Yaniv Berman/IAA)

Yaniv Berman/IAA)

In late July, the Israel Antiquities Authority announced the results of a much more thorough excavation conducted on one of these mysterious mounds. Under this one, archaeologists uncovered remains of a 2,700-year-old building and dozens of stamped jar handles, indicating the site was likely connected to the administration of the Kingdom of Judah in the First Temple period.

But while the findings are fascinating and bountiful, they raise more questions than they answer. Why was an administrative center from biblical times buried under a humungous heap of stones and soil? And were similar coverups the reason why the other mounds nearby were built?

Haaretz has spoken to top archaeologists who have studied these ancient structures in an effort to reconstruct their story and understand the main theories that try to explain them.

Philistines in Jerusalem?

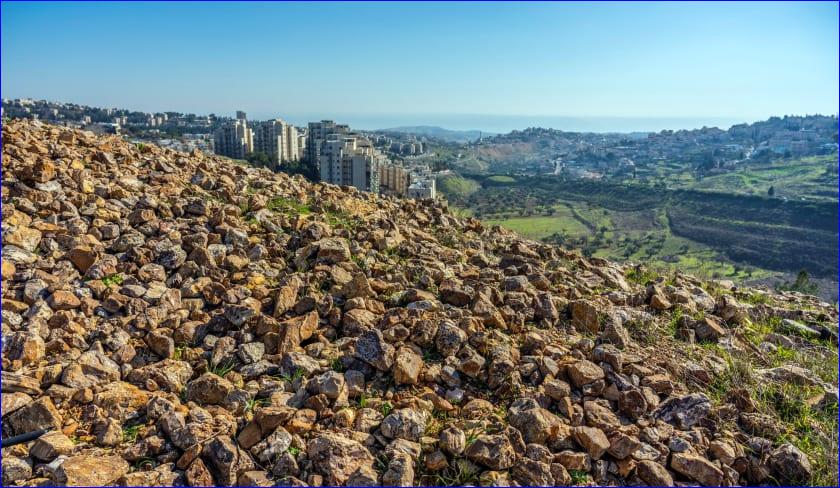

Since the second half of the 19th century, when the British surveyors of the Palestine Exploration Fund began studying the Holy Land, at least 19 artificial mounds, or tumuli, have been identified to the southwest of the Old City of Jerusalem.

Most are clustered in a fairly small area of a few square kilometers, mainly on the ridge overlooking the biblical Valley of Rephaim -- a proximity that has led archaeologists to read them as a unified phenomenon, whatever its significance may be. Today, some of the tumuli have completely disappeared while others are surrounded by modern Jerusalem's urban sprawl.

The recently completed dig by the IAA on the tumulus in the neighborhood of Arnona was in fact conducted ahead of construction of new housing units in the area. But for most of their history, these imposing mounds would have been on open ground in the periphery of the ancient city and surrounded by farmland, a fact that features prominently in some of the interpretations given by contemporary archaeologists.

"Their concentration in a very specific area and the huge effort required to raise them makes it very unlikely that these were just garbage dumps or heaps of stones cleared from agricultural fields," says Yuval Baruch, the IAA's chief archaeologist for Jerusalem. "But the question of why they were built remains. Over the last century many theories have been put forward, each with its own merits and weak points."

One of the first investigations of the enigmatic cairns was conducted in 1923 by William F. Albright, a U.S. researcher considered the father of biblical archaeology. It was Albright who involuntarily gave one mound, today surrounded by the modern neighborhood of Givat Massuah, the shape of a tush. In his brief, five-day excavation, Albright did not find a structure or tomb under the heap of stones, but he still compared the Jerusalem tumuli to early Iron Age burial mounds found in Greece.

Based on pottery shards from his trench, Albright dated the tumuli to the 11th century B.C., during the supposed time of the prophet Samuel, and kings Saul and David. He speculated however that the tumuli were raised not by the Israelites but by invading Philistines, possibly because already then archaeologists suspected these people had a connection to the Greek world.

Today, most experts reject Albright's dating of the sites, nor is there any evidence that they were tombs or that the Philistines had anything to do with them.

Pagan sites or royal memorials

A more in-depth study of the tumuli was conducted in 1953 by Israeli archaeologist Ruth Amiran, who surveyed several mounds and completely excavated one of them, just outside the neighborhood of Kiryat Menachem. She found that this tumulus concealed a retaining ring wall interrupted by a flight of a few steps. These led onto a platform that housed remains of a fire and burnt animal bones. Amiran identified the pottery shards from the mounds she studied as being typical of the Kingdom of Judah in the late 8th and 7th centuries B.C.

Based on these findings, she suggested that the mounds may be identified with what the Bible calls "bamot" - usually translated as "high places." These were hilltop locations of worship that were supposedly destroyed in the reforms of kings Hezekiah (2 Kings 18:4) and Josiah, (2 Kings 23:5) as they attempted to centralize cultic practices at the Temple in Jerusalem and make the Israelite religion more monotheistic.

Amiran's dating of the mounds does sit well with the reigns of Hezekiah and Josiah, who sat on the throne of Jerusalem in the late 8th century B.C. and the second half of the 7th century B.C., respectively. Subsequent digs of other mounds have indeed dated them to this period, but the idea that the tumuli were raised in order to cover up places linked to religious beliefs that were no longer acceptable is met with skepticism by archaeologists today.

For one thing, not all the tumuli have been shown to cover platforms or other structures. For another, if the intention was to tear down pagan shrines and erase their memory, it seems counterproductive to do so by raising mounds that were visible from miles away and would remain standing for thousands of years.

Another theory that attempted to use the biblical narrative to explain the purpose of the mounds was published in 2003 by Bar-Ilan University archaeologist Gabriel Barkay in the Biblical Archaeology Review. Based on the similarities with mounds that have been excavated in Cyprus, Barkay suggested the pyre found under the tumulus dug by Amiran was not connected to polytheistic cults. Instead, he hypothesized, the fire and the subsequent raising of the tumuli were linked to memorial ceremonies that the Bible says were held for deceased kings of Judah. The number of mounds roughly corresponds to the 21 biblical kings of Judah from David, sometime in the 11th-10th century B.C., to Zedekiah, whose reign ended when the Babylonians conquered Jerusalem and destroyed the First Temple in 586 B.C., Barkay argued.

According to the Bible, lighting a memorial pyre after the death of a king was done for monarchs who were considered just, so, for example, we are told that upon the death of King Asa, who reigned in the 9th century B.C., "they made a very great burning for him" (2 Chronicles 16:14), while in the case of the wicked King Jehoram "his people made no burning for him, like the burning for his fathers" (2 Chronicles 21:19).

In Barkay's reconstruction, the entire people of Judah would assemble for such ceremonies, which is why they were held outside the city. After the fire burnt out, participants would pile up stones and dirt to cover up the place of burning and erect a large memorial mound in honor of the king.

The problem with this theory is that if we exclude Albright's questionable dating, all the mounds that have been investigated so far go back to a very specific period: the very end of the 8th century B.C. and mainly the 7th century B.C., notes Tel Aviv University's Israel Finkelstein, one the country's most prominent biblical archaeologists. That means the mounds could not be memorials for biblical monarchs who reigned from the 11th-10th centuries B.C. onwards.

Judah's Chianti region

As with most archaeological research in the Holy Land nowadays, more recent interpretations of the mystery mounds have veered away from trying to find a direct connection between a find and a biblical passage. Instead, experts are now more interested in linking these sites to their historical context and archaeological discoveries that have emerged alongside them.

Pretty much every dig in the immediate surroundings of the tumuli has unearthed finds that can be related to agricultural production and administration. These discoveries include mainly large wine presses dug into the bedrock and dozens of jar handles bearing seal impressions and lettering in ancient Hebrew. Most bear the inscription "LMLK," which means "belonging to the king," and these seals were a hallmark of the Kingdom of Judah's administration in the late 8th and early 7th centuries B.C.E.The tumuli could therefore be seen as part of agricultural estates that arose from the increased population and prosperity of the Kingdom of Judah at end of the 8th century B.C., following the destruction of the northern Kingdom of Israel by the Assyrians and the flood of refugees that reached Jerusalem.

The ubiquitous wine presses suggest that, during this period, the area southwest of Jerusalem became a small wine country, argue Tel Aviv University's Raphael Greenberg and IAA archaeologist Gilad Cinnamon, who have excavated several of these installations around one of the largest tumuli, now located in the neighborhood of Ir Ganim.

As for the tumuli that seem so closely connected to wine production, Greenberg tells Haaretz that in an early stage they may have been stone enclosures used for storage purposes. They were later raised either to serve as communication points between the various estates or even just as symbolic markers setting the borders of this mini-Chianti region of Judah, he says.

Another interpretation, suggested by Baruch, the IAA's Jerusalem archaeologist, is that the tumuli mark these agricultural estates as belonging to a specific group or elite. This is based on the unique features of these sites and the fact that they continued to be in use for centuries after the end of the First Temple period and into the Second Temple period, irrespective of political developments.

"These areas may have served to produce wine, oil or other products that had to be made according to certain regulations, possibly by a specific guild or a branch of the Cohanim," the priests that served in the Temple in Jerusalem, Baruch says.

Taxes for the king

Yet other archaeologists, like Finkelstein, connect the mounds and their surrounding estates to the administrative center and palace that has been found nearby at Ramat Rachel, another key ancient site south of the Old City of Jerusalem. This royal complex is believed to have served as a storage and collection facility for taxes coming from across Judah starting from the end of the 8th century B.C. onwards.

This would mean that the fruits of the labor done around the tumuli were destined to become tribute for a centralized entity, either the Judahite monarchy or even the Assyrian Empire, which controlled the Levant at the time. At the end of the 8th century B.C., during Hezekiah's reign, Jerusalem was brought under the sphere of influence of the Assyrians, who had already destroyed the neighboring Kingdom of Israel and conquered its capital, Samaria, in 722 B.C. This process culminated in 701 B.C., when the Assyrian king Sennacherib invaded Judah and besieged Jerusalem.

The city did not fall, but Judah became a vassal of Assyria, and from then onward, excepting brief periods of autonomy, it would remain subjugated to a series of successive empires. The Assyrians would give way to the Egyptians, the Babylonians, the Persians, the Hellenistic kingdoms, the Romans and so on.

Given the historical context at the turn of the 8th century B.C., it is possible that the mounds were raised by the Assyrian conquerors or the local vassal kings as observation posts or simply as symbols of control over these key production and administrative sites.

Assyria is here

If the mystery mounds of Jerusalem are the mark of monarchic or even imperial power, nowhere should this be more evident than at the tumulus that was recently the focus of a three-year dig by the Israel Antiquities Authority in Arnona, near the new U.S. Embassy in Jerusalem. This is the largest of the mounds, reaching 20 meters in height and covering an area of 7 dunams (7,000 square meters). Raising it would have required the equivalent of hundreds of modern trucks carrying stones and soil from the surrounding fields.

Around it, archaeologists uncovered the now familiar coupling of wine presses and dozens of stamped jar handles mainly from the 8th-7th century B.C., which indicates that this too was a "center for collecting, producing and distributing agricultural produce," says Neria Sapir, the IAA archaeologist who led the dig.

Why this administrative center was covered by a huge mound of stones, sometime in the early 7th century B.C. remains unclear, but it may have been in connection with the recent Assyrian conquest. The hill on which the mound lies is a key strategic location that dominates the approach to Jerusalem from the south and east, Sapir notes.

"Whoever built this wanted to see and be seen, to project strength, especially to people who came from the countryside," Sapir says. "They wanted to show: 'I am here.'"

Sapir and colleagues also uncovered a confusing succession of structures that were built below and on top of this tumulus, in some cases within a span of a few decades. In short, it seems that the enormous heap buried a previously existing building, which is where most of the oldest seal impressions were found. Then, shortly after the mound was raised, someone dug a space within the tumulus to reach bedrock and built a new construction, made with massive ashlar stone blocks.

Here too the archaeologists found seal impressions indicating that the administrative activity resumed and continued until the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586 B.C.

Even more puzzling, later buildings were added atop this construction, ensconced in the mound of stones, after the return from the Babylonian exile, and the site continued to be settled through the Persian, Hellenistic and Roman periods.

"This is not the most comfortable place in the world: there is no water, these small flint stones are hard to walk on and radiate strong heat in the summer," Sapir tells Haaretz during a tour of the site. "And yet people kept coming back to this mound for centuries. It's very weird."

One possible explanation is that the site had some religious importance for the Judahite residents. The archeologists did find some clay figurines connected to polytheistic beliefs -- but these are commonly associated with domestic rituals and are found in many digs from the First Temple period, Sapir notes. It seems more likely that this was a case of one-upmanship between successive occupiers of the site, whether foreign invaders or local rulers, each one attempting to reclaim this strategic location, he says.

Ultimately, we still don't know if the tumuli of southwest Jerusalem were symbols of a conquering power, agricultural landmarks, places of worship or something else entirely. Perhaps, notes the IAA's Baruch, we shouldn't even be looking for a single, one-size-fits-all explanation.

"Maybe they are not a single phenomenon and we need to look at each one individually," he says. For now, the mounds continue to guard many of their secrets, but there are several archaeologists, including some of those interviewed for this story, who vow to continue digging until they solve this very peculiar puzzle.

or register to post a comment.