Trustees of the British Museum)

Trustees of the British Museum)

Commensality, the practice of eating together, reflects social relations and can at the same time open a view on the mechanisms of politics. In the stratified and hierarchic Neo-Assyrian society, a banquet could represent the moment in which the power of the central administration was made visible to the community. Food should, therefore, be examined within the complex symbolism of Neo-Assyrian propaganda.

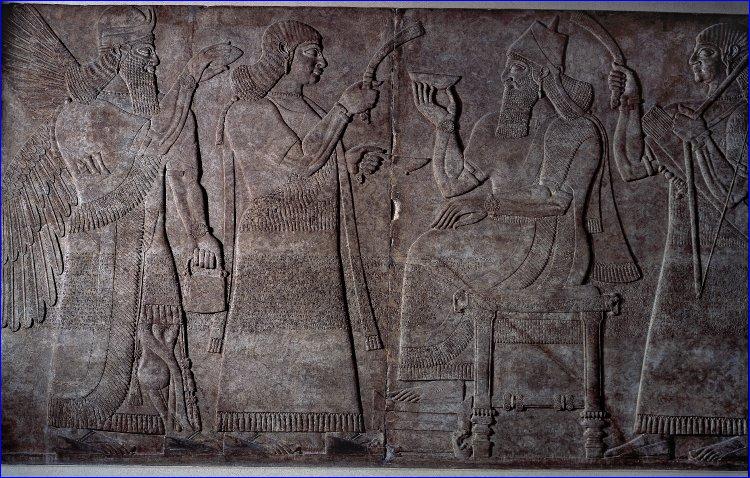

The Assyrian king was the main promoter of big feasts and special events, during which he played the role of leader and benefactor of his country. Food appears frequently in texts and images originating with the royal inner circle, in the guise of offerings made to the gods, tributes presented by vassal kings, rations distributed to officers or court personnel, and meals consumed in different circumstances.

The king's table was a preferred place for making important decisions concerning the empire, exchanging political information, publicly displaying the wealth of Assyria, and distributing surpluses accumulated during months of successful economic management. It was, moreover, an appropriate stage to exhibit both the immeasurable benevolence of the gods who provided lavish and exquisite food to the land, as well as the authority, strength, and managerial skills of the Assyrian king. But Mesopotamian banquets clearly were also nutritious, an aspect which was enhanced by the pleasures of tasty dishes, abundant drinks, good company, and various entertainments.

Near Eastern cooks used to combine flavours in a way that may appear quite unusual to us today, mixing for example garlic and sugar, and not paying attention to the categories of 'salty' and 'sweet'. They loved strong-tasting and spicy food and made large use of seasoning. They enjoyed quite a wide variety of foods and were able to take advantage of every natural element, to obtain ingredients for which they developed specific recipes.

Assyrian men liked the taste of grilled, toasted, burned, but also fermented and sour foodstuffs, and learnt how to conserve them for a long time by the use of additives. The overall perception from written sources and images is that Assyrians produced a high-quality, specialized, unique and complex culinary art.

The best-known source for a Neo-Assyrian royal feast is the so-called Banquet Stele. This peculiar document was set up to commemorate the inauguration of the North-West Palace at Kalhu (modern Nimrud), built on the instructions of the king Aššurnasirpal II (883-859 BCE). Mesopotamian royal residences were the physical arena for great public displays -- but at the same time, they were the settings for more private meetings, family reunions, and assemblies of the king with his most intimate friends. These occasions often saw their protagonists sitting at a dining table. Aššurnasirpal II, who decided to re-establish Kalhu as the centre of his empire and thus began a massive project of renovation in the city, left many accounts of his military deeds and building projects, but the inscription reporting the inauguration festivities of his capital city has no duplicates.

Despite the name that has been given to it by modern scholars, it is striking that the stele does not depict a banquet at all: it represents, instead, a list of edibles, very similar to many contemporary administrative records and accounts of foodstuffs. The ingredients, both solid and liquid, appear listed without indications on how they were afterwards mixed together or handled or cooked, to prepare finished courses. There are, moreover, no hints as to the physical space in which the banquet took place. Given the very high numbers of diners (almost 70,000!), it is likely that the whole city of Kalhu became the stage for the celebrations. The king must have been sitting with his family and the higher internal and foreign officials inside the new palace, while the citizens (men and women from every part of Assyria) must have been placed in other buildings, courtyards and every other open space available in the city. The 'geography' of the banquet, therefore, reflected the proximity of each individual to the king by his distance from the royal residence.

This unique document begins with the noblest and most expensive foodstuffs, especially meat. Tens of animal species are enumerated following a precise order: first domestic livestock (oxen and sheep), followed by game, birds, fish, small rodents and poultry. The enumeration of greens is even longer and more varied and includes cereals (the stele mentions 10,000 loaves of bread!), legumes, flowering plants, vegetables, fruits, spices and oil. As for beverages, beer and wine are included but water is not listed, probably because its presence on the table was considered obvious. Finally, the mention of hundreds of vessels containing milk is quite remarkable. Easily perishable, the use of milk in feasting was not widespread, while its by-products, especially cheese, were.

Gods are the first guests to be invited to the repast, although this was not intended for them: they had already received their meals inside their temples, before the beginning of the 'earthly' banquet. Among the human invitees, a hierarchy can be perceived. The most numerous group comes from "all the lands of the country", that is of Assyria. This particular number -- 47,074 people, to be precise -- is the only uneven one quoted on the stele. The numbers that follow are even and include 5,000 dignitaries and ambassadors of the small countries around Assyria, 16,000 people resident in Kalhu and 1,500 royal officers and functionaries active in the royal residence. In all, 69,574 people were hosted in the royal household for ten days of celebration.

The overall impression conveyed by the Banquet Stele is one of an exceptional exhibit of power and control. There is no other document that expresses so vividly and evidently the magnificence and richness of a state banquet in first millennium Assyria, as a tool for celebrating contemporaneously the unrivalled might of the king and the administrative organization under his control.

Stefania Ermidoro is a post-doctoral researcher at KU Leuven, Belgium.

References used and items for further reading:

Bottéro, J. (1995). Textes culinaires Mésopotamiens: Mesopotamian Culinary Texts (Mesopotamian Civilizations 6). Winona Lake.

Dietler, M.; Hayden, B. (eds.) (2001). Feasts: Archaeological and Ethnographic Perspectives on Food, Politics, and Power. Washington; London.

Ermidoro S. (2015). Commensality and Ceremonial Meals in the Neo-Assyrian Period (Antichistica 8. Studi Orientali 3). Venezia. http://virgo.unive.it/ecf-workflow/upload_pdf/Antichistica_8_DIGITALE.pdf

Pollock, S. 2012 (ed.), Between Feasts and Daily Meals: Towards an Archaeology of Commensal Spaces. Berlin. eTopoi. Journal for Ancient Studies, Special Volume 2. Exzellenzcluster 264 Topoi. https://www.topoi.org/publication/19015/

or register to post a comment.