In Trapezounta, the centre of Pontic Hellenism, no Greeks were targeted at that time. Instead between one and two thousand Armenians are believed to have been killed, out of a total community of 9,000. In later phases of the genocide, Armenians of Trapezounta would be taken out into the sea in boats, slaughtered, and thrown into the water. A very brave Pontic Greek woman, a latter day Antigone, rescued many of the corpses washed up into the shore and at great peril, buried them near a Catholic church along the seafront.

Related: The Assyrian Genocide

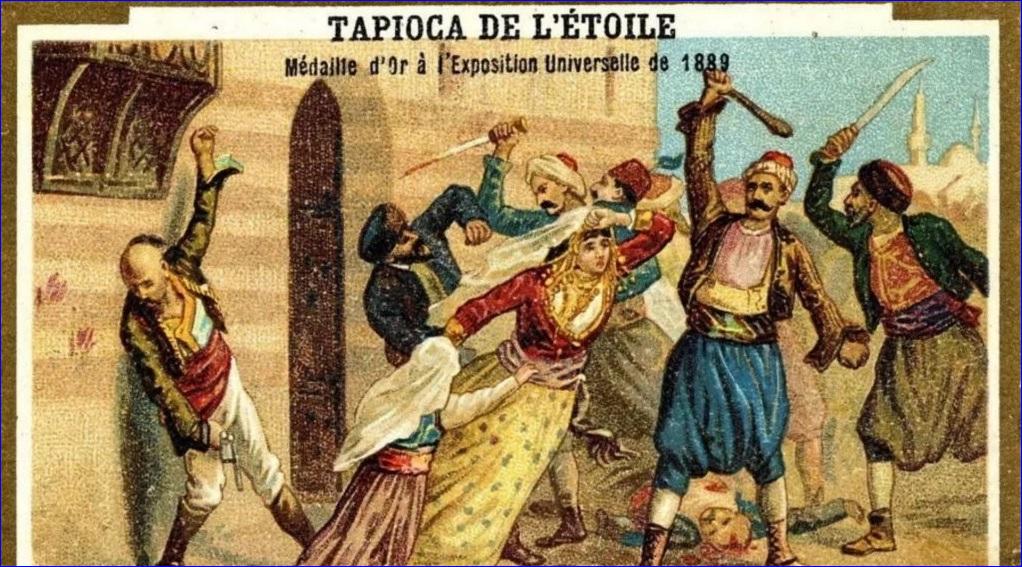

Yet during the Hamidian massacres, British consul Henry Longworth, who was an eye witness to the massacre, wrote that after the Turks shot down every Armenian they encountered during a street rampage, joined by "Greeks and Persians," the mob systematically looted Armenian "houses, shops and storerooms throughout the town, killing anyone who resisted." At that time, it is alleged that certain Pontic Greeks were actively complicit in acts of genocide, as the term is understood in its international legal sense.

British consul Longworth went on to write: "Greeks possibly in fear, refused in the majority cases to shelter the hunted down people in their shops and houses, schools and churches." They closed their homes to the most vulnerable of their neighbours at a time when they needed assistance the most. In so doing they most likely contributed to the horrific deaths of the hapless Armenians, by the marauding Turkish bands. Of course, two decades later, when it was the Greeks of Trapezounta who began to fall victim to the genocidal policies of the Neo-Turks, there exist countless stories of Greeks hiding the children of their Armenian neighbours, or handing them over for protection to the occupying Russian army. These are two ostensibly contradictory modes of conduct that are almost never analysed and are generally effaced from Greek narrative of the genocide, which in part, although this is changing, tends to ignore the experiences of other victim groups, save where these highlight the enormity of the crime visited against the Greeks of Asia Minor.

We don't know whether other examples of Greeks or indeed Armenians aiding and abetting Turks during the genocide exist, and if they do, why they took place. No doubt, if they exist, they could be understood through the prism of self-preservation and self-interest. And it is important to point out that the account of the Greek complicity in the Hamidian massacre in Trapezounta is one infinitesimally small event that is almost completely overshadowed by decades of common suffering and mutual assistance. In Greece, Armenian refugees found a home and sanctuary. Assyrians fleeing their homelands in the face of persecution and religious intolerance that has continued unabated since the Genocide, still do, in the present day.

Yet the single fact that some Greeks felt it expedient to persecute their Armenian neighbours deserves our attention. This is because some genocide activists employ the genocide in a manner that can only be termed almost pornographic. They take perverse delight in providing detailed, blow by blow accounts of the harrowing physical, sexual and emotional abuse meted out against the Greeks and other Christians. Their eyes shine with glee and artfully placed tears trickle down their cheeks as they quote statistic after statistic to highlight just how many people were killed, while they try to also quantify the magnitude of the economic and cultural loss. In their accounts, our people are (quite rightly) victims. Their stoicism in suffering grants them a nobility that is juxtaposed against the barbarity of the people who took part in this heinous crime against humanity. As such, partakers in the narrative are invited to make assumptions about the characteristics of a whole race. Accordingly, entire races are surmised to harbour genocide-perpetrating propensities within in them.

The knowledge that some Pontic Greeks, perennially cast as victims, took part in the Hamidian massacres against the Armenians, seems to come in stark contrast to the well-worn narrative of racial stereotype. Given that as a people we are so generous, so valiant, so democratic and so humane, how is it possible that even the slightest proportion of us could have stooped to the level of the perpetrator who will forever bear the brunt of our ire? It is either impossible or a blatant lie. The argument is that as a 'superior' people, we are above such acts of bestial brutality that are the preserve of 'lesser' races. This is why racial stereotyping of this manner is so dangerous, as it carries the seeds of future intolerance within it.

Rather than indulge in racial profiling or attempts to explain the event away as a negligible aberration that is not endemic to our people, what this specific Pontic Greek act of participation in the massacre suggests, is that the tragedy of genocide is that this failure to maintain humanity is something that can afflict all of us, regardless of race or religion. All of us are capable of such acts, given the right amount of coercion, suggestion, or encouragement.

Understanding the fact that the seeds of magnanimity and compassion but also of depravity lie within all of us, and that all of us have moral choices to make that are not always without cost when called upon to maintain or transgress the standards of humanity, will assist us in gaining a true insight into humankind's ability to turn on one another. It will help us to comprehend why the muslim inhabitants of Mosul were able to collaborate with ISIS and commit heinous acts upon the Christians of the city in our own time. It will facilitate understanding of how incited by hate speech in the media, Hutus were able to attack Tutsis, people of the same nationality and murder them in drives in Rwanda. It will help us to place into context, the manner in which Greek was able to denounce and slaughter Greek, during the bloody Civil War. It will also go a long way in explaining why a disaffected socially privileged white person came to nurse grievances that came to be symbolised by the names of obscure historical figures which he scrawled upon his murder weapons as he live-streamed the slaughter of innocent muslims in the mosques of Christchurch. No one, and certainly no race is immune from crimes of violence and intolerance.

All these events, demonstrate how the societies in which we live and pride ourselves occupy a precarious existence, perched upon the precipice of order in danger of decent into anarchy, safety, descending into bloodshed. The Turkish Prime Minister's latest pronouncement, that the deportation of the Armenians was a perfectly appropriate act, signifies just why the maintenance of a civil and democratic society, in which human life and its ability to thrive and express itself in safety and within a climate of respect is so vitally important.

The world has failed the victims of the Christian genocide. A hundred years on, most countries, including our own, in the interests of political expediency, choose not to recognise these terrible events as genocide. In so doing, they have arguably permitted would-be perpetrators to understand that they can commit their crimes with impunity. The slaughter of the Christians of the Middle East by ISIS, many in the very deserts of Syria and Iraq where their ancestors were massacred by the Ottomans before them, can be deemed to be a logical outcome of this cynical behaviour. A society that witnesses suffering and yet cannot place it in its historical context in order to condemn it, is a society in peril.

Yes, some Pontic Greek opportunists seem to have aided and abetted the Neo-Turks in their disgusting crimes in Trapezounta, just as some modern Greek opportunists aided and abetted the Nazis in the commission of the Holocaust in Salonica. We remember them with the scorn they deserve. We do not trivialise or seek to hide their crimes. Those crimes do not in any way stigmatise us as a people. Nor do they in any way, defile the memories of the innocent victims of the genocide. Instead, in teaching us that given the right amount of goading, no one is immune from barbarity, they stiffen us in our resolve to call out intolerance where we see it and demand from our leaders that they take the necessary steps to preserve our democratic way of life. A good place to start is by officially recognising the genocide of the Christian peoples of the Ottoman Empire, creating the moral opprobrium that will prevent similar massacres ever being repeated in the same region again.

or register to post a comment.