself has not been present in Turkey as an official active religious institution since its founding as a republic in 1923. This is the main stumbling block which needs to be overcome if the Church actually wants to own the structures and their adjacent properties, rather than just having them restored. The records for the parcels on which these buildings are located can all be found at the local cadastral (tapu) registry, as well as their histories of ownership. That's easy enough, but it requires research and a clear move from either the Assyrian Church of the East, or people/institutions that they delegate to deal with the issue. Otherwise, the religious buildings can be restored without becoming the property of the Assyrian Church of the East and remain in government or private hands, just in order for them to be protected, preserved and open for tourism.

AB: What can Assyrian organizations in the diaspora do to help document the remains of these churches and monasteries in the Hakkari region?

NA: Back in 2004, I presented the same lecture at the Assyrian American National Convention, the Symposium of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies and the annual meeting of the Middle East Studies Association of North America regarding the state of Assyrian cultural heritage sites across the homeland. Back then, I proposed the establishment of an Assyrian Cultural Heritage Foundation, which would operate internationally in order to document, as well as safeguard the conservation, preservation and proper restoration of endangered sites relating to our people's history. Unfortunately, that call fell upon deaf ears and nothing eventuated from it. That was 16 years ago, when I was in the last year of my undergraduate studies.

While most Assyrian diaspora organizations are focused on their own local communities or helping those in need, and that is totally understandable, there really should be a minor focus on our nation's heritage -- and that includes important historic buildings and structures that constitute our tangible cultural heritage which are, for all intents and purposes, abandoned and not looked after by any government institutions. This doesn't necessarily have to be in Turkey and doesn't need to solely entail expensive and complex endeavors such as restorations or renovations. For instance, it could be as simple as funds allocated for assisting specialists in the documentation of these sites, maybe even the publication of several reports, a website, or even a series of documentaries. It would even be great if a specialized scholarship could be set aside for those wishing to achieve the credentials needed for this kind of work. Let us not forget that, as a stateless ethnic group, we must either take action ourselves or lobby the countries which now govern the various segments of our homeland for them to do so. The main issue is that the Assyrian public is not very well informed about their heritage, both tangible and intangible and, as the diaspora grows and communities in the homeland shrink, this is going to become more and more important (and difficult) to achieve. I hope that we can start laying the foundations for this as soon as possible!

or register to post a comment.