The story behind this find isn't just about its age but the biological treasure trove it held within.

The Discovery

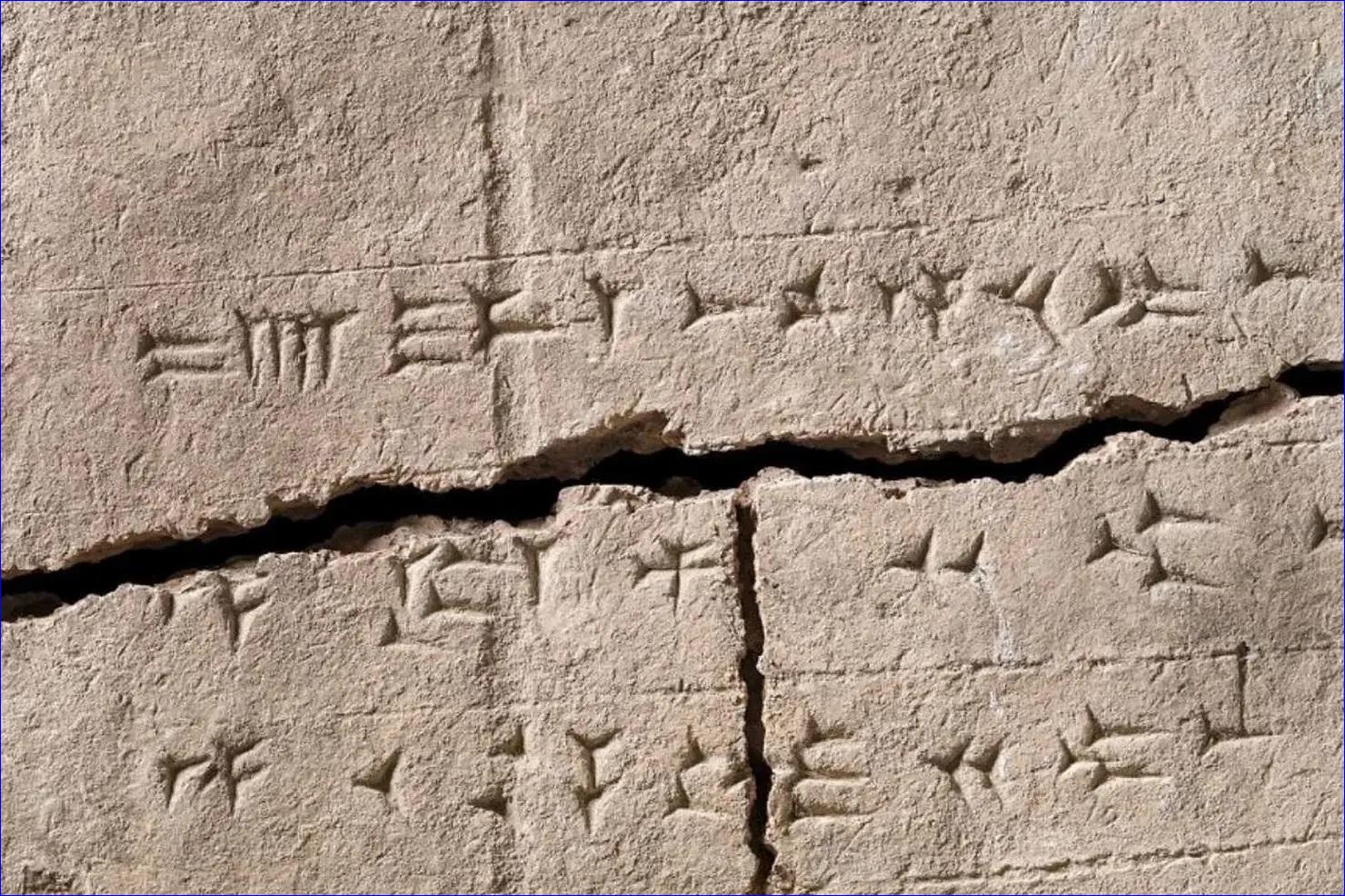

Found amidst the ruins of a palace in modern-day Iraq, this brick dates back to the era of the Neo-Assyrian king, Ashurnasirpal II. Researchers swiftly dated the artifact thanks to inscriptions etched on its surface, revealing its creation between 879 - 869 BC. Intriguingly, these dates coincide with what is believed to be the construction period of the palace where it was discovered.

What's intriguing is the context. Historical writings, including hieroglyphics, suggest that such bricks were molded using mud from the Tigris River. Taking a cue from ancient descriptions, even from as far afield as Egypt in the Bible, they were often made by mixing river mud with straw and other organic matter.

The Biological Time Capsule

Upon closer examination, it was discerned that the brick contained remnants of plants and traces of animal dung. This ancient composite offered researchers a unique window into the past, enabling them to reconstruct the vegetative and floral life of that period. It was like holding a piece of the Neo-Assyrian epoch in one's hands.

This pioneering study saw collaboration from renowned institutions: the University of Oxford, the University of Copenhagen, and the National Museum of Denmark. Together, these researchers identified an astonishing 34 different plant species embedded within the brick.

Sophie Lund Rasmussen, the lead researcher from the University of Oxford, expressed her amazement, commenting, "It's truly remarkable how a simple brick could act as a time capsule, preserving ecological artifacts from millennia ago."

The key to this preservation, she explains, lies in the very methods of brick-making. Modern bricks, baked in high-temperature kilns, obliterate any biological content. In contrast, ancient bricks, often left to dry naturally under the sun, preserved the genetic imprints of organisms within them.

A Snapshot of Ancient Biodiversity

Troels Arbøll, an Assyriologist from the University of Copenhagen, concurred with Rasmussen, emphasizing the immense value of the find. "The DNA analysis of this ancient brick offers us an unparalleled glimpse into the biodiversity of a typical ancient Assyrian community," he noted.

Within the matrix of the brick, researchers identified an array of plants, including cabbage, birch, mustard, laurels, and monocotyledonous grasses, suggesting the likely presence of wheat. The fact that animal DNA, particularly from dung, was better preserved became another exciting avenue for exploration.

The Power of Collaboration

The achievements of this study underscore the incredible outcomes that can emerge from interdisciplinary collaboration. Had it not been for the unique fusion of expertise from archaeologists, biologists, and historians across various institutions, the intricate details and insights gleaned from this brick might have remained undiscovered.

In essence, this ancient brick, a seemingly ordinary object, has bridged the gap between the present and a time 2,900 years ago. Its discovery and the subsequent revelations stand as a testament to the ever-evolving, ever-surprising field of archaeology, reminding us that sometimes, profound secrets are hidden in the most unexpected places.

or register to post a comment.