And that danger is not just limited to ancient Iraqi buildings, sculptures and artefacts, but evidence of life, society and culture from across the Middle East -- Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Israel and Turkey -- and beyond to the eastern Mediterranean.

Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art is an ambitious exhibition that traces the rich interaction between the people across these lands around the first millennium BC. It is, according to the exhibition's curator, Joan Aruz, a unique approach.

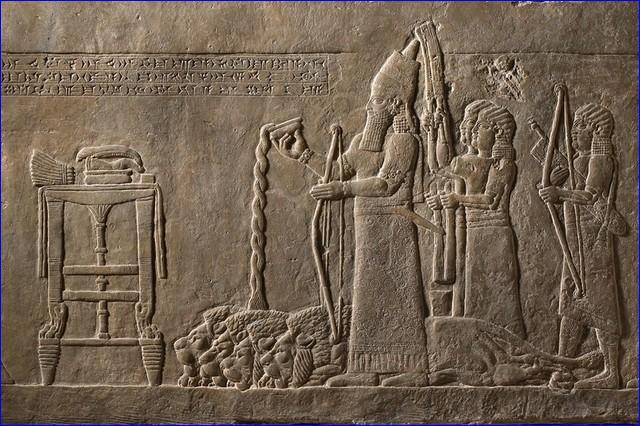

On display are wall reliefs, monumental sculptures, carvings in ivory, metalwork and jewellery -- 260 works of art on loan from 41 museums across the globe.

"We never see these cultures in contrast. Nobody's put this era together so that we can see the cross-currents of interaction and the magnificent flowering of the arts that took place as a result of this cross-fertilisation of cultures."

Assyria was originally one of many small states that existed in the Middle East in the second millennium BC. But the Assyrians embarked on an aggressive military expansion and at its peak in the 8th and 7th centuries BC, theirs was probably the largest empire the world had yet seen, spanning 1,600 kilometres westward from their base in modern-day Mosul as far as the Mediterranean.

"They developed a very strong army and they began to conquer their neighbours. In part it is because a lot of the other territorial states that kept them in check were destroyed and Egypt was no longer a big player so they were able to develop," says Aruz.

The Assyrians could be brutal and people who refused to pay tribute were attacked, cities were sacked and entire populations forcibly resettled.

One of the first works on display is a powerful example of Assyrian sculpture -- a statue of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II, who reigned from 883-859BC. Ashurnasirpal was known for mercilessly putting down rebellions and the inscription on the stone torso records his military campaigns in the west reaching as far as the "Great Sea" -- the Mediterranean.

But the exhibition paints a much broader sweep than mere war. Yes, it is a story of conflict and conquest but, also, commerce, global communication and artistic curiosity -- the flow of trade, commerce and ideas around the Near East and beyond.

Central to this are the Phoenicians -- expert seafarers who built ships that could carry large amounts of cargo and who, from their base on the Levantine coast, criss-crossed the Mediterranean acquiring the raw materials that their artisans turned into luxury goods.

"There were the people who were either conquered and then became vassals of the Assyrians and then there were people like the Phoenicians who paid tribute and were allowed to operate semi-independently. But they filled the Assyrian coffers in order to reach that status," says Aruz.

"They mastered the art of navigation where they could go across islands, island-hopping, to speed up travel, rather than always hugging the coast. They reached past the Strait of Gibraltar, which was the end of the known world at the time, called the Pillars of Hercules. They established a base at Carthage and went as far as Portugal and Spain and the Atlantic coast of Morocco, so they had a very great reach," says Aruz.

These maritime networks were exploited by the Assyrians. They did not have a navy, had little access to the sea and therefore relied on the Phoenicians to secure access to the riches of the West, especially silver from southern Iberia.

At archaeological sites throughout the Mediterranean, objects have been found with popular Middle Eastern motifs, such as griffins, human-headed birds and sphinxes. These were made in the Middle East and could have found their way west through trade but they were also made by local artisans who incorporated this imagery into their own work. These imported and locally produced artefacts were also found in the tombs of the wealthy in Greece and Italy and included monumental cauldrons with animal-head attachments on the rim.

"The Phoenicians contributed in the sending of technology and expert craftsmen. They stimulated an orientalising era and the Assyrians absorbed these influences.

"The Phoenicians also transmitted the alphabet to the West. This was the greatest gift that they gave, which changed the course of writing and literature," says Aruz.

However, not even these famed maritime traders were immune from the Assyrians' thirst for control. Eventually they were conquered and restrictions placed on their business, particularly in their prized trade in cedarwood from Lebanon.

"But before that there were periods where they were left quite independent. They were merchants, traders, explorers, navigators, shipbuilders -- the Assyrians benefited from that."

But more war and upheaval were to follow. Towards the end of the 7th century BC, the Babylonians began to push back the Assyrians, eventually destroying the capital, Nineveh. Babylon was rebuilt on a grand scale and the exhibition shows its glorious rise, with a model of the famed Ishtar Gate and Processional Way, along with several actual reliefs from these monuments.

For a time, Babylon was a global nexus of culture, economy and religion. But it would not last long, just 100 years. Ahead was classical Greece and another great empire, the Persians, who came from the east to sweep it all away.

"The show begins with the arts of the Assyrian worlds. Then we go to the Phoenician homeland and also to Cyprus, colonised by the Phoenicians. Then we go to the Mediterranean and trace a route from Samos to Rhodes to Crete to the sanctuaries of Delphi and Olympia.

"We also have objects from Carthage and Tunisia and then we examine a Phoenician shipwreck that went down off the coast of southern Spain," says Aruz.

"So people travel. It is like The Odyssey. You are on a voyage of discovery."

Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age runs until January 4. Visit www.metmuseum.org for more information.

or register to post a comment.