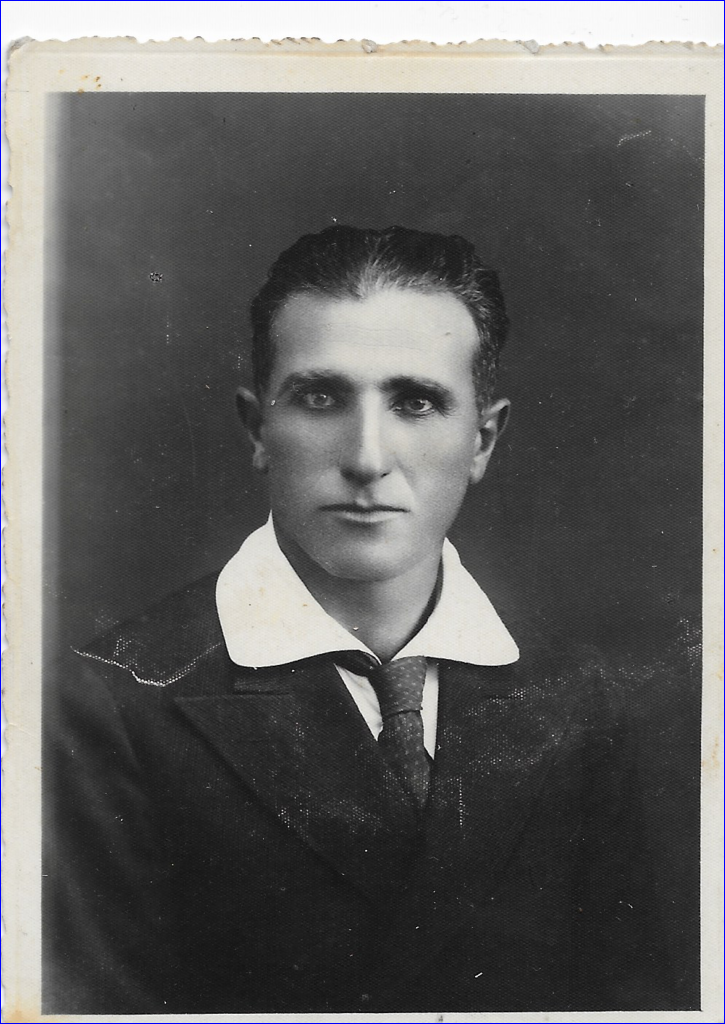

I first came to know him as a child at the house of his daughter, my mother's maternal aunt, Nora, in Iran's capital, Tehran. His midsize photo hung on the dining room wall. A black and white portrait of an unsmiling middle-aged man. I cannot say I liked the photo. His glass-eyed emotionless gaze scared me a little bit. He seemed to have nothing in common with that household and my family.

We would go to Nora's house quite often. Nora and her Armenian husband Jean lived with their two daughters, Antoinette and Antonella. Nora's sister, Nelly, lived with them too. I loved going there. In my childhood eye, Nora's place was like a wonderland. It was full of colors: home- baked cakes with layers of blue, yellow and red in them, kaleidoscope quilts knitted by Nelly, and various lovebirds chirping in separate cages. But the most fascinating part was Nelly's special collections -- the ones children dared not to touch: the collection of matchboxes, the collection of stamps, the collection of card decks, the collection of small liquor bottles, the collection of The Adventures of Tintin comic series.

To add to the vivacity of Nora's house, there were usually guests around. Everybody would sit around the dining table, drink Turkish coffee, smoke, play cards and talk nonstop. That dining table was my childhood United Nations. Everyone spoken multiple languages simultaneously. My grandmother, Jenny, and her sisters would speak in Assyrian, constantly calling each other khati, "my sister": "Jenny khati," "Nelly khati," "Nora khati." Then they would shift to Azeri to communicate with their Azeri friends. Jean would speak in Armenian with some guests. If my grandfather, Alec, was around, he would also throw some Russian. Eventually, on some occasions, if there were some non-Azeri, non-Assyrian non-Armenian Persians there, so they would also speak in Persian. What a surprise to find Persian-speaking Persians in Iran!

In this vibrant scene, the black and white photo of that serious communist was a misfit. At least to me it was. My childhood curiosity only drove me as far as learning that he was my grandmother's father. He was called "Rabi Yushia," meaning Yushia the Teacher, or the Master, and his family immensely respected him. I did not need to know more. He was boring to me. So I ignored him.

Later, unintentionally, I gathered a few more scattered pieces of information about him. He studied in Russia. He became a communist. He was politically active in his hometown Urmia, the capital of Iran's West Azerbaijan province. He was executed there for his communist activities in the mid-1940s. That did not interest me either. I continued to find him boring. I continued to ignore him.

It was years later in 2016, thousands of miles away from Iran that I was reminded that Rabi Yushia's life was nothing but boring. I was at my mother's home in Glendale, California. For days my mother was saying that she worried that all the childhood photos of my sister and me had been lost during our migration from Iran to the United States. We decided to look for them. I knew she kept a big box of photos under the bed. I pulled it and together we went through a stack of colored photos. But soon we forgot our mission. We were instead drawn to the black and white photos. There were hundreds of them. I had seen them before, but they never really interested me. This time however, maybe hit by nostalgia, I was hooked. There he was again. Rabi Yushia. That same photo. But now there were more photos of him. Rabi Yushia as a teenager. Rabi Yushia as a father. Rabi Yushia sitting with a friend. Rabi Yushia posing for a family photo.

I reshuffled my memories and tried to remember what I've heard about him. It consisted of snippets: Rabi Yushia goes on the run. He gets arrested. He is hung. His whole family is shattered.

I was fixated on two photos, both taken in early 1940s. In one, Rabi Yushia and his wife are having a picnic with friends and family in a garden Urmia. Rabi Yushia is wearing a flat cap. He is poking his head out, looking at the camera without a smile. He is playing backgammon, a very common game among the Assyrians. They are drinking. His wife Daya (Diana) is sitting next to him. She's wearing a bright-colored dress and Mary Jane shoes. With a slight smile, she is raising her glass, giving a toast to the camera. From the shade of the drink, I assume it is red wine. Urmia was known for its vineyards. They all look happy and at ease.

The other image is not in as good condition. It is actually a double exposure. Again, it was taken in Urmia, in the middle of a field. My grandmother is holding a banjo in her hand. She was apparently a good banjo player, though I never saw her play. Her hair is braided on both sides. She is running toward the camera. Rabi Yushia is standing in the middle. He is taller than the rest. But this time, it looks like he is smiling.

Looking at these photos I think, so there was a time that things were not bad. There was a time that this family, the Bet-Daniel family was not suffering. There was a time that they were living happily in their beloved Urmia.

Located in the northwest of Iran, Urmia is more than 6,000 years old. When Reza Pahlavi became the crown prince of Persia in 1925, he renamed the city Rezaiyeh. The name Urmia was restored after the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran. It is well-known for its gardens, vineyards and good wine, and some Iranians like to call it the Paris of Iran.

There is a debate on why the city is called Urmia. One version claims that the word has a Syriac origin meaning "city of water," while another one asserts that the name has an Indo-Iranian origin which means "undulating" or "wavy." If you ask most Assyrians, they will pick the first version, explaining that in Syriac "Ura" means city and "Mia" means water. Whichever explanation we prefer, what is obvious is that both names refer to a body of water. Specifically, Lake Urmia.

Being close to today's Turkey, Iraq, Armenia and Azerbaijan, Urmia has always been a hotbed of different religious and ethnic minorities, mainly Kurds, Armenians and Assyrians.

Assyrians have populated this region since the 9th century B.C. when parts of current Iran belonged to the Assyrian Empire. After the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 609 B.C., Assyrians who lived in the region that is now part of Iran, including Urmia, remained there. In 33 A.D., tradition says, they converted to Christianity.

I have been to Urmia a few times. I've even swam in Lake Urmia as a kid. It was summertime in the early 1990s. We were visiting my mother's aunt, Jenny's older sister, Zarina. She was the only sister still living in Urmia. I remember my sister and I playing in their garden, running through the rows of trees. Then we went to Lake Urmia to swim. We found somewhere isolated so that women could swim too because in the Islamic Republic, women are not allowed to be bareheaded in the public, let alone wear only a swimsuit. The water was warm. It was so salty that you could float weightless on the water. My memory is foggy but I clearly remember Auntie Zarina swimming in a tight swimming cap. Her long breaststrokes gently carried her frail body forward as she strained to keep her head above the water. I was wildly splashing my feet and unintentionally spraying salty water into Auntie Zarina's mouth and eyes. She asked me a few times to stop splashing the water.

That is my image of Urmia. A scene fixed in my mind like a miniature. Looking at those photos in 2016, it suddenly struck me: The Urmia I visited is the same Urmia where my grandmother, my Mama Jenny, was born and raised. It was the same Urmia where Rabi Yushia was hung in its main square. How did I miss this link? While we were visiting Urmia, did we ever pass by that square? Did we walk by my grandmother's childhood home? Who knows.

I had never asked anyone anything about Rabi Yushia. To me, Rabi Yushia was a stranger. My careless mind did not even connect Rabi Yushia to my family. To his family. To me, he was a character living in a capsule by himself. It had not occurred to me that he was a son, a husband, a father. My Mama Jenny's father.

I had not even asked the most basic questions about him. I had heard several times that Rabi Yushia's father was an Russian Orthodox priest. Then why and how on earth did his son go to the other extreme and become a communist? How did Rabi Yushia's father receive his only son's decision? Did he approve or was there a fight between the father and son?

There were other bits and pieces of information that must have provoked me to ask questions on that day in Glendale: After Rabi Yushia's execution my grandmother went into hiding and eventually ran away to Tehran. How, when, and why did she hide? Was the government after her? Was she also a communist? What about her family? Were they also communists? I vaguely remember hearing that Zarina used ride a horse into the mountains to take aid to some communists hiding there. I remember hearing that at some point Nelly was arrested. Did these events really happen? Or is my memory playing tricks with me, making up these stories?

Not knowing about my family history was only a part of the issue. The bigger issue was that I had never seen the Bet-Daniel family in the context of historical events of Iran and the region. In my mind, the Bet-Daniel family lived in a bubble, disconnected with the rest of the world. In this bubble Rabi Yushia's father was the only Orthodox priest and Rabi Yushia the only communist.

I had not thought of the Bet-Daniel family as part of any larger community: the Assyrian minority in Iran, the Christian minorities in Iran, Iran's Azerbaijan, Iran as a whole, or even the Middle East. I somehow missed how they were tied to the historical events that shaped the region: World War I, the October Revolution, World War II, the Cold War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. They were also affected by the historical events of Iran: the advance of communism in Iran during the early 1940s, the 1953 Iranian coup d'état and the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

That day in 2016 in California I sat there with questions buzzing in my head. I asked my mother some questions about Rabi Yushia. She didn't know much. She said that nobody in her family really liked to talk about what happened to him. I asked who might be able to answer even the most basic questions. She said most of the people who knew were either dead or too old.

She was right. Rabi Yushia's children are all dead except for Nora. She is in her late 80s, living in Hamilton, Canada. I called her and asked about Rabi Yushia. She did not remember much. I asked where Rabi Yushia had studied. Either Tbilisi or Baku, in what was then the Russian Empire/the Soviet Union. She couldn't remember which. I asked about his studies. At first, he studied theology, she said, then he transferred to law.

But these shaky facts only elicited more questions: Where did he study in the end? In which university? Is there information on Yushia's time in Russia sitting somewhere in an archive? Where is that archive? In Tbilisi or Baku? Or maybe Moscow, or St. Petersburg?

After my conversation with Nora, I reached back again into my memories of Nora's home in Tehran where I first saw Rabi Yushia's photo. As I pictured the dining room, I found something ironic, something I had never thought about before. Rabi Yushia's photo with its humble frame was hanging all alone on a wide white wall. Then on the wall to the left was a big copy of Salvador Dali's Crucifixion. On the other side of the dining room, a reproduction of Michelangelo's Pieta stood on top of the television. There was a long console that would fill with dozens of postcards every Easter and Christmas. And every Christmas, Nora's famous tree would appear. Every year the family would buy such an exaggeratedly big tree. Sometimes in order to fit the tree in the room, they had to bend the tip of it against the ceiling. There were crosses everywhere: hanging from the door knob and worn by Nora and her family. No wonder I ignored Rabi Yushia's photo as a kid. How could I not among all those Christian symbols?

Could Rabi Yushia who turned his back on his father and Christianity imagine that one day his photo would overlook a dining table where his family would celebrate Easter and eat paska, Easter bread? What had happened to Rabi Yushia's communist ideals? In the end, were the Bet- Daniels communists or not?

Now that I think about it, Mama Jenny definitely believed in some communist ideals -- equality, sharing, camaraderie -- but she was also a Christian. At least she believed in the Virgin Mary. That I know for a fact. So how is this possible? How can you be both?

I needed to learn more about the Bet-Daniel family. I had to understand how a family that once lived happily together in Urmia was shattered and scattered across Iran in 1946. And I saw that I could not make sense of any of this without plunging into the history of Iran and the region.

I had to understand how Assyrian life was in Urmia. I needed first of all to go back to the late 1800s, when the seeds of misfortune were planted in the Bet-Daniel Family -- when Rabi Yushia's father converted to Russian Orthodoxy, when the American Presbyterian Mission and the Russian Orthodox Mission were working as rivals in Urmia, trying to convert Assyrians from the Assyrian Church of the East and Chaldean Catholic Church. When Americans and Russians competed for Assyrian souls in the Azeri corner of Iran.

or register to post a comment.