Dilan Karaman)

Dilan Karaman)

Kafro, which sits 14 miles (22.5 kilometers) outside the town of Midyat in Mardin Province, was historically an Assyrian village, inhabited by followers of the Syriac Orthodox Church. Many Assyrian Christians regard the surrounding Tur Abdin region, a hilly area that forms parts of Turkey's Mardin and Sirnak provinces, as the epicenter of their cultural heritage.

Unlike other similar villages, however, Kafro has a turbulent recent history. In 1995 it was forcibly evacuated by the Turkish military as a security measure during the conflict with the Kurdish separatist PKK, which has a strong presence in the region. Caught in a war zone, suspected by the Turkish army of aiding the PKK, and facing financial difficulties as a result of the conflict, many Assyrians left their traditional homeland. In Tur Abdin, where the Assyrian population was most dense, their numbers have declined to around 3,000.

The flow of departures was also true for Kafro, as many inhabitants left for destinations in Europe. They have since set up the Kafro Village Rehabilitation Association Fund, based in Switzerland, to collect money to renovate their hometown. Around 15 families contributed to this joint pool, and they have used the funds to rebuild their houses once they have decided to return to Kafro (with not all of them returning at the same time). Nail Demir's father, Yahko, was the first to came back and he built several houses at the entrance of the village for families who put money in the pool and wanted to return. As a result of this joint effort, a dozen families have made the journey back so far, starting in the mid-2000s.

Keeping a Low Profile

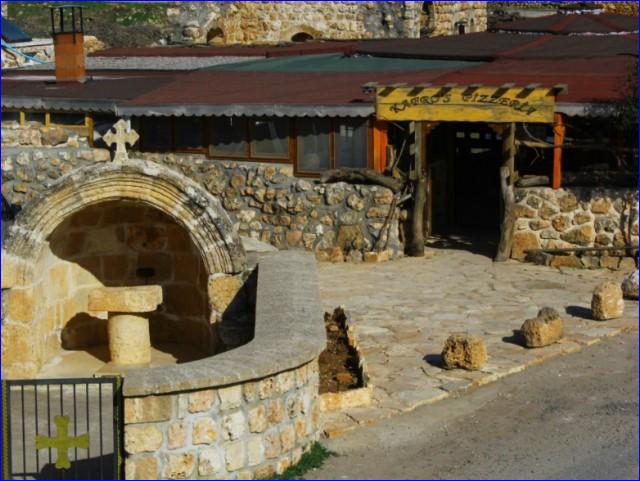

Demir, now 54, returned to Kafro from Germany in 2008, opening his pizza restaurant two years later. "We came here with my wife and two kids," he said. "After our children finished high school, they went back to Europe and we're back here making pizza."

Now, returning Assyrians are trying to reclaim their heritage, promising to "Europeanize" -- to economically develop -- the property they reclaim. Demir said he came back "to apply what I learned in Europe, to elevate my hometown."

Dilan Karaman)

Dilan Karaman)

Demir was wary of speaking to a journalist, and other residents of Kafro refused to speak at all, including the village mayor. Kafro's revival has attracted media attention, and there's a sign across the road from the pizzeria saying "don't photograph people without their permission." Residents remain afraid to say anything that might be construed as anti-government or manipulated to sound that way, and that they then might be punished in some way as "traitors."

In nearby Midyat, Yakup Gabriel owns a factory that produces some of the region's famous Assyrian wine. The 58-year-old Gabriel left Midyat in 1975 for Switzerland, returning with his family in 2002. One of the wines he sells is called Monastery.

"House wine used to be sold under the table, which gave Assyrian wine a bad name," he said. "We built this place to make pure and delicious wine, to better represent our culture."

Assyrians began returning to the region during attempts at political negotiations between the Turkish government and the PKK. The most recent of these collapsed in 2015, as the civil war in neighboring Syria contributed to the breakdown of a ceasefire agreement.

Related: The Case of the St. Gabriel Assyrian Monastery in Midyat, Turkey

"I came back when my children were still young so that they wouldn't grow up as strangers to their homeland," said Gabriel, who was one of the first to return to Midyat.

A History of Violence

Conflict goes back much further than the 1990s, however. Under the Ottoman Empire, the region was populated by a variety of ethnic and religious groups, including Assyrians, Armenians, Yazidis, and Kurds.

During the violence of 1915, which led to the deportation and death of hundreds of thousands of Armenians, much of the non-Muslim population was killed or expelled. Those who remained were subject to the newly formed Turkish Republic's demographic policies, which attempted to permanently alter the make-up of the region by resettling Kurds -- and then, when they later fell out with the government, Arabs and Turkmen -- around the Assyrian villages.

Some Assyrian land and property were seized back then and held in trust by the government, which means returning Assyrians still today often have to apply via the courts to reclaim or buy it back.

Not everybody left, though. A 53-year-old woman who didn't want to give her name, said that her parents resisted the pressure to leave when she was a child.

"I didn't understand then but I think I see it now. The idea of relocating a tree is scary when it's already deeply rooted in its own soil," she said, speaking by phone due to restrictions on movement imposed during the coronavirus pandemic. She has three grown-up children, who she says live more comfortably with their own cultural traditions than she used to.

A 44-year-old businessman in Midyat, who also didn't want to give his name, likewise feels that Turkey's government now allows Assyrians to live more freely. He is glad to see others returning from abroad.

"Compared to what it used to be like, the political climate these days is better suited for Assyrians to do constructive things in their own lands," he said.

A Declining Assyrian Population

Not everybody agrees. Numan Ogur, 54, is co-chair of the Mesopotamia People's Assembly. His organization, which draws on some of the ideas of the PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan, would like to see a "democratic confederacy" established in Mesopotamia, the historic region between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates that covers parts of modern Turkey, Syria, and Iraq. This would be a society based on socialist principles that does not tie ethnic and religious groups to a particular nation-state.

"There's no opportunities for access to culture," said Ogur, who lives in Germany. He pointed out that only around 40,000 Assyrians remain in Turkey, a fraction of the global diaspora. Assyrians have faced discriminatory religious policies since the foundation of modern Turkey, Ogur said, adding that they are also frequently accused of being American spies, or of secretly aiding the PKK.

According to a study by the academic Nese Ozgen, the decline in the region's Assyrian population had several causes. The first came in the 1940s, as a result of demographic policies to encourage the Islamification of the region. The second was after 1955, when many rural Turks migrated to the cities, and the third came in the 1970s as people sought better education and economic prospects elsewhere. Finally, from the 1980s onward, came the government's conflict with the PKK.

Ogur was given a traditional, monastery-based education as a child during the 1980s. This starts at the age of five, and covers everything from Assyrian language and culture to mathematics and music. This curriculum is officially banned under Turkey's education policies, but state authorities reportedly turn a blind eye in many instances.

"When I was raised in the monastery, we were under extreme pressure. That pressure is still on," said Ogur. Neither the Mardin governor's office, nor the district offices, would answer a request for comment on returning Assyrians and integration policies.

Assyrians living in Mardin Province have a range of political inclinations. While Gabriel, the winery owner, was once a member of the pro-Kurdish, multiculturalist People's Democratic Party (HDP), the Assyrian archpriest of Mardin is aligned with Turkey's governing Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Yet even Ogur thinks that many Assyrians would return to their historic homeland if peace could be guaranteed, adding, "The Assyrians are the oldest proprietors of the land they live on."

or register to post a comment.