Michelson coedits four online reference works that make Syriac history and literature accessible to scholars and students worldwide. His previous book focused on the Syriac theologian Philoxenos of Mabbug, a prominent figure among opposition to the Council of Chalcedon in 451. Michelson's latest work, The Library of Paradise, examines a monastic tradition of contemplative reading among such non-Chalcedonian Christians during the sixth and seventh centuries.

Reading in order to connect more deeply with God not only has a long history, but it remains a valued aspect of Christian spirituality across several traditions. Such contemplative reading has been popular among small groups and individuals in evangelical circles. But Michelson explains that the better-known Benedictine practice of lectio divina shares origins with the contemplative reading done by East Syrian monks. Each developed separately into its own tradition.

And yet, in light of Christianity's relative disappearance in modern Syria, its growing cultural decline in Europe, and hardening ideological divisions in both Europe and the United States, the question must be asked regarding Michelson's chosen topic: So what? Isn't monastic life an escape from the real world? Don't we read either to glean needed information or pass a few precious moments of unoccupied time? What possible value might contemplative reading as practiced long ago and far away have for a world like ours? These last two questions, in particular, merit reflection.

Although there is a common assumption that everyone in the Greco-Roman world spoke Greek and Latin, many other languages were spoken. Syriac was among the more prominent of them. Most writing from the later Roman Empire that remains available to us was produced in Greek or Latin, but Syriac writings make up the next largest number of surviving texts, Michelson notes. The continued study and preservation of these languages is vital for developing a more complete knowledge of history, thought, and culture in the Mediterranean world of late antiquity. For these reasons, it is also important to understand how such writings were read, understood, and used at particular times by specific individuals or groups. This is only beginning to be the case when it comes to the study of Syriac writing. Michelson's contribution lies in his focus on the unique tradition of reading Scripture and other spiritual literature that developed among Christian monks associated with the Church of the East just before the coming of Islam.

But what is "contemplative ascetic reading," as Michelson defines it? It is tempting to assume it is simply identical to lectio divina. But this view cannot be justified for two reasons, according to Michelson. First, lectio divina is a Latin, therefore Western, label; but precise understanding of East Syrian ideas and practices requires that we avoid relying on Western categories when studying those that are non-Western in origin and character. Following from this, the independent development of these two different kinds of spiritual reading--East Syrian and Western--means that using the same terminology to describe each type risks blurring real differences between them.

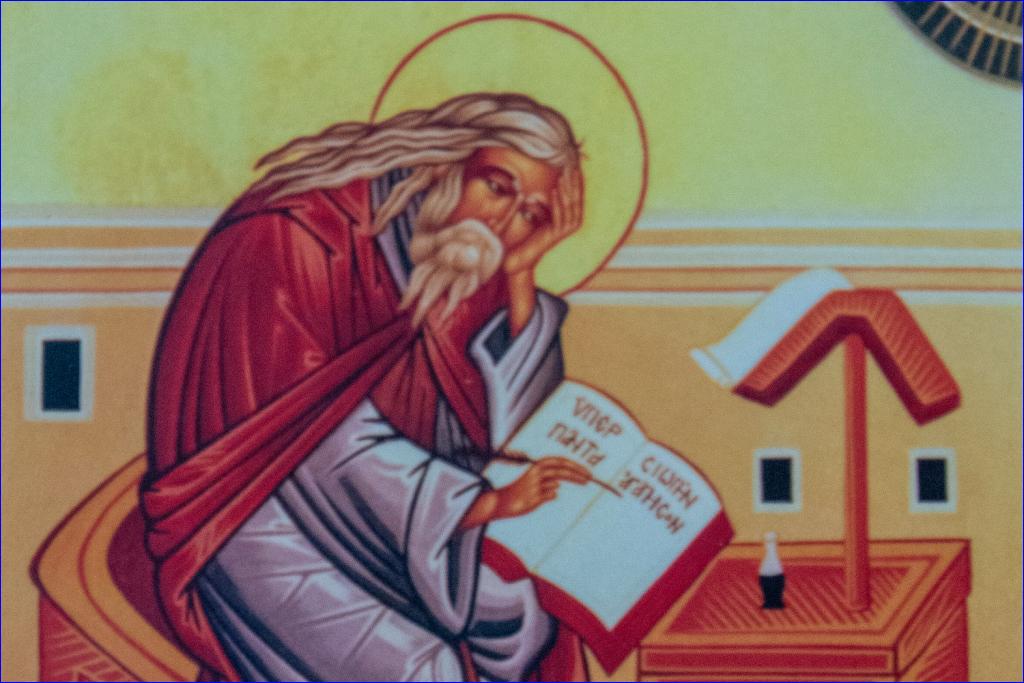

Even the idea of reading itself should be understood carefully as its possible range of meanings in Syriac includes such diverse practices as silent meditation, prayer, or singing and chanting--in addition, of course, to the act of reading a physical book. All such forms of reading were practiced as spiritual disciplines whose purpose was to know God intimately, rather than to absorb or intellectually process information. As a result, "contemplative ascetic reading" encompasses a number of East Syrian monastic reading practices that functioned within a tradition originating with fourth-century monk and theologian Evagrius of Pontus and developing through the seventh century in works of such monastic thinkers like Isaac of Nineveh.

One does not need to be a scholar to appreciate the significance of Michelson's efforts to ensure that our knowledge of East Syriac monasticism and its reading practices continues to grow. Just as some contemporary evangelicals have sought spiritual nourishment in the Western practice of lectio divina, so there is the possibility of Western Christians engaging with the wisdom and experiences of East Syrian Christians who read in their way as a means of coming closer to God. Not everyone will choose (or be able) to learn Syriac, but through the work of scholars like Michelson we are exposed to unfamiliar ideas and practices that potentially enrich our perspectives while deepening our spiritual lives.

Furthermore, faithful commitment to one's particular Christian expressions and forms does not have to involve total rejection of all others--such as the contemplative reading practices of different Christian traditions. Without the capacity to balance change and continuity demonstrated by the ancient East Syrian monks discussed in this book--to say nothing of Jesus, Paul, Augustine of Hippo, Martin Luther, or John Wesley--Christianity would be impoverished significantly.

Andrew J. Pottenger holds a Ph.D. in church history from the University of Manchester. He is the author of Power and Rhetoric in the Ecclesiastical Correspondence of Constantine the Great (Routledge, 2023).

or register to post a comment.