However, the guests Laursen invited to the Zoom call were notable: Sarah Graff, an associate curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City; and Sean Burrus, the Andrew W. Mellon postdoctoral curatorial fellow at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

While Seven Days listened in, Laursen's students presented to the two art historians their semester-long project: a website examining one of Middlebury College's first art acquisitions, which is a carved stone panel nearly 3,000 years old. The detailed relief, depicting a muscular, winged man with an impressive beard, is one of hundreds that once adorned the interior walls of the Northwest Palace, built by the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (who reigned from 883 to 859 BC), in Nimrud (near present-day Mosul, Iraq).

Graff and Burrus' institutions have some of those panels, too. In fact, when the British archaeologist Sir Austen Henry Layard published the results of his excavations of the palace in the 1840s, collectors and institutions around the world clamored to acquire panels for themselves.

The British Museum snagged enough to fill a couple of enormous rooms. Others were sold to excited Christian missionaries working nearby who believed they verified the Bible, which names Assyrian kings and places such as Nimrud (aka Nimrod). Middlebury got its panel from one of those missionaries: Alum Reverend Wilson Farnsworth, then preaching in Turkey, donated it to the college in about 1854.

Similar stories account for the presence of Northwest Palace artifacts in some two dozen institutions in the northeastern U.S. -- including a panel very similar to Middlebury's at the University of Vermont's Fleming Museum of Art in Burlington. (Curator Andrea Rosen also participated in the Zoom call.)

Middlebury College Museum of Art)

Middlebury College Museum of Art)

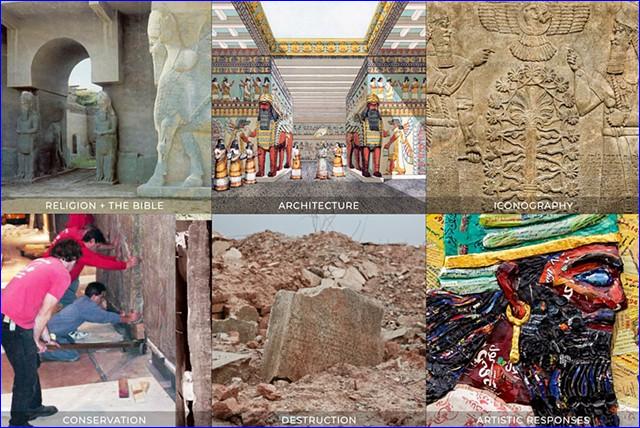

All these facts and many more are detailed on the visually appealing site the students made, which is titled NW x NE: The Assyrian Relief in the Middlebury College Museum of Art. Using ArcGIS StoryMaps, ThingLink, Sketchfab and other digital platforms, the site lays out a nonhierarchical grid of nine clickable panels dedicated to subjects such as Neo-Assyrian history, the palace's architecture, Assyrian iconography and conservation techniques.

The goal was to make the website as accessible as possible, Laursen later noted during a phone call. "We wanted it to reach any museumgoer -- little kids, retired professors, everyone," she said.

In that spirit, students condensed their extensive research into textual passages of 150 words or fewer -- similar to museum wall texts -- and composed them at an eighth-grade reading level. (For instance, apotropaic symbols are rephrased as "motifs to ward off evil.") They also assembled a glossary of terms that visitors might need to google and embedded each passage with a variety of videos, images, maps and visual backgrounds.

Graff and Burrus interjected commentary and critique during the Zoom session.

"I really appreciate how thoughtful you've been about thinking about your audience," said Graff, an Ancient Near East art specialist.

Burrus, a scholar of the Ancient Mediterranean art and archaeology, asked why the students had used WordPress rather than Squarespace to create the site. Senior Tenzin Dorjee, the site's webmaster, explained that it was because the platform was free, adding that they also didn't have to buy the domain.

Graff approved, commenting on "how important it is to use free and accessible technology on collaborative projects."

NW x NE was inspired by an initiative by Graff and Burrus to gather representatives from the palace-relief-owning institutions of the Northeast. Because it's impractical to reunite the panels physically -- each weighs about a ton -- the two art historians led a workshop at Bowdoin last May to brainstorm other modes of collaboration.

Representatives from more than 10 institutions attended, including Laursen, who is also curator of Asian art at the Middlebury College Museum of Art, and Fleming collections and exhibitions manager Margaret Tamulonis.

Laursen, who is about to begin a new job as associate curator of Chinese art at the Harvard Art Museums, said that workshop attendees discussed creating a digital exhibition about the palace. The group has continued to meet occasionally over a Slack channel. Meanwhile, Laursen thought of making the project the experimental subject of her digital methodologies course.

She added that many digital resources and reconstructions of the palace exist on the web already, including some "relics from the 2000s." Rather than reinvent the wheel, her students include one animated recreation of the king's private suite, produced by a private company called Learning Site, on their website. They also discuss reasons for the unreliability of any hypothetical reproduction of the palace.

Among the students' original contributions are two highly useful, interactive maps. One is a floor plan that allows visitors to click on a room in the palace and find where in the Northeast its original panels now reside, as well as an image, title, accession number and link to the object's online record.

The other is a map of the world pinpointing where all of the palace's panels and other artifacts are held. Graff called both "a really good step forward over the existing ways of mapping."

The Met curator also approved of the students' decision to dedicate one of the website's nine subjects to the role religion played in their dispersal.

"It's extremely puzzling and strange, this whole Biblical connection," she mused. "How sincere do you think this interest in the Bible was? Or was it about trophy hunting?"

Samantha Horton, a senior and the project's text editor, replied, "Trophy hunting was definitely part of it. It was about the idea that Christianity triumphed over this [Assyrian] religion."

Senior Allie Izzard, who compiled the glossary, added that the religious ramifications of the 19th-century dig mostly interested Americans. "British accounts were more about the swashbuckling aspects," she pointed out.

Either way, said Tamulonis about the Fleming's panel, the pillaged reliefs are ideal for jumpstarting discussions about the often "tortured provenance" of museum holdings.

The Middlelbury students' website also addresses the difficult issue of repatriation. But the idea of returning the panels to Iraq is complicated not just by their unwieldy weight but by recent events. In 2015, ISIS destroyed the remains of the palace with bulldozers and explosives and either broke the remaining treasures or sold them on the black market. (One important relief panel owned by a seminary in Virginia since 1860 garnered $30.1 million in an auction at Christie's in New York City on October 31, 2018, so the potential gains for the militants are significant if they can find buyers.)

Eventually, visitors will once again be able to view Middlebury's Assyrian relief panel next to the museum's reception desk, or the Fleming's cemented into a wall in the Marble Court, and examine these expertly carved visions of supernatural beings in person. Until then, anyone anywhere can learn all about them at the NW x NE website.

or register to post a comment.