Courtesy of the Artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago)

Courtesy of the Artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago)

When Western audiences imagine artwork from this region, carpets often first come to mind. One of the most extraordinary examples of which can be seen now at the Aga Khan Museum, 15 minutes outside of downtown Toronto.

The Wagner Garden Carpet makes its first ever appearance in Canada through January 17, the last stop on a three-city tour that also included the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A rarely-travelling masterpiece of Islamic art, this monumental carpet--over 13x16 feet--made in 17th-century Kirman, Iran, is one of the oldest surviving Persian garden carpets.

Considering its size, age, craftsmanship--each square centimeter has about 100 individually hand tied wool knots--and near pristine condition, the object is a true wonder.

Slipping into the lush, green garden teeming with life portrayed, visitors discover the origin of the word "paradise."

"The English word for 'paradise' comes from the ancient Persian term 'pairidaeza,' meaning walled garden," exhibition curator Dr. Filiz Çakır Phillip explained to Forbes.com. "The classical Iranian garden with water courses is called 'chahar bagh;' following this tradition, the Wagner Garden Carpet has two long, parallel water channels linked by a central pool and two short tributaries, together, they form the shape of the letter 'H' and create four rectangular sections, dividing the carpet in six sections."

Named after a German collector who acquired it in the early 20th century, the Wagner Garden Carpet was bought by Scottish shipping magnate Sir William Burrell in 1939. Because of the carpet's size and the restrictions Burrell placed on it, it's only been out of storage and on public display three times in the past 20 years.

Seen on the carpet, a wonderland, a paradise.

"The imagery of the Wagner Carpet is a merry mix of garden and forest vegetation accompanied by an amazing variety of wildlife busy with life and activity," Çakır Phillip said. "The richness of floral and figurative elements in carpets is fascinating, for example, the peacock--you will discover that this paradise bird is repeated many times --if you look closer, you will see that the tails of these birds, sometimes up, sometimes down, show a range of artistic creation... don't forget to look for bugs and butterflies."

Natural dyes like indigo (for blue), madder (for red), leaves and flowers (for yellow), and iron-rich muds and tree barks (for browns and blacks) gave the carpet its brilliant colors.

The Aga Khan Museum dedicates itself to providing visitors with a window into the artistic, intellectual and scientific contributions of Muslim civilizations. These are lessons sorely lack in America where great confusion still exists regarding Islam.

"Generally speaking, there is a misconception that Islamic art is purely religious or only for Muslims," Çakır Phillip said. "The notion of 'Islamic art' was invented by Western scholars who were trying to understand it within the Western parameters familiar to them."

According to Çakır Phillip, Islamic art is divided roughly into two general styles: a style for the religious context, including architecture (mosques, madrasas, etc.) and texts (Quran manuscripts, prayer books, etc.); and a style for the more secular context, which can be described as courtly as well.

"The latter allows artists to express themselves using geometric patterns, both floral and abstract, but also using figurative elements," she said. "There is no 'aniconism' (forbidding of material representations) in Islamic art; naturally, no artist would include figurative elements while illuminating a Quran manuscript, for instance."

Additional discovery can be made at the MFA, Houston, where a unique cultural exchange nears completion.

The Museum's landmark partnership with the Kuwait-based al-Sabah Collection and the cultural institution Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyyah wraps up on December 27. Until then, an expanded installation of "Arts of Islamic Lands: Selections from The al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait," greets visitors.

The al-Sabah Collection is one of the greatest privately held collections of Islamic art in the world. The collaboration with the Museum, established in 2012, led to the 2013 Houston debut of 67 objects ranging from carpets and architectural fragments to exquisite ceramics, metalwork, jewelry, scientific instruments and manuscripts.

This expanded installation more than triples the display, increasing the art on view to some 250 works. Objects from the 8th to 18th century--made in North Africa, the Middle East, Turkey, India, the Iberian Peninsula and Central Asia--demonstrate the development of techniques, craftsmanship and aesthetics in Islamic visual culture.

Atlanta's High Museum of Art draws upon another private collection of materials for its exhibition, "Bestowing Beauty: Masterpieces from Persian Lands."

Organized by the MFA, Houston, with the work on view coming from that institution, this show, which opens on December 12 and runs through spring 2021, brings together nearly 100 examples highlighting the rich and artistic cultural heritage of Iranian civilization from the 6th to the 19th century.

Pieces on view include carpets, textiles, manuscripts, paintings, ceramics, lacquer, metalwork, scientific instruments and jeweled objects. Highlights include exquisite miniature paintings from the Shahnama, the Iranian national epic.

From ancient Iranian artistry to contemporary, Amir H. Fallah (b. 1979, Tehran), takes on a major mural commission at the Institute of Contemporary Art in San Jose, California.

The institute debuts "The Facade Project"--an ongoing public art program dedicated to exploring the most critical social and political issues facing our time --with Fallah. The initiative will feature artists whose identities and work represent areas of the global community that have been largely overlooked by American arts institutions, thereby, offering a course correction to past patterns of inequity within the museum system.

"Amir H. Fallah: The Facade Project" includes a 50-foot mural enveloping the front of the building.

Fallah presents text and images from children's books interspersed with visual quotations from Persian miniatures, illuminated manuscripts, American propaganda imagery and widely dispersed paraphernalia.

The most challenging presentation comes from the Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College in Clinton, New York with the exhibition, "Michael Rakowitz: Nimrud."

Rakowitz, a descendant of Iraqi Jews, takes on the region's history of cultural abuse from both Western relic hunters and Muslim extremists using the once magnificent Room H from the Northwest Palace of the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud (formerly known as Kalhu) as his example.

"The Northwest Palace was a sprawling palace and administrative center built in the ancient city of Kalhu by Ashurnasirpal II (King of Assyria from 883 to 859 BCE), who had designated the city as the capital of his empire," Katherine Alcauskas, curator of the exhibit, told Forbes.com. "The walls of the palace were lined with stone into which was carved bas-relief imagery and an inscription stating the King's might and many great deeds, all then painted in bright colors."

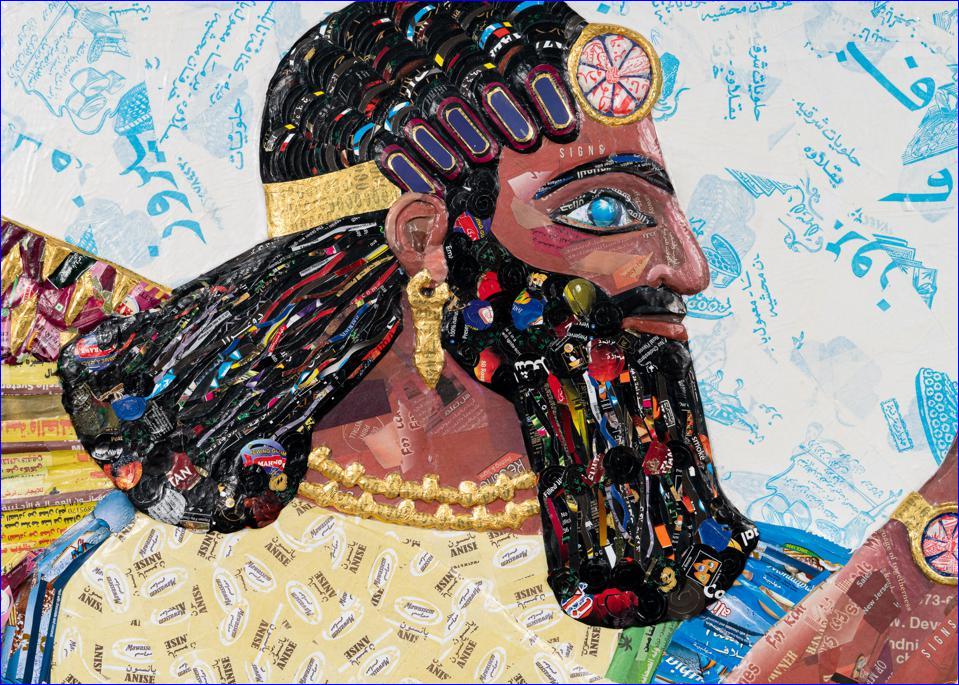

For this exhibition, Rakowitz has re-created only those stone panels, 7-feet-high, using Arab-language newspapers and wrappers from food products imported from the Middle East and sold in specialty grocery stores in Chicago where the artist lives.

"In the middle of the nineteenth century, British archaeologists, along with American missionaries and others, uncovered the reliefs and dismantled them, sending a majority to institutions in England, France and America," Alcauskas explains. "The reliefs in this palace, along with a couple others in the ancient Assyrian empire, are often taught in college-level survey courses as foundational artworks in the history of the field."

Nearly 400 of the 600 Assyrian reliefs were removed from what is now Iraq and were acquired by private collections and public institutions throughout the Western world, such as the British Museum, London; Musée du Louvre, Paris; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Brooklyn Museum; Yale University Art Gallery; and numerous small liberal arts colleges in the northeastern United States, including Hamilton College (a stele now in the Wellin's collection entered the College's collection during that period).

"Rakowitz's work implicates the museum as a colonial entity and calls attention to the paradoxical mission of preserving damaged and incomplete objects, arresting their function and immobilizing their historic context," Alcauskas said when announcing the exhibit which debuts at a reopened Wellin, October 19 and runs through June 13, 2021. "It also underscores the different treatment granted to refugees versus 'treasures' of art history; whereas museums across the United States might readily accept artifacts into their collections, paradoxically immigrants are not as welcome in the country itself."

Destruction of the Northwest Palace wasn't completed when the Western scholars exited.

The remaining 200 reliefs were destroyed by ISIS in 2015, claiming it was done for reasons of religious purification--that the reliefs were irreverent in their acknowledgment of or celebration of polytheism, as the ancient Assyrians had practiced. It has also been observed, however, that ISIS viewed archaeology as a foreign import that supported Iraqi nationalism, which countered its own goal of a unified Islamic state under the rule of a Muslim leader.

For this exhibition, Rakowitz has re-created only those panels that were in situ in Room H from the Northwest Palace prior to its destruction by ISIS. Areas from which the reliefs had already been removed by 19th century archaeologists are left blank.

The questions presented by Rakowitz bear keeping in mind when visitors are allowed to return to the Getty Villa in Los Angeles which remains closed, but will continue to present "Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins," (through summer 2021) and "Assyria: Palace Art of Ancient Iraq," (through summer 2022) when it reopens.

The "Assyria" exhibition features palace relief sculptures on loan from the British Museum.

or register to post a comment.