Whether you're someone who checks the bitcoin price live daily or just curious about cryptocurrency's origins, there's something fascinating about tracing these technologies back to their roots. So here's something remarkable - archaeological evidence shows that Mesopotamian scribes developed immutable record-keeping systems around 3400 BC, complete with distributed verification networks and sophisticated authentication protocols. Their records were not just primitive scratches on rocks, they incorporated similar checks that are used in blockchain technology today, but in a very different form. These tablets were comprehensive systems managing complex economies across vast empires.

The Library of Ashurbanipal alone contained over 30,000 tablets. That's more documentation than many modern companies produce in a year. The Mari archive of 15,000 texts dating from the Amorite period tracked 160 separate kingdoms over just three decades. This is large scale accounting documentation.

The Original Immutable Ledger

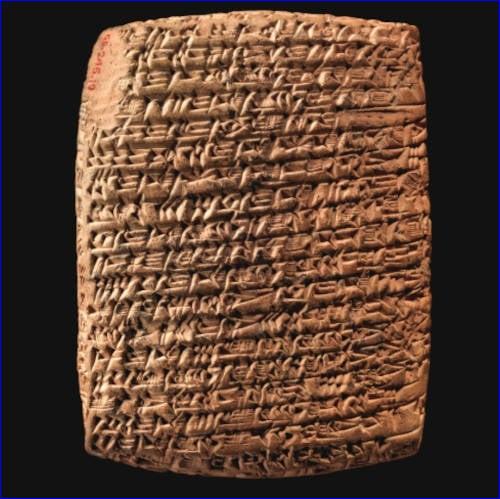

Let's start with something that might surprise you. Those ancient clay tablets weren't just convenient writing surfaces, they were deliberately engineered for permanence. Mesopotamian scribes fired their most important records in kilns, creating what they called "eternal records". Once fired, these tablets became virtually indestructible. Many have survived over 5,000 years, which is more than we can say for most digital storage formats from the 1990s.

The tamper-evident properties were ingenious. They used bullae - clay envelopes sealed around important documents. Without breaking the seal, you could not examine the contents, making any unauthorized alteration completely obvious. It is the ancient version of today's blockchain cryptographic hashing, since any change to the record is immediately discernible as tampering.

Now here is where it gets interesting. The Mesopotamians weren't just creating immutable records, they were resolving the same trust problems blockchain solves today. How do you create records that can't be altered without detection? How do you verify transactions without relying on a single authority? These questions drove innovation then just as they do now.

Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Scribe Network

Now we get to the really clever part. The Mesopotamian record-keeping system wasn't centralized - it was distributed across a network of professional scribes working from "palace and temple to the modest village or farm". These weren't just clerks; they were highly educated specialists who formed "a considerable part of the governing bureaucracy" in Assyria.

This network operated on consensus principles. Commercial transactions required multiple witnesses and had to be "recorded in clay and witnessed". No single party could alter important records without detection because copies existed across multiple locations, maintained by different scribes. Sound familiar?

The geography of the records was remarkable. We see large records in Nineveh, Ebla, Mari and Uruk and clear evidence that they were consciously collecting records across the ancient Near East. These scribes were not found on islands; they kept records and were using an organized and co-operative system, synchronizing records across distance.

What is most striking is how they went about verifying these records. The Code of Ur-Nammu goes back to about 2100 BC and appears to clarify the methods of loans, business transactions and public interest rates. These legal frameworks were the basis of how these transactions were verified and chronicled. This became a sort of layer of protocols for communicating through their distributed system.

Seals, Signatures and Security

Here's where ancient accounting technology gets truly sophisticated. Cylinder seals, dating back to 4,400 BC, functioned as the world's first personal authentication devices. These weren't ceremonial objects - they were practical tools used "at all levels of society," not just by royalty.

Each seal created a unique impression when rolled onto clay tablets, serving as an unforgeable signature. The process was remarkably similar to modern cryptographic signatures: possession of the seal plus knowledge of its proper use authenticated the owner's identity and intent.

The Mesopotamians even had multi-factor authentication!

- Something you have (the cylinder seal itself, usually worn as jewelry)

- Something you know (who can understand what the different designs and seals mean on the personal seal)

- In-person witness verification (transactions were confirmed in plain sight for multiple people)

- Some early use of biometric components (e.g. fingerprints pressed into clay tablets by 500 BC)

This multi-layered approach created strong security. Each party to a loan or deposit would mark the tablet with their unique seal, ensuring the agreement was recognized. It's a surprisingly modern approach to identity verification.

From Cuneiform to Cryptocurrency

Here's what this means for us today. Blockchain technology is not a radical shift in human history. It's just the latest episode in our ongoing quest to create reliable records. The problems we are trying to address using distributed ledgers are the same problems ancient societies experienced: how do you generate a lasting, verifiable record without a trusted centralized authority?

The Mesopotamians adapted to these challenges by using fired clay, sharing scribe networks, and advanced validation mechanisms. We are adapting to them with cryptographic hashing, peer-to-peer networks, and digital signatures. The technologies change, but the challenges are ageless.

Perhaps that's the most surprising and meaningful aspect here is how our digital future is tied intimately to our ancient past. The very principles behind blockchain were tried and tested for thousands of years before our first line of code was ever written.

or register to post a comment.