Carole Raddato, Frankfurt, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Carole Raddato, Frankfurt, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0)

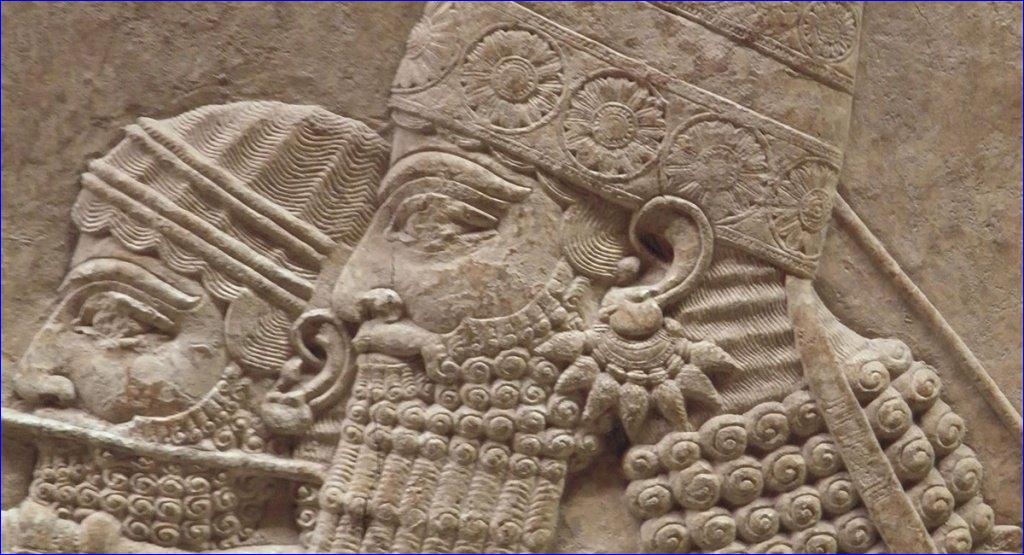

A bas relief of Assyrian King Ashurbanipal, who reigned in the 7th century BCE, serves as a great propaganda piece for the ancient ruler--mostly. Ashurbanipal is shown saving his kingdom from a pride of lions over and over, on horseback and in a chariot, as an archer and with a lance. However, one panel of the sculpt betrays the others, as it shows a choreographed release of lions, indicating the entire portrayed event was staged.

Ashurbanipal was an intellectual king who owned one of the first libraries in recorded history, including a copy of the poem The Epic of Gilgamesh. In her video series Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization, Dr. Amanda H. Podany, Professor of History at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, described his collection of literature.

A Mind That Thirsted for Knowledge

According to Dr. Podany, Ashurbanipal was one of the few kings of his time who not only could read and write, but who also studied with local scholars. In his palace at Nineveh, which is in modern-day northern Iraq, he collected vast amounts of written work that had been transcribed on clay tablets, enabling them to survive millennia.

"When the library was rediscovered during the mid-19th century excavations, these same writings provided scholars with an extraordinary window into the intellectual world of the neo-Assyrians," she said. "The discovery of Ashurbanipal's library at Nineveh created front page headlines once its contents began to be revealed. Nineveh was of great interest in the new field of archaeology, because it had been the fourth and largest capital of Assyria."

Nineveh had become the capital shortly before Ashurbanipal rose to power, and it remained there for the rest of the neo-Assyrian empire.

After Ashurbanipal became king in 668 BCE, he sometimes boasted about his intelligence and wisdom. He understood and debated scholarly texts, solved advanced mathematical problems, and could translate from Sumerian, which was already a dead language by the time of his rule.

"All of this tells us that Ashurbanipal was deeply interested in scholarly learning, and as a result, he was singularly focused on the creation of his library," Dr. Podany said.

The Great Library

wasn't meant for the public; he simply collected written works for his own use and that of his court.

"Yet it didn't include much of what you'd expect in a library, like works about history or current events or scientific discoveries," Dr. Podany said. "Still, the shelves of Ashurbanipal's library were lined with tablets representing the most advanced knowledge of the time--knowledge useful to the king.

According to Dr. Podany, there were lists of words used by scribes in schools as well as royal inscriptions from the past. There were also rituals and hymns, some of which were written in Sumerian; and descriptions of medical conditions and the ways to treat them. Finally, there were thousands of "omen texts" which described peculiar events and things believed to happen in their wake.

When the library was rediscovered in the 1850s, its contents were shipped to the British Museum in London, where they remain and are studied to this day.

or register to post a comment.