The Trustees of the British Museum)

The Trustees of the British Museum)

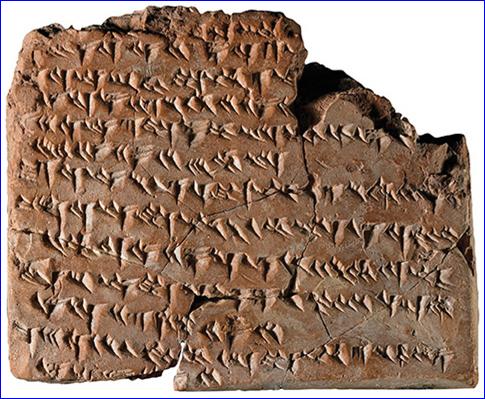

First developed around 3200 B.C. by Sumerian scribes in the ancient city-state of Uruk, in present-day Iraq, as a means of recording transactions, cuneiform writing was created by using a reed stylus to make wedge-shaped indentations in clay tablets. Later scribes would chisel cuneiform into a variety of stone objects as well. Different combinations of these marks represented syllables, which could in turn be put together to form words. Cuneiform as a robust writing tradition endured 3,000 years. The script--not itself a language--was used by scribes of multiple cultures over that time to write a number of languages other than Sumerian, most notably Akkadian, a Semitic language that was the lingua franca of the Assyrian and Babylonian Empires.

After cuneiform was replaced by alphabetic writing sometime after the first century A.D., the hundreds of thousands of clay tablets and other inscribed objects went unread for nearly 2,000 years. It wasn't until the early nineteenth century, when archaeologists first began to excavate the tablets, that scholars could begin to attempt to understand these texts. One important early key to deciphering the script proved to be the discovery of a kind of cuneiform Rosetta Stone, a circa 500 B.C. trilingual inscription at the site of Bisitun Pass in Iran. Written in Persian, Akkadian, and an Iranian language known as Elamite, it recorded the feats of the Achaemenid king Darius the Great (r. 521--486 B.C.). By deciphering repetitive words such as "Darius" and "king" in Persian, scholars were able to slowly piece together how cuneiform worked. Called Assyriologists, these specialists were eventually able to translate different languages written in cuneiform across many eras, though some early versions of the script remain undeciphered.

Today, the ability to read cuneiform is the key to understanding all manner of cultural activities in the ancient Near East--from determining what was known of the cosmos and its workings, to the august lives of Assyrian kings, to the secrets of making a Babylonian stew. Of the estimated half-million cuneiform objects that have been excavated, many have yet to be catalogued and translated. Here, a few fine and varied examples of some of the most interesting ones that have been.

Letters

Among the thousands of Mesopotamian tablets containing both official and personal letters, one example stands out as the first recorded customer complaint and evidence of a business relationship gone very sour. Nearly 4,000 years ago, a man named Nanni expressed his extreme displeasure to the merchant Ea-nasir about a recent copper shipment:

When you came, you said to me as follows: "I will give Gimil-Sin (when he comes) fine quality copper ingots." You left then but you did not do what you promised me. You put ingots that were not good before my messenger (Sit-Sin) and said: "If you want to take them, take them; if you do not want to take them, go away!" What do you take me for, that you treat somebody like me with such contempt....Take cognizance that (from now on) I will not accept here any copper from you that is not of fine quality. I shall (from now on) select and take the ingots individually in my own yard, and I shall exercise against you my right of rejection because you have treated me with contempt.

Recipes

The earliest known recipes, by many centuries, are found on three tablets dating to the Old Babylonian period. Though seemingly simple, their minimal instructions could only have been followed by experienced chefs working for the highest echelons of society. This particular tablet features 25 recipes for stews and soups, both meat and vegetarian, including some directions--though no measurements or cooking times--for an amursanu-pigeon stew:

- Split the pigeon in half--add other meat.

- Prepare the water, add fat and salt to taste;

- Breadcrumbs, onion, samidu, leeks, and garlic

- (first soak the herbs in milk).

- When it is cooked, it is ready to serve.

With the exception of amursanu, which is probably a type of pigeon, and samidu, an unknown spice, the ingredients are certainly recognizable. But the dish would, in fact, be impossible to replicate, says Benjamin Foster, curator of the Yale Babylonian Collection. "People often think that because they can cook Arab or Persian food that they can make this stuff, but they don't know how much regional cooking was changed by the Muslim conquests. If you cook these up using modern Near Eastern ingredients, it is pure fantasy--but often delicious."

Laws

The best known and most influential of the Mesopotamian law codes was that of King Hammurabi of Babylonia (r. 1792--1750 B.C.). Featuring nearly 300 provisions covering topics ranging from marriage and inheritance to theft and murder, it is the most comprehensive of these codes. While it famously includes retributive, eye-for-an-eye clauses, it also takes on more complex scenarios, imposing harsh punishments for accusation without proof and for errors made by judges.

The code appears written in intentionally archaic cuneiform on a towering seven-and-a-half-foot-tall diorite stela that was recovered from Susa, in present-day Iran, where it was taken after being stolen in the twelfth century B.C. Featuring a relief of Hammurabi receiving divine sanction from the sun-god Shamash in its upper portion, this stela and others like it would have been publicly displayed during Hammurabi's reign and long after. "The code was certainly set up in in city squares, in temple courtyards, in public places--where it was seen by populations," says Martha Roth, an Assyriologist at the University of Chicago. It was also used in the training of scribes for at least 1,000 years after its composition, and several manuscripts of it were found in King Ashurbanipal's (r. 668--627 B.C.) seventh-century B.C. library at Nineveh, in present-day Iraq.

The precise legal function of Hammurabi's code is unclear, as there are few references to it in legal records from his era. However, says Roth, these records do suggest that "the provisions as outlined in Hammurabi map onto the daily reality in a fairly close way." The code was also clearly intended to establish Hammurabi as the guarantor of justice for his people. "In order that the mighty not wrong the weak, to provide just ways for the waif and the widow," reads its epilogue, "I have inscribed my precious pronouncements upon my stela."

This trope of the king as protector of the downtrodden appears regularly in Mesopotamian inscriptions, but the earliest known example is found on several cone tablets known as the reforms of Urukagina (r. ca. 2350 B.C.), a king of the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present-day Iraq. According to the inscriptions, the king addressed a number of social inequities, including reducing the power of greedy temple overseers and abusive foremen. "There's a consciousness about reform in it that is unique until now," says Roth, "and in history it comes about here for the first time."

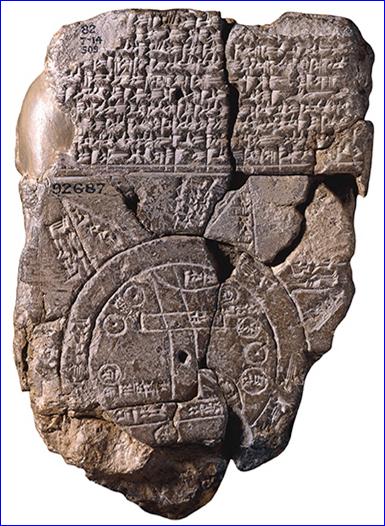

Maps

The Trustees of the British Museum)

The Trustees of the British Museum)

According to Wayne Horowitz of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the tablet "reflects a general interest with distant areas during the first half of the first millennium, when the Assyrian and Babylonian Empires reached their greatest extents."

Medicine

In the ancient Near East, illness was as much a spiritual affliction as a physical one. Demons and ghosts played large roles in diagnosis and treatment, but that's not to say that the practice of medicine wasn't codified. One collection of cuneiform texts lists hundreds of medically active substances. And the Late Babylonian diagnostic manual called Sakikku, or "All Diseases," reveals the careful diagnostic observation of ashipu, or doctor-scholars. The manual, which dates to around the sixth century B.C., consists of 40 tablets, including a treatise on the diagnosis of epilepsy, called miqtu, or "the falling disease." The writer explains the subtleties of the neurological disease's presentation in great detail, provides basic prognoses, and ascribes different kinds of seizures to particular malevolent spirits. "[If the epilepsy] demon falls upon him and on a given day he seven times pursues him--[he has been touched by the] hand of the departed spirit of a murderer. He will die."

Religion

In November 1872, a self-taught Assyriologist named George Smith working as an assistant at the British Museum happened upon a fragment of a tablet that would soon become the most famous cuneiform text in the world. One of thousands excavated decades earlier at Nineveh, in present-day Iraq, the tablet told a story eerily similar to that of Noah in the Old Testament. In it, the gods resolve to destroy the world and all life with a great flood, but one of the chief gods warns one man in time to prevent the extinction of all living things: "Demolish the house, build a boat!" the god urges. "Abandon riches and seek survival! Spurn property and save life! Put on board the boat the seed of all living creatures!"

The man, his family, and assorted animals wait out the flood in the boat while all other living things perish. Smith presented his translation several weeks later at the Society of Biblical Archaeology to a packed audience that included the prime minister, the archbishop of Canterbury, and many members of the press. "When Smith announced that one of these unappetizing-looking tablets from the barbaric, strange world of the Middle East contained a parallel text to Holy Writ, people were astonished," says Irving Finkel, a cuneiform expert at the British Museum.

The tablet deciphered by Smith turned out to be the 11th part of the 12-tablet Epic of Gilgamesh and had belonged to the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (r. 668--627 B.C.), who aspired to gather all known cuneiform writings. Since Smith's discovery, more than a dozen cuneiform tablets containing some portion of the flood myth have been identified, the earliest of which predate the earliest known versions of the biblical flood text by a thousand years.

Kings

Royal inscriptions are among the most important sources of ancient Near Eastern history. One of the most intriguing examples is found on the statue of King Idrimi, who ruled Alalakh, a city in present-day Turkey, in the fifteenth century B.C. A lengthy cuneiform inscription sprawls across the statue, spinning a first-person tale of exile, triumph, and redemption.

"In Aleppo, the house of my father," it begins, "a bad thing occurred, so we fled to the Emarites, my mother's kin." Idrimi, a younger son unwilling to play a diminished role, decamps for Canaan, where he finds countrymen who recognize his royal lineage. With their help, he wins over his home city and is proclaimed its rightful ruler by the king of Mitanni, the major regional power. Idrimi then repairs Alalakh's toppled city wall, conquers more cities, builds a palace, cares for his people, and performs the necessary prayers and sacrifices.

The portion of the inscription that covers Idrimi's reign is very similar to inscriptions left behind by kings from across the ancient Near East, from Hammurabi of Babylonia (r. 1792--1750 B.C.) to Ashurnasirpal II of Assyria (r. 883--859 B.C.). "The things Idrimi does once he becomes king are the things that Near Eastern kings conventionally claimed to have done in their inscriptions," says Jacob Lauinger, an Assyriologist at Johns Hopkins University. However, Lauinger adds, the portion covering Idrimi's exile is more akin to the Old Testament stories of Joseph and David, both younger sons who reach great heights. Just as the inscription's narrative is a hybrid, so is its language. It is written in Akkadian cuneiform--as was only proper for a royal inscription at the time--but with clear Canaanite influences, such as the placement of verbs at the beginning of clauses.

Although the text reads as if written by Idrimi during his reign, a recent reanalysis of the statue's stratigraphy suggests it may actually have been written several decades later. As scholars continue to puzzle over this most unusual royal inscription, the wish expressed in its final lines has been fulfilled: "I wrote my service down on my tablet. May one regularly look upon them [the words] so that they [the words] may call blessings on me regularly."

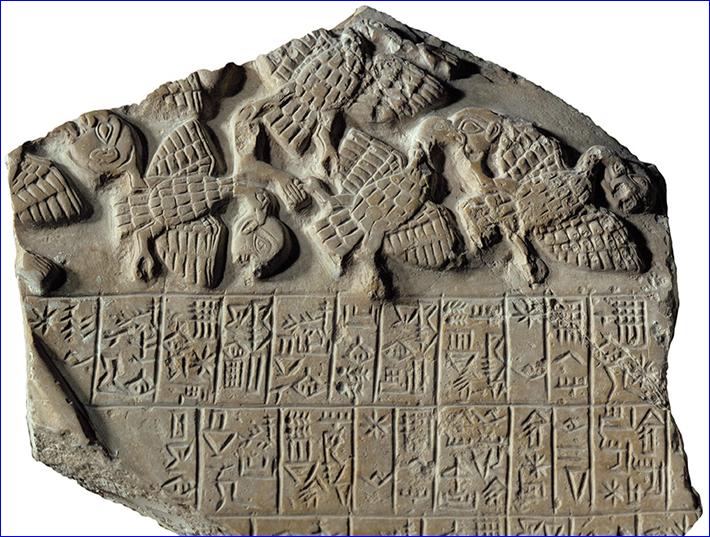

Warfare

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)

During this period, Sumer was a collection of city-states surrounded by agricultural land. As the city-states grew, so did the potential for border conflicts, such as one that raged for 200 years between Lagash and Umma, both in present-day Iraq. The Stela of the Vultures, which survives as seven fragments of what was once a six-foot slab of limestone, records Lagash's eventual victory. One side depicts the god Ningirsu, holding his enemies in a sack, while the other shows a series of scenes from the conflict. A cuneiform account by Lagash's leader, Eannatum, wraps around the stela: "Eannatum struck at Umma," it reads. "The bodies were soon 3,600 in number....I, Eannatum, like a fierce storm wind, I unleashed the tempest!"

The historical side depicts Eannatum leading a phalanx of soldiers trampling enemies underfoot, a victory parade, a funeral ceremony, and another, poorly preserved tableau--along with, at top, the image that gives the stela its name, a kettle of vultures consuming the heads of Umma soldiers. It is, in a way, a document both poetic and legal--it invokes the grace and power of Ningirsu, and stakes a claim to land won by force.

Lagash's primacy was short-lived. By the end of the period, Umma had plundered its rival and begun the consolidation of power that would result in the rise of the Akkadian Empire. The tradition of documenting battles in words and pictures continued, perhaps reaching a peak with the Assyrians in the seventh century B.C., when they carved elaborate battle reliefs in the North Palace of Nineveh in present-day Iraq, and documented the siege of Jerusalem on a series of octagonal clay prisms called Sennacherib's Annals.

Last Tablets

Though Akkadian as a spoken language in Mesopotamia died out toward the end of the first millennium B.C., cuneiform continued to be used by temple scribes and astrologers. Greek scholars are known to have flocked to Babylon during this time to learn astronomy, and excavated tablets inscribed in both Greek and Akkadian show that at least a few of these visiting astronomers even tried to master the art of writing cuneiform. But the end was near. The last known tablets that can be dated were written in the late first century A.D. Some scholars believe cuneiform ceased to be used around that time, but Assyriologist Markham Geller of the Free University of Berlin believes it endured for another two centuries. He points to classical sources that mention that Babylonian temples continued to thrive, and believes that they would have maintained scribes still capable of reading and writing cuneiform to ensure that rituals were properly performed. He also thinks cuneiform medical texts may have continued to be used to diagnose illnesses during this era.

But in the third century A.D., the neighboring Sassanian Empire, known to be hostile to foreign religions, seized Babylon. "They shut the temples down," says Geller, "and they sent everyone home." He believes it was only when the very last of these temple scribes died that the rich, 3,000-year-old cuneiform record finally fell silent.

or register to post a comment.