Enid Tsui)

Enid Tsui)

The exhibition has made Hong Kong its first stop (at the Museum of History) before moving on to Spain, and is another example of how the British Museum is a pioneer in presenting history through objects in engaging ways.

It offers more than just an excellent history lesson on the Assyrians, the Babylonians and the Achaemenids, for ancient Nineveh is present-day Mosul. What God or successive invaders spared, so-called Islamic State's militants have done their utmost to destroy.

When the immediate is hell, a preoccupation with the frivolous luxuries of a bygone age may seem oddly facetious, a blinkered historic focus detached from heinous sufferings on the ground. But this understated show about the sophistication of design and craftsmanship from thousands of years ago is actually an evocative reflection on why we grieve over the wanton destruction of cultural relics in Nimrud, Mosul, Palmyra and Bamiyan. These were our shared heritage.

"This is a follow-up to the fabulous Mesopotamia exhibition that we took to Hong Kong in 2013," says Alexandra Fletcher, assistant keeper, Middle East department at the British Museum. "We hope that the theme of luxury will connect with different people around the world because it shows that people used to like the same things as we do, and had the same desires and wants that we do now."

There is a section for each successive empire that dominated the Levant region from 900-300BC. The first were the Assyrians, who spread from northern Iraq to rule territories all the way from the Persian Gulf to Egypt.

Enid Tsui)

Enid Tsui)

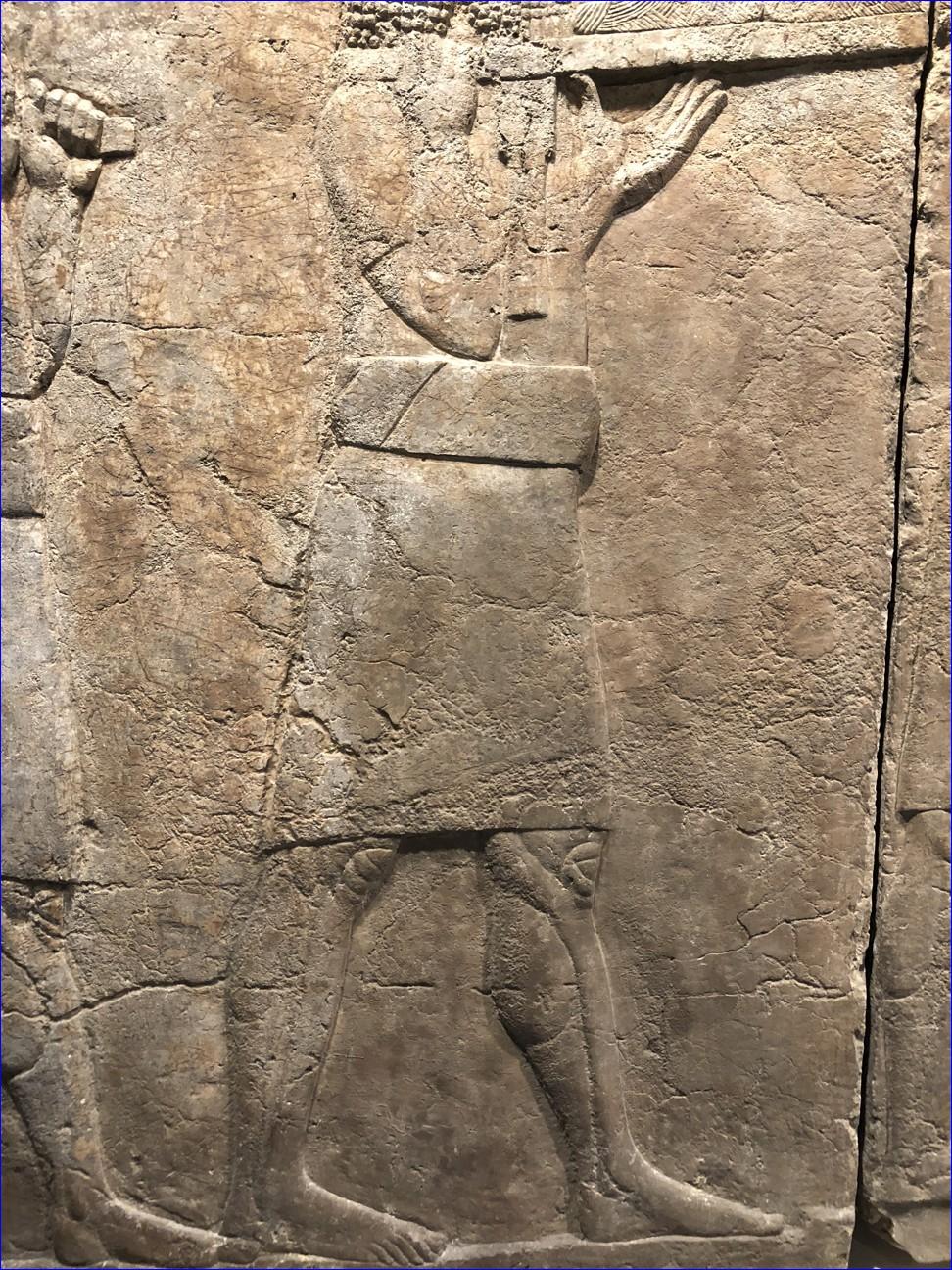

Their kings -- portrayed in signature braided hair and long, clipped beards on stone reliefs -- showed off power and wealth from palaces in Nimrud and Nineveh, decorated with stone and ivory plaques.

One of the exhibits is an ivory plaque from Nimrud with a sphinx resting one paw on a papyrus plant. It is accompanied by a touch screen that allows visitors to see the object from different angles and tap on annotated details.

There are also original stone reliefs showing scenes from the pleasure gardens at Nineveh, which were irrigated by a sophisticated network of canals full of fish, and filled with fruit trees and grazing animals.

One of the most remarkable of the 210 exhibits is a clay cylinder that the Assyrian King Sennacherib buried in the foundations of his palace at Nineveh. The cuneiform text states that construction of "The Palace Without a Rival" took several years, and prisoners of war were used as labour.

This was created around the same time as the famous "Flood Tablet" at the British Museum -- the Assyrian clay tablet that tells of the flood story in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Enid Tsui)

Enid Tsui)

After the Assyrians came the Babylonians with their own fabled gardens. Greek historian Herodotus wrote about how much they loved dressing up, and the exhibition shows golden earrings shaped like flowers, finely carved make-up palettes used by men and women, and elaborate, animal-shaped fittings made of gold that were sewn on ceremonial garments.

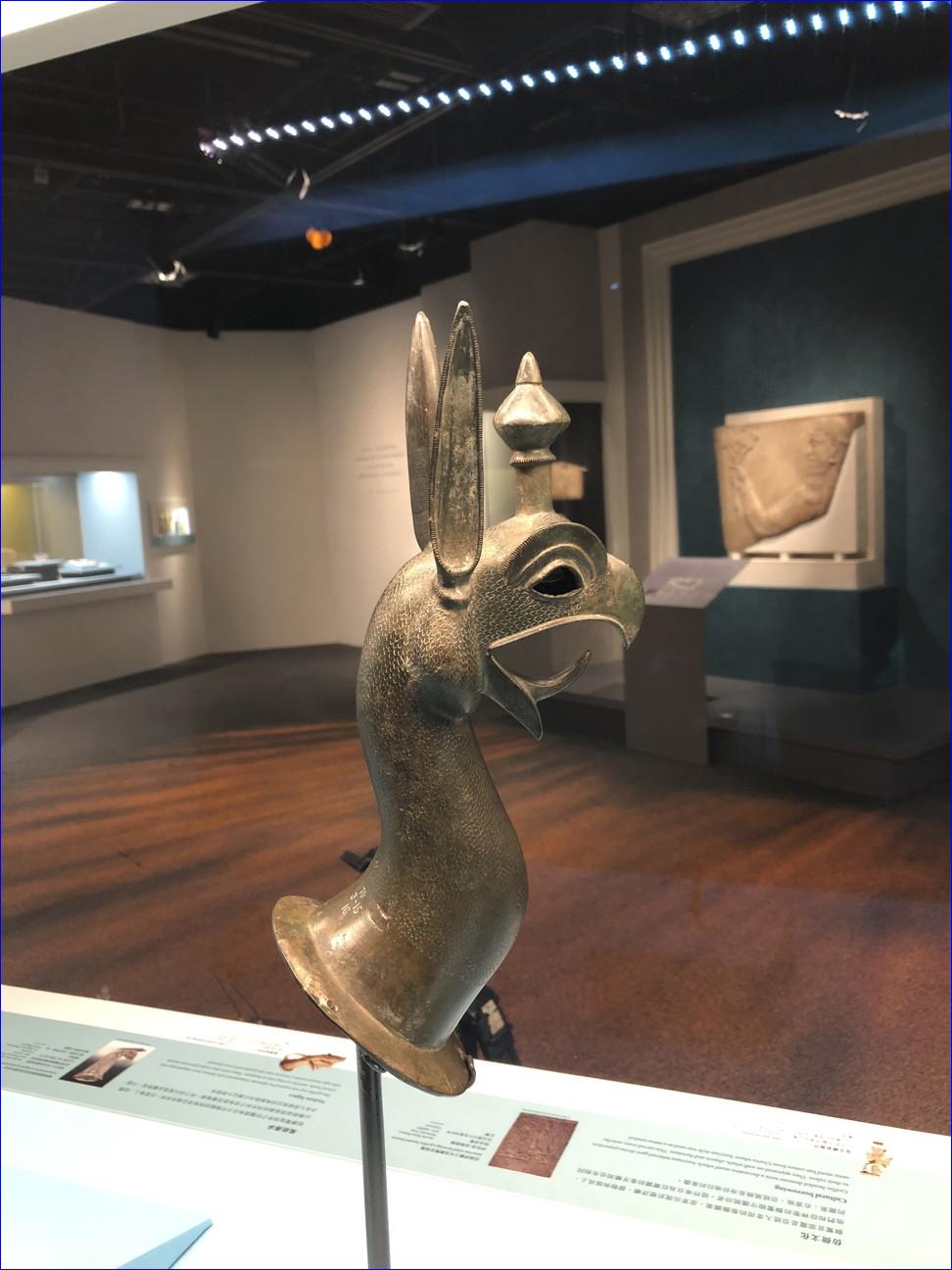

The Achaemenids, who rose up after the Babylonians, were the great goldsmiths. One of the finest exhibits in the show is an Achaemenid flask in the shape of a fish that was hammered from a single sheet of gold. They also loved their wine, as shown by a horn-shaped wine cup made of silver and gold that holds up to two bottles of wine.

There are also sections on the Phoenicians and on Alexander the Great, and the exhibition is further enhanced by animations provided by the Museum of History that bring some of the stone reliefs to life.

Enid Tsui)

Enid Tsui)

There is a dark side to all this glitter, however. "The Nineveh stone relief shows the Assyrian army burning and looting," Fletcher says. "They took away bronze vessels like the ones we are showing here. Looting is an uncomfortable side of luxury."

There are uncomfortable parallels, too, with how these exhibits ended up in Britain. The artefacts from Nimrod and Nineveh were found in the 19th century by the British adventurer and politician Austen Henry Layard and his followers, who competed against French archaeologists to find lost treasures and sent the best pieces to the British Museum.

Enid Tsui)

Enid Tsui)

Cultural patrimony is a long-standing debate. But given the instability of the Middle East and the devastation of Nimrud -- and, more recently, Mosul -- the focus now is on preservation rather than repatriation, for there is no doubt the artefacts are safer in London or Paris.

"We are supporting a training scheme for our colleagues in Iraq heritage institutions who are trying to rebuild their cultural infrastructure," Fletcher says. "The British Museum has a global collection and we share it with the world by making loans like the Hong Kong exhibition."

or register to post a comment.