Mar Chalita is the Syriac name of Saint Artemius, a fourth-century Roman general from Antioch. The name Chalita means "the governor," from the Syriac verb "chlat" (to rule, to govern). A destroyer of idols and hated by the people of Alexandria, who denounced him, Mar Chalita was martyred under Emperor Julian in Antioch around 362--3. Several churches and monasteries in Lebanon are dedicated to this saint, the most important being those of Qbayét and Ghosta.

The founding of the monastery

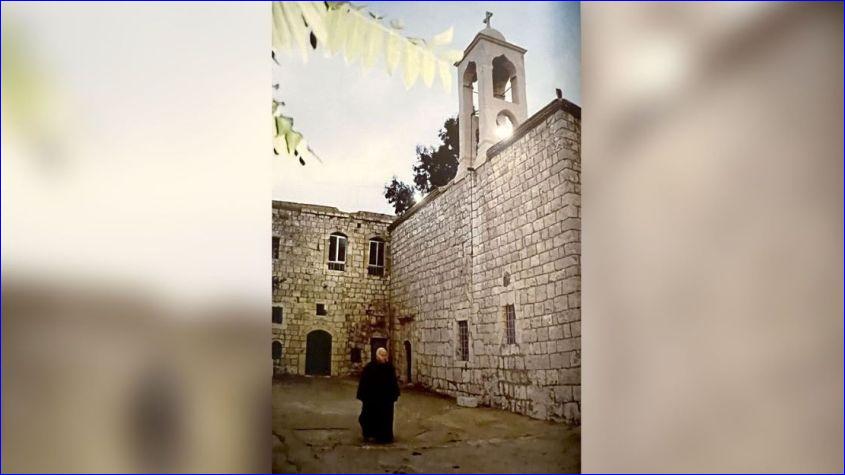

The monastery of Mar Chalita of Ghosta is also known as Moqbes. According to the Maronite bishop Theodore of Ain-Qoura (Aqoura), it was founded in 1192 by a Frankish knight, nicknamed Bacchus by the Lebanese. As recounted in a fourteenth century manuscript written by Maronite Bishop Theodoros and preserved in Bkerké, Bacchus, acting as a representative of King Philip II Augustus of France (1180--1223), endowed the church with several ornaments, including a gold cross.

Like most of Keserwan, which included today's Metn district, the Mar Chalita Monastery was razed to the ground during the Mamluk genocide of 1305. Its decimated population fled to the northern regions between Tannourine and Bcharré. It was only after the Mamluks withdrew before the advancing Ottomans in 1516 that Christians began to return and rebuild their villages after two centuries of desolation. As elsewhere in Keserwan, the Chouf, and Jezzine, people had to dig deep into the ground to find the foundations of their old villages and churches. This long process of rebuilding and then modernizing lasted four centuries, until the First World War, reaching its peak under the rule of Fakhreddin II the Great (1592--1635).

The reconstruction of the monastery

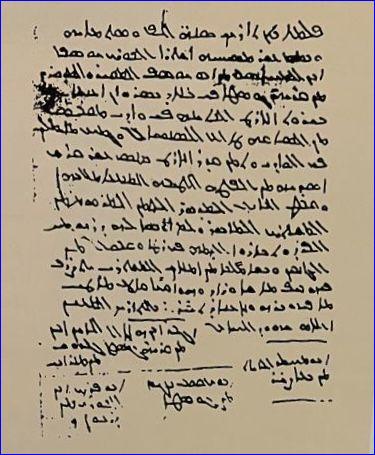

It was at this time, in 1615, that a Garshuné purchase deed was drawn up, by one Joseph, son of Mohasseb, of the site in Ghosta where the ruins of the medieval monastery of Mar Chalita had been discovered. The monastery was rebuilt in 1628 by the priest John Mohasseb, as stated in the Garshuné epigraph carved over the church entrance. In 1670, Patriarch George of Bsebeel died there and was buried in the monastery. His successor, Patriarch Estéphanos Douaihy, also resided there briefly.

The church was renovated in 1672 during restoration work undertaken by the priest Sarguis. This is recorded in one of the many inscriptions now inserted in the nave of the church. It reads in Garshuné script: "In the name of God, in the year 1672 of Our Lord, this holy sanctuary was renovated, in the time of our lord Patriarch Estéphanos the Antiochian..."

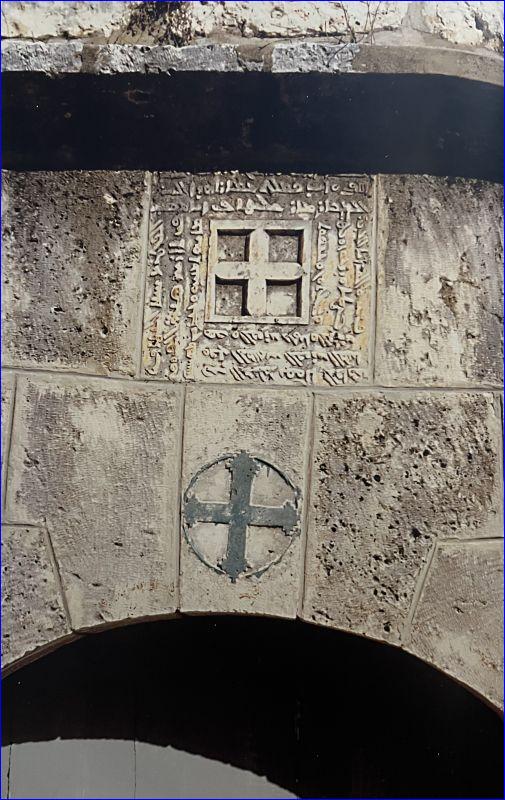

The epigraph of 1628

The main epigraph, carved around a cross at the church entrance, dates from 1628. It is the first Maronite inscription to appear after three centuries of silence since the epigraph of Our Lady of Ilige (1276--77).

The centuries of Mamluk rule created a cultural void, bringing the construction of churches, schools, and monasteries to a standstill. Syriac inscriptions stopped in 1277 and did not reappear until after 1628. This long period of desolation left deep marks on Lebanon's population and its Church.

We see significant changes. Before the Mamluks, all stone inscriptions were in Syriac, whereas in the seventeenth century they also used Arabic written in Garshuné. Monumental script, i.e. square Estrangelo script, gave way to the cursive Serto script. Intaglio writing disappeared, replaced by the technique of raised relief letters favored by the Muslim tradition of the Arabs and Turks.

The epitaph of 1670

Among the structures of the Mar Chalita Monastery stands a rock left in its raw natural state. It has a medallion engraved in Syriac inscription of exceptionally fine calligraphy. The contrast with the raw stone is striking. The language used is Syriac, not Garshuné as in the other church epigraphs. This is the epitaph dedicated to Patriarch George of Bsebeel, who died at Mar Chalita in 1670.

This renowned patriarch was mentioned in 1918 by French consul René Ristelhueber in his account of the 1660 journey to the Levant by the knight Laurent d'Arvieux. Ristelhueber wrote: "Then he went to the patriarchal seat of Qannoubine, where Monsignor George of Bsebeel received him with great honors. Tall, blond, with a countenance both cheerful and dignified. The patriarch was possessed with wit and refined and engaging manners. D'Arvieux was pleasantly surprised to see, in the sacristy, a large portrait of Louis XIV."

His epitaph carved in the rock medallion reads: "Glory to God. Here rests George Peter, Patriarch of Antioch of the Maronites, of Bsebeel. In the year of the Lord 1670, on the 12th of Nisan (April)."

From 1276 to 1628

The sculptor demonstrated great skill, both in his command of the Syriac language, its syntax, and in the quality of the carving. The letters are fluid and dynamic. The medallion organically curves upward to include a cross. The text uses typical Syriac abbreviations to fit the circular shape: téchbou for téchbouhto (glory), patri for patriarko, and d'Antio for d'Antiokia.

Three hundred and fifty years separate us from the last medieval Maronite epigraph, that of Our Lady of Ilige, dated 1276--77 and the new inscription at Mar Chalita of Ghosta, dated 1628, which marks the beginning of a renaissance Lebanon was to experience under Ottoman rule. These two epigraphs are among the finest in their calligraphy, whether in Estrangelo or Serto script, and both demonstrate a remarkable mastery of the Syriac language and stone carving.

Dr. Amine Jules Iskandar is an architect, teacher, President of the Syriac Maronite Union -- Tur Levnon and Head of External Relations of the Syriac Union Party in Lebanon.

or register to post a comment.