Erin O'Brien)

Erin O'Brien)

But we weren't there for the jewelry, nor the coffee. We were there for the wine.

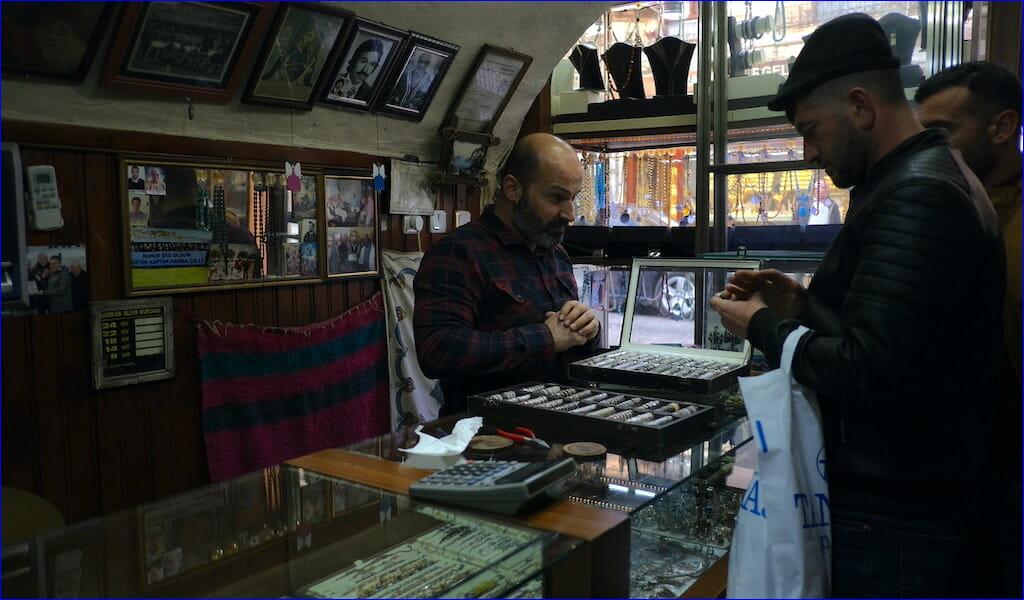

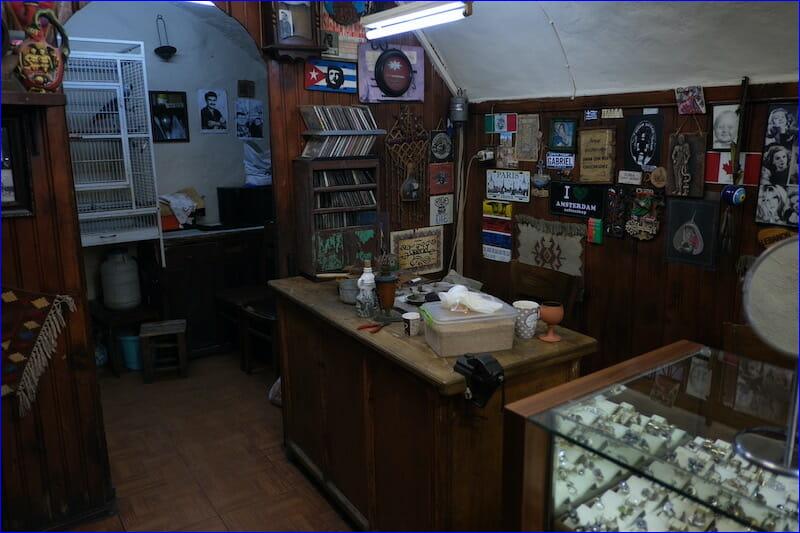

Gabriel sells homemade Assyrian wine out of the back of his silver shop, aptly named "Gabriel Silver and Gold." This wine, called "Mardin Suryani Sarabi," is slightly sweet, slightly spicy, and like nothing we've ever tasted before. The first time we had it, a filmmaker friend who had a key to the shop let us in, we took a bottle, left cash on the counter, and drank the wine out of plastic cups on a rooftop looking out towards the lights of Syria. The second time, we chatted with Gabriel about his childhood in Mardin, his travels around the world, and his final return to his ancestral homeland, the ancient city. And this time, we settled in with a glass of wine each while he told us how he came to this ancient trade.

Winemaking dates back millennia in Mardin -- many historians and archaeologists believe that winemaking began in the region, the Mesopotamian plain, over 2,700 years ago. The Assyrian community's name derives from the Assyrian empire, a polytheistic empire that ruled a vast swath of land spanning Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria from 2500-609 B.C. The Assyrian community has carried down many practices begun by the empire -- including jewelry making, silversmithing, and winemaking.

During the Ottoman Empire, like other non-Muslim groups, Assyrians continued to live and practice their religion -- Christianity -- in the southeastern regions of what is now modern Turkey in return for taxes paid to the Ottoman state. This system of cohabitation continued until the final years of the Ottoman empire, when thousands of Assyrians, along with Armenians and other Christians, were murdered and displaced. The Assyrian genocide of 1915 -- considered by the community distinct from the Armenian genocide -- is referred to as the Sayfo, and according to Assyrian delegates that attended the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, over 250,000 Assyrians were murdered. The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO) estimates the number of those killed between 1915 and 1918 far higher, at 750,000.

According to Minority Rights Group International, approximately 95% of Turkey's Assyrian population has left the country as a result of the genocide and ongoing violence against the Assyrian community after the foundation of the Turkish republic. Just 3,000 Assyrians are estimated to still live in their ancestral homeland, the southeast provinces of Sirnak, Hakkari, and Mardin, while an estimated 22,000 live in Istanbul. Those that remain, like Gabriel, strive to maintain practices that all but disappeared with the campaign of violence against his community -- including winemaking.

Erin O'Brien)

Erin O'Brien)

Modern Assyrian winemakers have worked to integrate new winemaking techniques with ancient grapes and practices. When he was growing up, Gabriel remembers his Uncle Suphi making wine for the family and community. Later, his father, Hanna, continued the practice. The two men -- who learned the technique from Gabriel's grandfather -- would harvest ancient grape varietals from the vineyards around Mardin, crush them, then let the grape juice oxidize before bottling and storing the wine to be opened on holidays. That oxidization period is what lends Assyrian wine its specific taste.

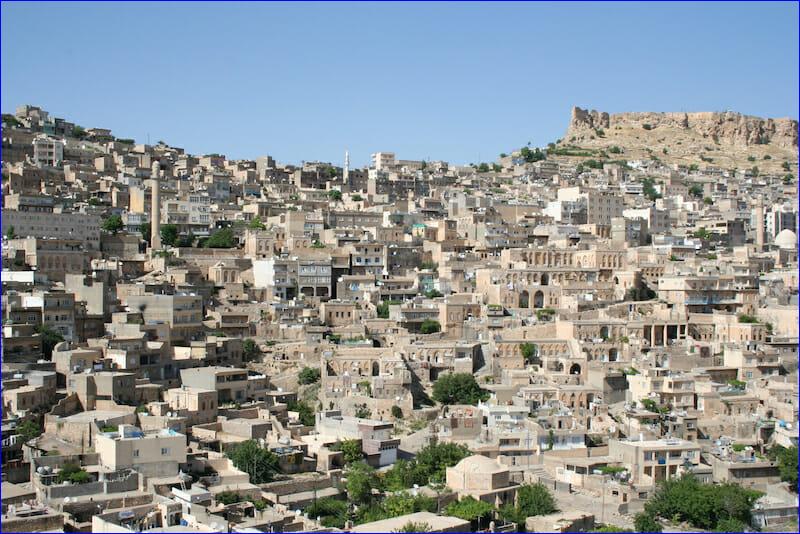

For much of the last century, this was how the wine was made and consumed -- by the community, for the community. However, the past two decades have seen the rapid rise of tourism in Mardin and with it a taste for Assyrian wine. Now, the main street through the old city, lined by intricately carved sandstone buildings, is dominated by shops selling the beverage, along with the yellow bittim soap and silver jewelry for which the city is famous. Tourists flock to the sandstone city, perched on a hill, for its ancient sites and leave with bags full of Assyrian wine and pastries -- remnants of a culture practically disappeared.

Erin O'Brien)

Erin O'Brien)

Despite the rise in the popularity of Assyrian wine, Gabriel has maintained the ancient techniques used by his ancestors. He still uses indigenous grape varietals -- many of them cultivated by the Armenian community which existed in the region before the 1915 genocide -- that his family worked to protect. He still crushes the grapes by hand and leaves them to oxidize in the sun in large vats. He estimates that he makes around a thousand bottles every year like this, foregoing a factory for a smaller-scale production warehouse outside of Mardin's old city.

He's integrated the winemaking technique he learned from his family with the techniques of European masters. When he returned from military service to Mardin when he was twenty, he realized that his family's wine could turn a profit. He began taking classes in winemaking and brought his professors to Mardin. They made it more "professional," Gabriel said, and allowed him to produce more and consistently better-quality wine. He also began sourcing grapes to add to his family's repertoire, including more indigenous varietals long believed to be lost.

What resulted is Gabriel's spicy, sweet Assyrian wine, the one we drank out of small earthenware cups that cold day in January. Years -- centuries -- of honing produced a wine that warmed us with its richness, tickled our palates with its surprisingly complex flavor, helping us to fend off the bitter cold that crept at Gabriel's door, the winter wind that whistled through Mardin's empty, narrow streets.

The work of maintaining a cultural tradition, like Assyrian winemaking, does not happen without difficulties. Under the AKP-led government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, alcohol producers generally and winemakers, in particular, have faced increasing scrutiny and limits on production and advertising. Small producers like Gabriel and others in the region struggle to be approved for government-sanctioned labels. With a full ban on advertising alcohol in the country, they primarily rely on word of mouth to sell their wares. Gabriel believes that his wine business would be unable to survive without the income he earns from jewelry making and piercing.

Erin O'Brien)

Erin O'Brien)

Turkey is also in the midst of a historic economic crisis -- the Turkish lira has lost over 30% of its value against the dollar since the beginning of the year. Inflation is officially at a two-decade high of 73.5% (though experts estimate that, in actuality, it is far higher). Nearly all of the materials Gabriel uses to make his wine -- corks, bottles, barrels -- are sourced from abroad, so as the lira loses value, the cost of making the wine increases. Gabriel tries to keep his prices low for loyal customers but has had to raise them, as have all winemakers in the country.

There is also climate change to contend with. The region around Mardin is in the midst of a historic drought, with dams and lakes drying up in record-breaking heatwaves. While the grapes Gabriel uses are somewhat resistant to the heat -- they are native to the area and therefore can survive a degree of battering from the region's harsh climate -- the extremes Mardin is experiencing are threatening even the most rugged of grapes. For now, Gabriel's dry-farming practices, which do not require additional water, can withstand Mardin's ever-warming climate. But if things get much worse, he says, he'll have to consider changing his harvest times or relocating to different vineyards.

In the face of these manifold difficulties, Gabriel is disappointed that there is less cooperation among winemakers and between winemakers and the government. Few grape growers employ data-driven or "intelligent" farming practices, he says, and even fewer share their learnings. There is little price cooperation and coordination, and the government provides no incentives or tax breaks to winemakers. There isn't even a centralized weather data collection system where producers can access detailed climate data. This has hobbled the wine industry, including those making Assyrian wine.

To him, the government's position towards alcohol and winemaking needs to change if winemakers in Turkey have any hope of survival. Taxes on alcohol have increased and continue to do so -- last month, alcohol taxes in Turkey were raised by 25% after already being raised nearly 50% at the start of the year. Further, the government needs to collect and distribute data to support and encourage smart farming practices. If people were to be more efficient when growing and harvesting grapes, Gabriel said, the wine industry would be more sustainable.

Unfortunately, he doesn't see this kind of support happening while the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) is still in power.

"Wine is a culture," Gabriel said, "Unfortunately, they don't see it that way."

or register to post a comment.