Almost 3,000 years ago, the rulers and wealthy elite of the powerful Assyrian empire adorned their chairs, stools and other furniture--even their chariots along with horses' halters and blinkers--with exquisitely decorated pieces of elephant ivory produced mostly by expert Levantine craftsmen.

With the collapse of the empire in 612 BC, and the sacking and burning of royal palaces by conquering Babylonians and Medes, the ivory disappeared under the rubble--not to be seen again until archaeologists began excavating it in the mid-19th century.

The British Museum in London has recently saved for the nation a horde of the so-called Nimrud ivories--1,000 intact pieces, 5,000 fragments--after a public fund-raising campaign that netted £1.17 million. That was about a third of the value of the ivories, and another third of the collection was donated by the British Institute for the Study of Iraq. The remaining third is expected to be returned to Iraq.

The Nimrud ivories, named for the Assyrian capital where they were found in modern Iraq, are regarded by the museum as probably the most important British archeological find in the Middle East.

"Every aspect of the decoration of the ivories reveals just wonderful craftsmanship," Nigel Tallis, the museum's Middle East curator, told about 300 museum members in a lecture. "Even now a full analysis of the significance of the collection has barely begun. Its acquisition by the museum is a cause for celebration."

The first group of ivories, dating from the 9th and 8th centuries BC, was excavated by the archaeologist Austin Henry Layard in 1845 at Nimrud, just south of Mosul on the Tigris River. They came from the ruins of the palace of Shalmaneser III, who ruled from 859 to 824 B.C., and more came to light a few years later.

But it was not until 1949-63 that the next discoveries were made by a team led by the celebrated archeologist Max Mallowan, second husband of the crime novelist Agatha Christie. Many of the ivories had been thrown into wells after having been stripped of colored glass, semi-precious stones and gold leaf that adorned them. A few of the ivories retain fragments of glass inlays.

Christie herself went on the expedition and helped photograph and preserve many of the ivories. In her autobiography, she wrote that she cleaned them using a fine knitting needle, an orange stick and a pot of face cream. Mallowan also credited her with coming up with the idea of placing newly excavated pieces under damp towels to prevent cracking.

"Oh what a beautiful spot it was," the novelist wrote. "The Tigris just a mile away, and on the great mound of the Acropolis, big stone Assyrian heads poked out of the soil. In one place there was the enormous wing of a great genie."

It was this aspect of the story--a woman writing novels in the morning and helping recover buried treasure in the afternoon--that caught the imagination of the British public and probably accounted in part for the enthusiastic response to the museum's fund appeal.

Tallis is particularly intrigued by the craftsmanship that went into incising and decorating some tiny pieces of ivory, no more than 1.5 or 2 centimeters (0.6 or 0.8 of an inch) high. The craftsmen, he said, must have been very young and probably were unable to go on working after their eyesight became damaged by the delicate task of incising such minute pieces.

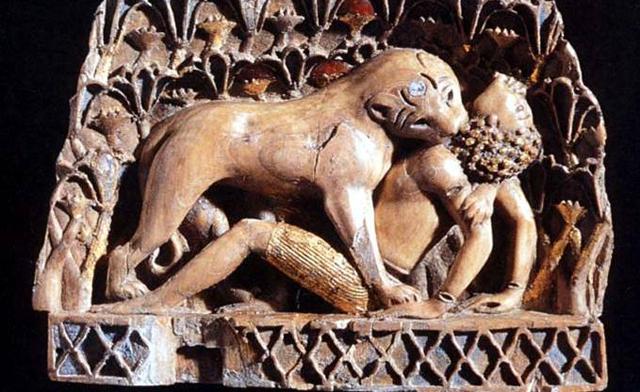

The ivories depict bulls, lions, griffins, wild goats, serpents, fighting heroes, flowers and geometric designs. A few were decorated in Assyria, but most came from the Levant and are believed to have been brought to Nimrud as war booty or imported as luxury goods. There is also an Egyptian influence in some of the pieces, for example those representing the sphinx and those using imitation hieroglyphs that have no apparent meaning.

The ivory came from Syrian elephants, endemic in the Middle East in ancient times, but by the 8th century BC they had been hunted to extinction and later ivory may have been imported from India.

The collection was long ago divided between Iraq and Britain, and those that were assigned to Britain were put in storage at the British Museum but not displayed. Many of the ivories at the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad were looted or damaged after the American-led invasion in 2003, when US troops failed to secure the museum's contents. Some were also stored in a Baghdad bank vault but were damaged by water when the building was shelled.

Tallis said it is highly likely that there are more ivories buried in the Iraqi soil and awaiting discovery.

The British Museum has recently put some of its collection on permanent display and intends to make others available for traveling exhibitions.

or register to post a comment.